|

Distinguishing Episcleritis from Scleritis in Optometric Practice

Timely and accurate differentiation between these two is essential for proper management and to prevent severe ocular and systemic complications.

By Theresa Jay, OD, Melissa Chen, OD, Timothy Shoff, OD, and Steve Njeru, OD

Jointly provided by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and the Review Education Group

Release Date: November 15, 2024

Expiration Date: November 15, 2027

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: two hours

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists interested in early and accurate differentiation between episcleritis and scleritis needed for effective management.

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, participants should be better able to:

Accurately differentiate between episcleritis and scleritis in clinical practice.

Recognize the potential systemic associations of episcleritis and scleritis.

Use appropriate diagnostic techniques to accurately identify these conditions.

Employ effective management strategies for both episcleritis and scleritis.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: PIM requires faculty, planners and others in control of educational content to disclose all their financial relationships with ineligible companies. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted and mitigated according to PIM policy. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high-quality, accredited CE activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in health care and not a specific proprietary business interest of an ineligible company.

Those involved reported the following relevant financial relationships with ineligible entities related to the educational content of this CE activity: Faculty - Drs. Jay, Chen, Shoff and Njeru have no financial disclosures. Planners and Editorial Staff - PIM has nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group has nothing to disclose.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by PIM and the Review Education Group. PIM is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education and the American Nurses Credentialing Center to provide CE for the healthcare team. PIM is accredited by COPE to provide CE to optometrists.

Credit Statement: This course is COPE-approved for two hours of CE credit. Activity #129576 and course ID 94746-GO. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use: This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. The planners of this activity do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of the planners. Refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications and warnings.

Disclaimer: Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patient’s condition(s) and possible contraindications and/or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

Episcleritis and scleritis are ocular conditions that may present with similar signs but have distinctly different visual outcomes and symptoms. While episcleritis is typically a self-limiting condition with a good prognosis, scleritis is more severe, can lead to significant visual complications and is often associated with an underlying systemic disease. Hence, a slit lamp examination is essential for identifying key signs and vision threatening ocular complications. Furthermore, thorough review of systems and medical history is necessary to rule out any underlying systemic diseases. This article will explore how to differentiate the types of episcleritis and scleritis, explore the etiologies of scleral inflammation and provide guidance on management and treatment strategies for optimal patient care.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Episcleritis predominantly affects young to middle-aged females, with women being approximately three times more likely to develop the condition than men.1-2 It is rarely diagnosed in children. The episclera is located beneath the conjunctiva and Tenon’s capsule. This layer is composed of fibroblasts, collagen bundles and a fairly dense vascular network, which includes both superficial and deep vessels.2

Episcleritis is characterized by non-granulomatous inflammation of the episcleral vascular network that leads to edema and dilation of the radially oriented superficial blood vessels in the episclera. The pathophysiology involves activation of immune cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages. This activation triggers an inflammatory cascade, leading to the release of inflammatory mediators. These mediators cause vasodilation, increased vascular permeability and the migration of white blood cells into the affected area.

