Principles of Ocular Pain Control

Identify the cause of your patients' achy eyes and get familiar with meds that provide relief.

Release Date:

January 2016

Expiration Date:

January 1, 2019

Goal Statement:

When patients present with ocular pain in either the anterior or posterior segment, the best way to alleviate it is to follow a specific protocol, based in part on the underlying pathology. This course provides an overview of that protocol and the associated pathologies. Additionally, it reviews the use of several specific pain medications and their indications and associated risks.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Julie Tyler, OD

Credit Statement:

This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. COPE ID is 48196-OP. Please check your state licensing board to see if this approval counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Joint-Sponsorship Statement:

This continuing education course is joint-sponsored by the Pennsylvania College of Optometry.

Disclosure Statement:

Dr. Tyler has no financial relationships to disclose.

Ocular pain can occur for many reasons in a clinical care setting. Patients who tend to present most acutely—and usually with greater severity of symptoms—most often have an anterior segment finding (such as dry eye, anterior uveitis or conjunctival irregularities) or angle closure.

However, ocular pain may also be associated with a variety of conditions in the posterior segment, such as optic neuritis, ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS) and ocular complications associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA).

|

|

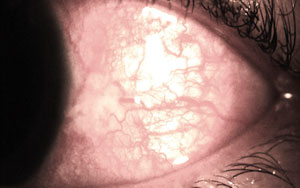

| Fig. 1. Atypical lower lid granuloma. |

This article reviews nontraumatic, noninfectious causes of ocular pain in both the anterior and posterior segments, and discusses oral and topical management.

Anterior Segment Considerations

Most anterior segment structures can be associated with pain. The cornea is especially sensitive due to its high concentration of sensory nerves, particularly in the center of the cornea—the most sensitive of all anterior segment structures. In fact, a recent study noted the cornea is the most densely innervated tissue in the body, due to its thick trunks of nerves that enter the stroma directly from the sclera, episclera and conjunctiva and send a large plexus through Bowman's membrane and just beneath the basal epithelial layer.1 Any defect involving the cornea and its array of nerves, such as a recurrent corneal erosion (RCE) or extensive ocular surface disease, can be extremely painful. These and other corneal conditions can produce pain that varies in duration. Management options to control this pain may range from mild palliative agents to strong prescription opioid medications.

Several anterior segment conditions are associated with ocular pain (Table 1). Often, patients will tolerate minor anterior segment problems until they experience corneal involvement. For example, a 43-year-old white male presented with complaints of a red, irritated right eye. He noted a lid "bump" that had changed significantly in the previous 24 hours. Within the last day, the lesion, which had been growing slowly for at least two weeks, had "flipped" and was now outside the lid, and starting to rub against the conjunctiva and cornea (Figure 1).

While the patient had noted puffiness and increasing size for approximately two weeks, the onset of discomfort and bleeding finally brought him into the clinic. His ocular history was significant for a previous history of a "stye" that had been unresolved, despite a prescription, provided elsewhere, for oral amoxicillin. His visual acuity was 20/25 OD, OS with normal preliminary test results. The anterior segment exam revealed a large, vascularized, lobed and stalked lesion with associated diffuse staining of the conjunctiva and temporal cornea. We diagnosed an atypical granuloma.

| Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Nontraumatic, Noninfectious Primary Anterior Segment Pain • Dry eye syndrome • Limbal stem cell deficiency • Anterior uveitis • Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy • Recurrent corneal erosion • Significant hypoxia/CL associated red eye • Corneal hydrops associated with keratoconus • Iatrogenic/medicomentosa-induced corneal damage • Post-surgical irregularities • Shield ulcer secondary to vernal/atopic conditions • Episcleritis (less likely) • Scleritis • Secondary angle closure • Bullous keratopathy |

A granuloma tends to be a relatively small nodular inflammatory lesion that may be triggered by infectious or noninfectious entities, such as a hordeolum or a small foreign body (e.g., sand), respectively. These localized changes most commonly develop from the palpebral conjunctival tissue and result in mild foreign body sensation. Due to the large size of this lesion, the discomfort and findings were greater than typical. To confirm the source of the patient's pain, we used a drop of proparacaine 0.5% in office. The patient experienced relief from most of his symptoms, which further confirmed the etiology; unfortunately, proparacaine has dose limitations, as it is short acting and results in an unstable epithelium when used chronically.