|

|

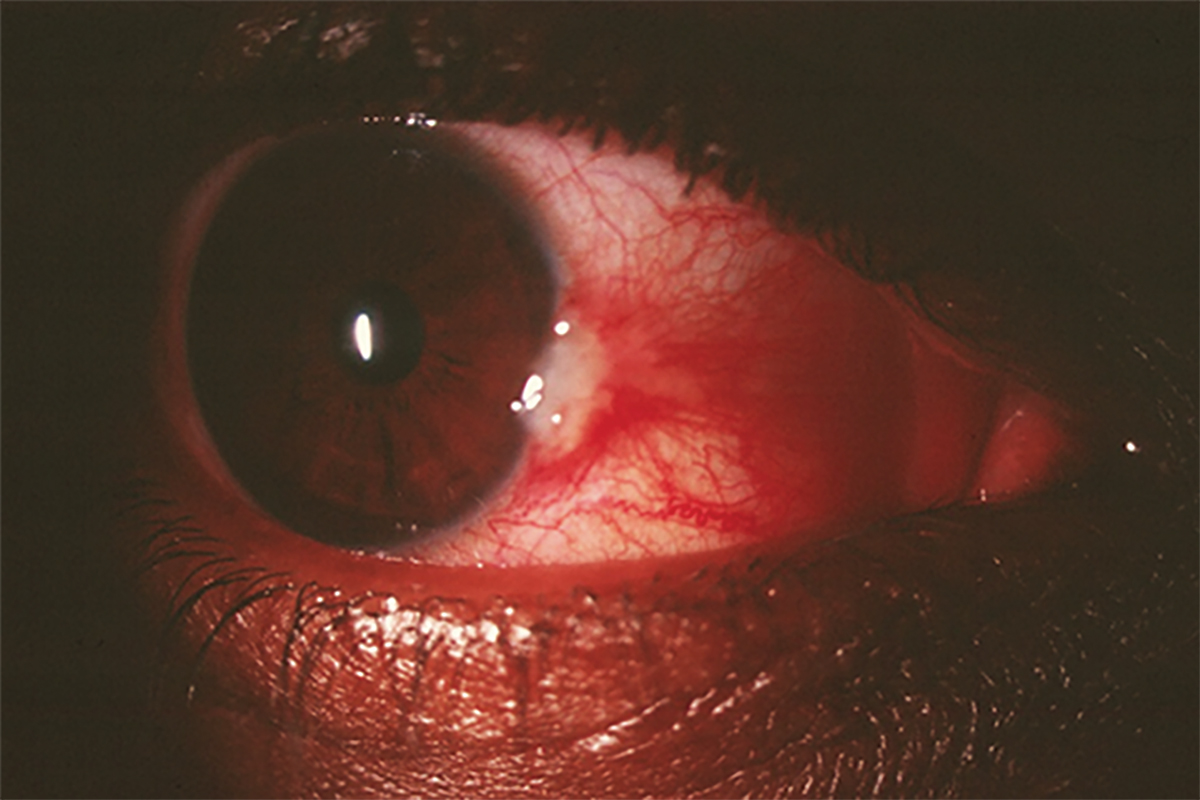

Fig. 1. Pingueculitis can often be mistaken for nodular episcleritis or scleritis. Photo: Andrew S. Gurwood, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The resulting inflammation manifests as redness and discomfort, but the condition is usually self-limiting, resolving within two to 21 days.1 Approximately two-thirds of episcleritis cases are idiopathic. However, in about 26% to 36% of cases, episcleritis is associated with an underlying systemic autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus or inflammatory bowel disease.2

Scleritis is a severe and potentially sight-threatening inflammatory condition that affects the sclera, the dense, fibrous outer layer of the eye. It is estimated to occur in approximately 10,500 cases annually in the United States.3 It predominantly affects individuals between the ages of 47 and 60 years old.3 Women are more frequently affected than men, comprising 60% to 74% of scleritis cases.3

The sclera is composed of fibroblasts and thicker collagen bundles compared to the episclera. It lacks its own blood vessels, so it is supplied by the choroid and the deep episcleral vascular plexus. During the inflammatory process in scleritis, activation of the complement system increases the recruitment of macrophages and T cells, leading to swelling and inflammation that involves both the deep and superficial vascular plexuses.1 Scleritis can be idiopathic, but it is often associated with underlying conditions such as malignancies, autoimmune diseases and side effects from certain medications.

In approximately 4% to 10% of cases, infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites are responsible for causing infectious scleritis.3 Scleritis often is associated with an underlying systemic condition. Approximately 50% of scleritis cases involve an autoimmune condition, with rheumatoid arthritis being the most common.3 One study evaluated the relationship between an associated systemic disorder and scleritis and found that 14% of patients had their conditions diagnosed due to their initial scleritis evaluation.4

Recognizing Differentials

Making the distinction between other ocular conditions is essential for preventing vision-threatening complications and ensuring appropriate and timely treatment. A thorough clinical examination and, in some cases, additional diagnostic testing are needed to guide management and prevent misdiagnosis.