The patient was provided with the steroid/antibiotic combination medication Tobradex (tobramycin and dexamethasone, Alcon) QID, to reduce the inflammatory response and pain mediators within the granuloma, as well as provide protection against secondary infection.

The patient responded excellently to the management with the lesion shrinking and symptoms subsiding within 18 hours of initiation of topical therapy.

Had the patient developed a secondary anterior uveitis, a cycloplegic agent would have decreased the inflammatory response and secondary pain triggered by the normal pupillary constriction to light; the same intervention is appropriate for patients with primary uveitis.

Initial Pain Management

When managing ocular pain, follow this rule of thumb: first, treat the cause; then, adequately and effectively treat the pain.

Once a treatment regimen for the underlying condition is established, initial pain management can begin. In mild cases, this can involve using palliative measures and topical pain medications, such as cool compresses and artificial tears. If you recommend artificial tears, consider the length of anticipated patient use, necessity of clear vision, drop formulation and likelihood of pain recurrence. For patients with recurrent corneal erosion (Figure 2), recommend use of an ointment prior to bedtime to decrease the risk of overnight adherence of the most superficial layers of the cornea to other ocular surfaces. Consider an ointment that does not contain medications per se (e.g., Refresh Lacri-Lube, Allergan) or a more targeted recommendation such as hypertonic ointment (Muro 128, Bausch + Lomb). Sodium chloride drops and ointment may reduce physiologic epithelial edema and secondarily reduce the risk of painful re-erosions in the morning.

| Table 2. Review of Topical Steroids, Indications, Relative Risks |

|||

| Strong Steroids | Indications/Benefits

|

Specific Relative Risks

|

|

| Durezol (difluprednate 0.05%, Alcon) |

Strong anti-inflammatory agent; Does not need to be shaken; Dosing approximately ½ than with traditional prednisolone acetate |

Quick, significant rise in IOP; Initial cost to patient |

|

| Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate 0.5%), gel or ointment, Bausch + Lomb |

Good for chronic, recurrent inflammatory conditions; Less likely to increase IOP than other "strong steroids" |

Blur associated with instillation; Less posterior penetration |

|

| Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate 1%), Allergan and generic |

All-purpose steroid for significant inflammatory conditions such as anterior uveitis |

Generic formulation requires significant shaking |

|

| Generic prednisolone sodium phosphate 1% |

Potent, relatively inexpensive; Use for anterior surface inflammation and postoperative management |

No shaking necessary |

|

| Mild/Moderate Steroids |

Indications/Benefits

|

Specific Relative Risks |

|

| Alrex (loteprednol etabonate 0.2%), Bausch + Lomb |

Chronic allergy; Good for long-term use due to mild strength and less likely increase in IOP |

Cost to patient |

|

| Flarex (fluorometholone acetate 0.1%, Alcon); FML (Allergan) |

Mild inflammatory conditions: pingueculitis, allergy |

Some variable penetrance and limitations for management |

|

Proposed general benefits of hyperosmotic agents are demonstrated in a study on the effects of these agents on epithelial disruptions during LASIK, resulting in decreased epithelial edema—especially in patients older than 34 years.2 However, in a separate study with 26 participants, there was no difference in the occurrence of objective signs of recurrent erosion between hypertonic saline ointment vs. tetracycline ointment or lubricating ointment.3 In short, prophylactic lubrication is needed, but the exact management remains unclear for best reduction of repeat erosions.

Steroidal Agents

Both topical and oral corticosteroids can influence the inflammatory cascade early within the response and help decrease production of pain modulators. All steroids act by blocking most pain-mediating prostaglandin pathways. Steroids can be highly effective in the management of patients with uveitis, scleritis, acute dry eye symptoms and various other noninfectious ocular conditions associated with inflammation.

Common ocular side effects of steroids include increased intraocular pressure (IOP), risk of secondary infection and risk of cataract formation. Steroids may also reduce the cornea's ability to heal quickly due to reduced time for collagen formation, making topical steroids a less-than-ideal option for patients with already increased collagenase activity.

Finally, prescribing may be more complicated for steroids than some other pain modulators because dosing options and relative risk of side effects vary for different topical steroids (Table 2). Treatment regimens for different conditions can vary significantly based on the ability of a specific corticosteroid to penetrate different ocular surfaces. Each specific steroid carries its own benefits and risks of complications.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Another class of topical and oral agents for pain management, the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), work slightly further down the inflammatory cascade than steroids to decrease inflammation and diminish pain by blocking the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathways that lead primarily to prostaglandin formation.4 Some newer-generation topical NSAIDs have better penetration into the posterior chamber than older versions and require less frequent dosing, making them more effective in posterior segment penetration.5 That is why these agents continue to be used routinely and are so effective for pain following cataract surgery.

Historically, there was an 'idiosyncratic' risk of corneal melt reported in multiple case reviews with various NSAID medication formulations.6,7 Since the initial reports, various mechanisms for the corneal melt have been proposed, including an uncommon collagen disorder adversely affected by COX enzyme inhibition, activation of MMPs, or due to decreased corneal sensitivity associated with topical NSAIDs complicated in patients with dry eye and identifiable, pre-existing epitheliopathy.8 Thus, topical NSAIDs may be disruptive to patients with significant dry eye.

|

|

| Fig. 2. Sodium fluorescein staining helps diagnose recurrent corneal erosion. |

Cyclosporine

Medications that are classified as immunomodulators, such as cyclosporin-A, may be used as an adjuvant for pain management. These medications act to modify the effects of other agents by blocking several different cytokines involved in the inflammatory process; however, cyclosporin-A does not directly block pain-causing prostaglandins as effectively as do either steroids or NSAIDs. For patients with chronic dry eye associated with rheumatologic diseases, where underlying systemic inflammation contributes significantly to ocular pain, cyclosporin-A may be beneficial. Nevertheless, these patients will often only find immediate pain relief with topical steroid pulse-therapy treatment.9

Patients with severe dry eye may also find some assistance and chronic pain relief with the use of oral omega dietary supplementation.10

Case Consideration

A 54-year-old black female presented with a history of a mildly red eye for the past six months. She reported a sudden onset of concurrent increased redness and pain in the left eye for the previous three days. The patient denied additional ocular symptoms or significant ocular history. However, she had a complicated medical history that included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and rheumatoid arthritis (RA)—all for seven years. The patient was on multiple systemic medications, including lisinopril, lovastatin, meloxicam, folic acid, prednisone (5mg, QID), and methotrexate (2.5mg, BID).

Her visual acuity was 20/20-1 OD and 20/40 OS. Slit lamp findings revealed deep scleral injection and thickening 360 degrees in the left eye without blanching upon instillation of phenylephrine 2.5% (Figure 3). Blood pressure measured 132/87mm Hg with Goldmann measured IOP of 16mm Hg OD and OS. The diagnosis was diffuse non-necrotizing anterior scleritis in her left eye secondary to poorly controlled RA.

|

|

| Fig. 3. Initial presentation of scleritis in the left eye. |

Pain is a common complaint in patients with scleritis—and changes in associated systemic conditions, management protocols or both, often precede ocular flare-ups.11,12 Initial topical management (e.g., steroids) may be beneficial to quell some symptoms, but true management requires oral anti-inflammatory and pain comanagement with the rheumatologist/managing physician. In this case, the rheumatologist increased the oral prednisone from 5mg QID to 20mg QID while the patient was also prescribed topical Durezol (difluprednate, Alcon) QID OS.

One study reported that nearly 60% of scleritis patients require oral steroids or immunosuppressive agents to control the disease (oral steroids ~ 31.9%, systemic immunosuppressive agents ~ 26.1%).13

At the one-week follow-up, the patient reported overall improvement of symptoms and VA with residual, moderate scleral injection and thickening. As demonstrated in this patient, it is imperative to comanage the patient's underlying condition in cases where the patient presents with both acute pain and a contributing underlying systemic conditions for complete, long-term pain resolution.

Oral Medications

In many cases, non-prescription oral medications may be suitable to assist in pain management. For example, over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, can be quite helpful in alleviating patients' pain; at higher dosages, it may help reduce inflammation. Ibuprofen is an analgesic, antipyretic and potential anti-inflammatory. Analgesic dosing is 200mg to 400mg every four to six hours whereas an anti-inflammatory therapeutic dosing is 600mg to 800mg every six to eight hours. Ibuprofen may be used to assist in ocular surface injuries, moderate-to-severe episcleritis, mild scleritis, uveitis and postoperative cataract surgery regimens.14,15 However, ibuprofen should be recommended/prescribed with caution in women of childbearing age, as it falls into the historic FDA pregnancy category C.