Other conditions to consider include allergic or infectious conjunctivitis, which may present with similar signs. Allergic conjunctivitis is associated with symptoms of itching and presents with diffuse conjunctival injection, along with papillary or follicular reactions.5 Mucoid discharge is typical of allergic conjunctivitis, whereas purulent discharge is seen in bacterial conjunctivitis. Viral conjunctivitis presents with a diffusely red eye with watery discharge, follicular conjunctival reaction and preauricular lymphadenopathy.5

|

|

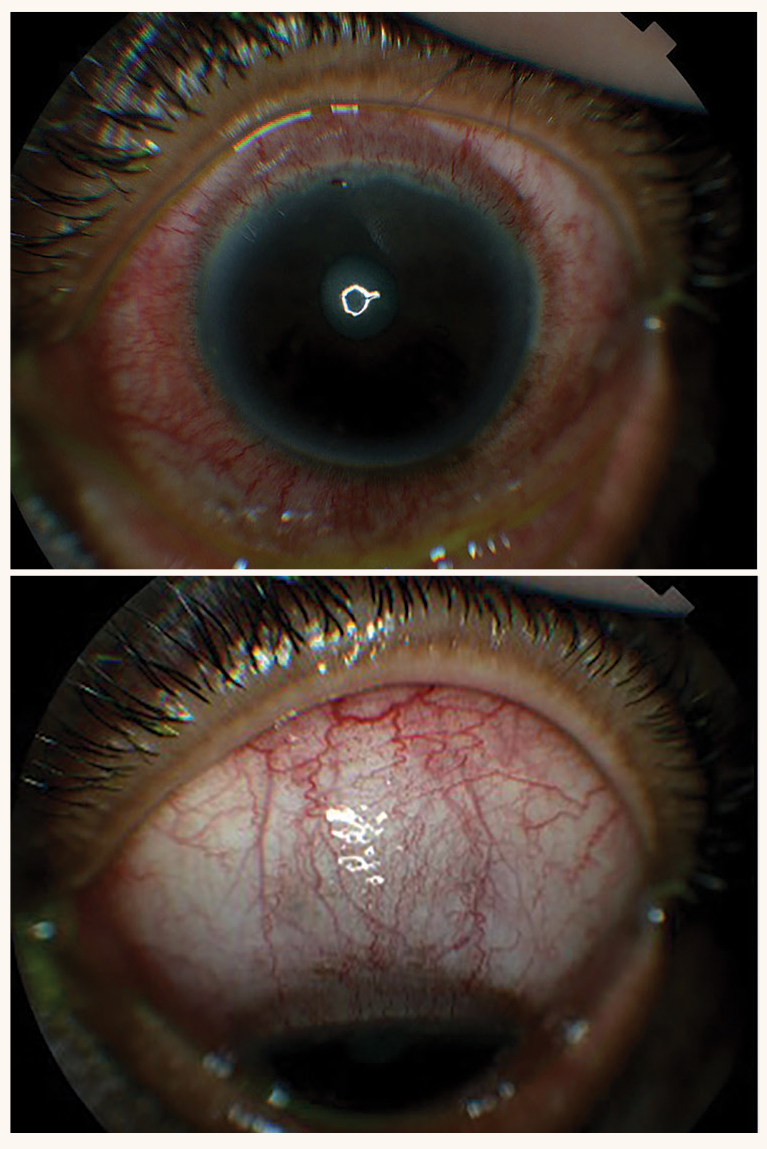

Fig. 2. Idiopathic orbital inflammation, a condition that may be commonly misdiagnosed as scleritis due to the pronounced deep bulbar injection. Click image to enlarge. |