Another OTC medication that may be used for pain relief is naproxen sodium, branded as Aleve, Anaprox and Naprosyn. The OTC formulation of 220mg naproxen sodium actually contains 200mg of naproxen. Normal adult dosing for the OTC formulation is 220mg every eight hours, not to exceed two caplets in any eight- to 12-hour period. As a prescription formulation, it is available in a large variety of dosing options ranging from 250mg to 750mg (once daily dosing).

Prescription NSAID medications include Mobic (meloxicam, Boehringer Ingelheim) and Celebrex (celecoxib, Pfizer). Mobic is typically used for patients with arthritis—both osteo and rheumatoid. Children older than two years who have juvenile rheumatoid arthritis may also use Mobic.16 This drug can be used daily as either 7.5mg or 15mg tablets or a 7.5 mg/5ml suspension. The NSAID celecoxib is a COX-2 inhibitor that is available in prescription formulations of 50mg, 100mg, 200mg and 400mg options. A typical adult dose is 400mg initially for pain and then 200mg every 12 hours.

NSAID Risks

While all NSAID medications may be beneficial for pain relief, they are accompanied by a variety of risks, warnings and contraindications. All NSAIDs have cardiovascular risks, including an increase propensity for myocardial infarction and stroke. Gastrointestinal risks include bleeding, ulceration and gastric or intestinal perforation. Prescription NSAIDs should be used with caution, especially in patients with congestive heart failure, hypertension, asthma, GI ulcers and renal impairment. The negative association with asthma and oral NSAID use is due to an increased risk of allergic reactions to the class of medications in patients with asthma. Additional contraindications include a potential for cross-reactivity in individuals with aspirin allergy and complications for individuals with chronic hepatitis. Also, avoid NSAID use in patients who complain of pain from coronary artery bypass graft surgery, as they may face bleeding complications. All oral NSAIDs discussed are historically pregnancy category C.

| Table 3. Differential Diagnosis of Nontraumatic, Noninfectious Posterior Segment Pain • MS/retrobulbar optic neuritis • GCA symptoms associated with CRAO, A-AION • Posterior uveitis • Posterior scleritis • HZO prodrome phase • OIS • Panuveitis |

Aspirin is the final OTC NSAID that warrants discussion for pain management. The usual dose for pain and fever in adults is 325mg to 650mg every four to six hours, with a total daily dosage that should not exceed four grams per day, with some health care practitioners recommending even less total daily. Like the other NSAID medications, aspirin is contraindicated for individuals with recent stomach or GI bleeds and allergy to the other NSAIDs because of possible cross-reactivity. However, due to the excellent blood thinning capabilities of aspirin, it is also contraindicated with concurrent Coumadin use, bleeding disorders or heavy alcohol use. Aspirin should not be used in pregnant or breastfeeding women. Finally, due to the risk of death associated with Reye's syndrome—a condition that has occurred when aspirin was used to treat flu-and cold-like symptoms in children—the FDA has recommended that aspirin and aspirin-containing products not be used to treat patients younger than 19 years.

An over-the-counter medication that is not considered an NSAID but is used to treat fever and pain is Tylenol (acetaminophen, Johnson & Johnson). While useful in the treatment of ocular pain, acetaminophen is an especially complicated pain medication to manage because it is available in so many single medication and combination formulations. A total maximum adult intake per day—including all medications containing acetaminophen, like aspirin—should not exceed four grams daily. The main contraindication for use of acetaminophen is liver damage, as it is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States.17 In 2011, the FDA asked drug manufacturers to limit the strength of acetaminophen to 325mg/tablet in prescription drug products, which are predominantly combinations of acetaminophen and opioids.18

Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma

While many topical and oral analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents may be beneficial in the management of certain types of ocular pain, understanding the etiology of an inciting event and treating the direct cause is imperative in most cases.