Another differential is pingueculitis, an inflamed pinguecula, which presents with sectoral injection, foreign body sensation and mild discomfort or pain (Figure 1).6 This benign condition is localized to the conjunctiva and often triggered by environmental factors like air or UV exposure. The inflamed pinguecula can be easily manipulated with a cotton swab to differentiate it from deeper inflammation.5

Anterior uveitis is another important differential diagnosis, particularly in patients presenting with pain, photophobia, decreased vision and redness. Signs of uveitis include normal to decreased vision, anterior chamber cell and flare and keratic precipitates (fine or mutton-fat).6 A hallmark of iritis is circumferential limbal injection, also known as ciliary flush. In severe cases, posterior synechiae may form, and intraocular pressure may become elevated.6 Anterior uveitis can be associated with scleritis in up to 40% of cases due to spillover inflammation from the scleritis, rather than primary involvement from the uveal tract.7

Idiopathic orbital inflammation, also known as orbital pseudotumor, can also cause an acute red eye (Figure 2). It typically presents with acute onset of orbital pain, decreased vision, diplopia and proptosis. Patients may also have tenderness in the orbital region, eyelid edema, erythema, lacrimal gland enlargement and pain with extraocular movements. Other signs may include conjunctival chemosis and elevated intraocular pressure.7

Orbital cellulitis is an urgent differential diagnosis, as it must be ruled out in patients who present with orbital pain, proptosis and decreased vision. Patients with orbital cellulitis may present with fever, eyelid swelling, pain, diplopia and decreased visual acuity. Clinical signs include proptosis, restricted extraocular movements, lid edema, erythema, an afferent pupillary defect, conjunctival injection and chemosis.6 Severe cases may lead to abscess formation or intracranial extension as well.6

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is another differential worth considering. TED can present with a variety of symptoms, including redness, tearing, foreign body sensation, diplopia and proptosis. Clinical signs may include eyelid retraction, Von Graefe’s sign (lid lag), ocular edema, epithelial defects and conjunctival injection. Orbital edema may lead to extraocular muscle restriction. Optic nerve involvement can reduce visual acuity and color vision, constrict visual fields and may also cause an afferent pupillary defect.6