For example, a 68-year-old Asian female presented with severe constant pain and primarily frontal headache with concurrent blurred vision. She reported recently visiting the emergency room for headache complaints, for which she was given a diagnosis of "migraine" and provided with a prescription analgesic without relief of her symptoms. Instead, her headache got worse and she began to experience vomiting associated with the pain. She denied any ocular history prior to her visit and was not taking any ocular medications. Uncorrected visual acuity was 20/30 OD and 20/50 OS with normal ocular motility and confrontation fields but a mid-dilated pupil in her left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed grade three conjunctival injection and corneal edema with compromised views in the anterior chamber of her left eye. IOP was 24mm Hg OD and 48mm Hg OS. Gonioscopy revealed a closed angle in the left eye and peripheral anterior synechiae consistent with signs of chronic angle closure and acute angle closure at present.

The patient required multiple pressure lowering agents—both oral and topical—starting with in-office Iopidine 0.5% (apraclonidine), a beta-blocker and eventually oral acetazolamide due to the chronicity of her condition.

When ocular pain is associated with increased IOP, use of topical pressure-lowering agents is essential to start to manage the patient's symptoms. In-office Iopidine (a topical alpha-agonist), topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and a topical beta-blocker may be initiated to try to reduce aqueous production. Pilocarpine may also be effective in angle closure patients with an IOP lower than 40mm Hg—used to physically move the iris away from the angle structures; however, at higher pressures (as in the case presented) it is not effective.

In patients like the one discussed, where the condition is chronic, it is usually necessary to use oral or IV medications such as Diamox (acetazolamide, Barr) PO (2 x 250mg tablets). Upon resolution of the acute crisis and when IOP "control" is obtained, long-term management options can be discussed with the patient.

Posterior Segment/Neurological Conditions

Conditions beyond the anterior segment that may be associated with ocular pain can be acute, like optic neuritis associated with multiple sclerosis (MS), or may be dull, constant and longstanding, such as the pain associated with ocular ischemic syndrome (Table 3).

The nature of the pain is generally different than that noted in the anterior segment, which is often accompanied by a clear inciting event. The pain associated with posterior segment diseases in particular may be less acute and more difficult for the patient to localize and describe. Unlike the cornea, the retina has no pain receptors and any posterior segment pain is due to neurologic symptoms or associations, or ischemic-related disease.

A particularly challenging presentation of bilateral, persistent eye-related pain with foreign body sensation was recently described as ocular neuropathic pain that developed in a patient with vitamin B12 deficiency.19 The patient responded well with vitamin B12 therapy—which may make this a differential in cases of persistent ocular pain going forward.

Another, more common, but equally challenging, ocular-related pain occurs in the prodrome phase associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO). Patients with this neurologic condition are often in severe pain and only a detailed history and description of the location and pattern of the pain may allow for early diagnosis, as initial findings are limited. The pain associated with HZO is generally significant enough to require management with opioids.

Medications for Severe Pain

Opioid drugs may be indicated for moderate-to-severe ocular pain, but they have several contraindications and potential side effects. When considering these medications, assess the likely efficacy vs. potential side effects and choose an option that best suits the patient. This class is contraindicated in patients who have depression and severe respiratory disease, due to the likelihood of exacerbation of symptoms.

Opioids should be used with caution in patients who use alcohol chronically, have Addison's disease, renal dysfunction, a history of drug abuse, impaired lung function, psychosis, hypotension or cardiovascular disease. Side effects include itching, rash, constipation, seizures and cardiotoxicity.

Ultram (tramadol, Janssen), an opioid class medication used to manage moderate to moderate-severe pain, is available as a 50mg tablet or 100mg, 200mg or 300mg extended-release capsules. The typical adult dose is between 50mg and 100mg every four to six hours, not to exceed 400mg per day. A modification of dosage is recommended for patients with kidney or liver problems. Ultram has two mechanisms of action—a weak mu-opioid receptor agonistic effect, leading to induced serotonin, and the ability to inhibit reuptake of norepinephrine. Ultram was recently moved from a non-scheduled to a Schedule IV medication due to the clinical recognition of risk for drug addiction.

Tylenol 3 (Johnson & Johnson) is a combination of 30mg codeine with 300mg acetaminophen that is categorized as a Schedule III drug. Tylenol 4 contains a higher dosage of codeine (60mg), but is currently also listed as a Schedule III drug. Tylenol 3 is usually dosed one to two tablets every four hours. Both Tylenol 3 and Tylenol 4 may be used to manage post-surgical pain or corneal hydrops, and may be used for severe trauma, abrasions and erosions. A primary concern in patients using Tylenol 3 or Tylenol 4 is the risk of depressed respiratory function. The side effects and contraindications are typical for opioid class medications with cautions against prescribing to anyone with a hypersensitivity to narcotics or substance abuse risk.

Oxycontin (oxycodone, Purdue), a Schedule II medication, has a high potential for abuse. It is available in 5mg, 10mg, 15mg, 20mg and 30mg tablets. Additionally, it is available in other doses/formulations for extended release to decrease the risk of abuse. Generally, Oxycontin is prescribed 5mg to 30mg every four to six hours for significant pain.

A final notable pain medication is hydrocodone, which is also a Schedule II class medication. Hydrocodone is available in combination with several other products (e.g., acetaminophen, ibuprofen) with a variety of different brand names and specific indications depending on the combination. For example, hydrocodone combined with Vicodin (hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen, Abbvie) would be used for pain, whereas hydrocodone combined with guaifenesin would be indicated for cough suppression.

When patients are suffering from a painful ocular condition, they often have comorbidities that contribute to that pain. It is necessary for optometrists to look beyond the eye to consider the overall welfare and health status of the patient. For patients experiencing pain due to underlying systemic inflammation, oral steroids or methotrexate may be warranted to manage an underlying systemic condition, but these require careful comanagement. Other adjuvant medications may include muscle relaxers, anti-anxiety medications or antidepressants. Regardless, effectively managing pain is essential to the well-being and recovery of the patient. Counsel the patient about appropriate expectations and the value of communicating with their physicians—both primary care and specialists, including optometrists.

Dr. Tyler is a module chief of primary care for The Eye Care Institute at Nova Southeastern University in Davie, Fla.

1. Woreta FA, et al. Management of post-photorefractive keratectomy pain. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(6):529-35.2. Holzman A, LoVerde L, Effect of a hyperosmotic agent on epithelial disruptions during laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(5):1044-9.

3. Yamada M, Mashima Y. Three-step treatment of recurrent corneal erosion. Folia Ophthalmologica Japonica 1998;49(10):839–43.

4. Vane J, Bakhle Y, Botting R. Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:97-120.

5. Baklayan G. 24-hour evaluation of the ocular pharmacokinetics of (14) C-labeled low-concentration, modified bromfenac ophthalmic solution following topical instillation into the eyes of New Zealand white rabbits. ARVO Meeting Abstracts; May 5, 2013.54:123.

6. Prasher P, Acute corneal melt associated with topical bromfenac use. Eye Contact Lens 2012 Jul;38(4):260-2.

7. Asai T, Nakagami T, Mochizuki M, et al. Three cases of corneal melting after instillation of a new nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Cornea 2006;25(2):224 – 7.

8. Gokhale N, Vemuganti G. Diclofenac-induced acute corneal melt after collagen crosslinking for keratoconus. Cornea 2010;29:117-9.

9. Sheppard J. Guidelines for the treatment Of chronic dry eye disease. Manag. Care. 2003 Dec;12(12 Suppl): 20-25.

10. Hom M, Asbell P, Barry, B. Omegas and dry eye: More Knowledge, More Questions. Optom Vis Sci. 2015 Sep;92(9):948-56.

11. Watson P, Hayreh S. Scleritis and episcleritis. Brit J Ophthal. 1976;60:163-91.

12. de la Maza M, Moilina N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez L, et al. Clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:43-50.

13. Jabs D, Mudun A, Dunn J, Marsh M. Episcleritis and scleritis: clinical features and treatment results. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000 Oct;130(4):469-76.

14. Taben M, Langston R, Lowder C. Scleritis in a person with stiff-person syndrome. Ocul Inmmunol Inflamm. 2007;15(1):37-9.

15. Porela-Tiihonen S, Kaarniranta K, Kokki M, et al. A prospective study on postoperative pain after cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1429-35.

16. Meloxicam FDA approval: www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/020938s018,021530s006lbl.

17. Punzalan C, Barry C. Acute Liver Failure: Diagnosis and Management. J Intensive Care Med. 2015 Oct 6 (epub ahead of print).

18. Acetaminophen FDA safety statement: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm239821.htm.

19. Shetty R, Deshpande K, Ghosh A, Sethu S. Management of ocular neuropathic pain with vitamin B12 supplements: A case report. Cornea. 2015;34(10):1324-5.