|

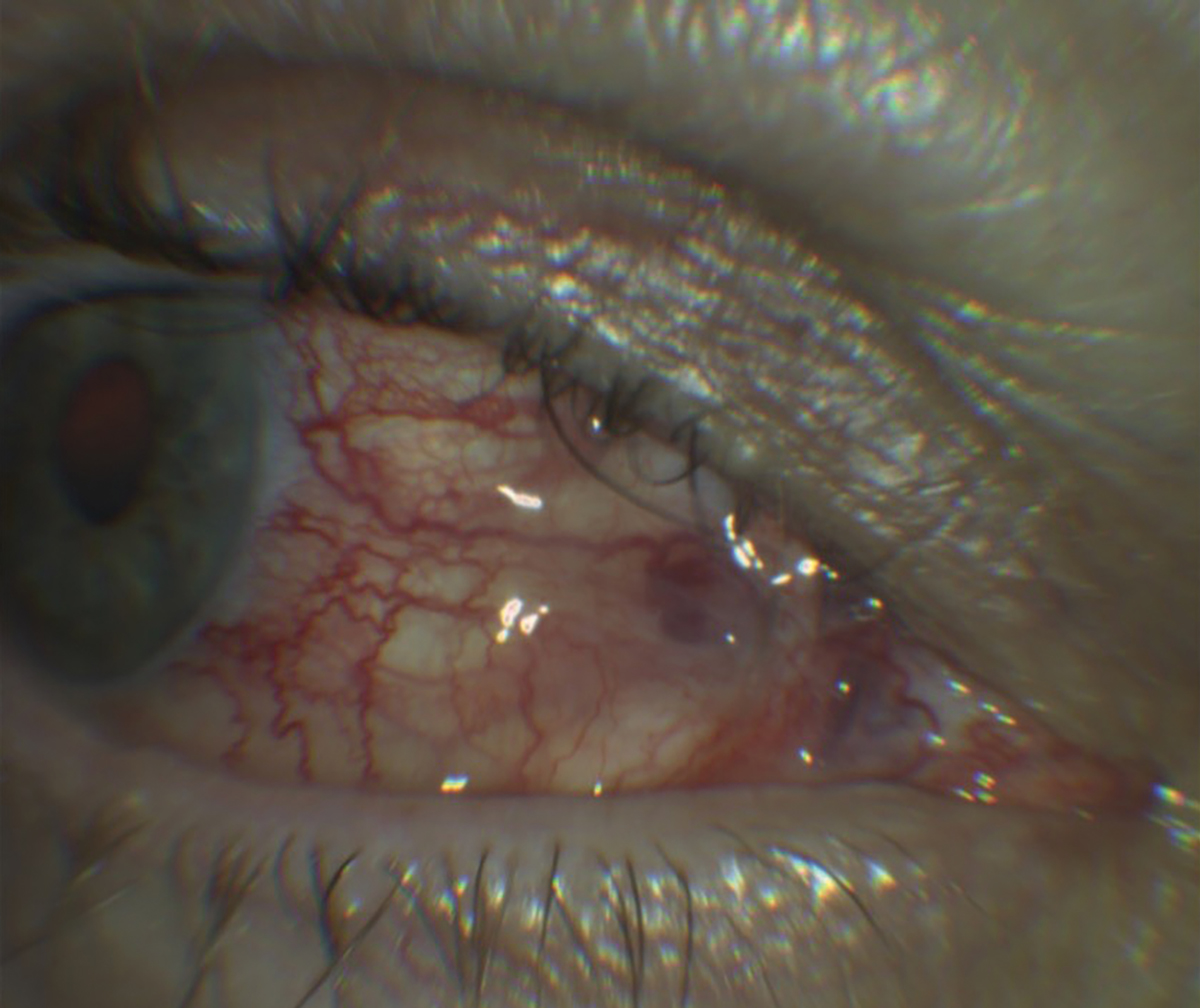

| Click table to enlarge. |

A cavernous sinus fistula can also present with red eyes. The classic triad of symptoms includes conjunctival chemosis, exophthalmos and a swooshing sound (ocular bruit). While often associated with closed head trauma, a cavernous sinus fistula can occur without it. Ocular signs include pulsatile proptosis, chemosis, increased intraocular pressure and congested ocular vasculature.6

Clinical Presentations

Episcleritis is an acute unilateral or bilateral inflammation of the episclera with symptoms of redness, mild ocular discomfort or pain and normal visual acuity. Signs include conjunctival chemosis and sectoral conjunctival injection that blanches with the application of 2.5% or 10% phenylephrine to indicate superficial vessel involvement.2 There are two classification categories: nodular and simple. Nodular is characterized by a localized elevated area of inflamed episcleral tissue with vascular injection. Simple episcleritis presents with episcleral vascular congestion in the absence of an elevated nodule. Both forms are benign and relatively common, with a self-limited course.2

Scleritis, on the other hand, is an acute unilateral or bilateral inflammation of the scleral tissue with presenting symptoms of dull, persistent pain that may radiate to within the ophthalmic distribution of the trigeminal nerve.3 This is due to referred pain from the branches of the trigeminal nerve that are passing through the inflamed scleral. Additional symptoms include photophobia, swelling, redness and decreased vision. Unlike episcleritis, scleritis can also involve deeper structures of the eye, and signs include conjunctival injection with a blue or purple hue of the sclera due to scleral thinning, chemosis, globe tenderness upon palpation, anterior chamber cell and flare.3 The use of 10% phenylephrine may be helpful in determining that severity of anterior inflammation and involvement of deep episcleral vessels. Location categorization is defined by whether scleral inflammation is present either anterior or posterior to the extraocular recti muscles.3

|

|

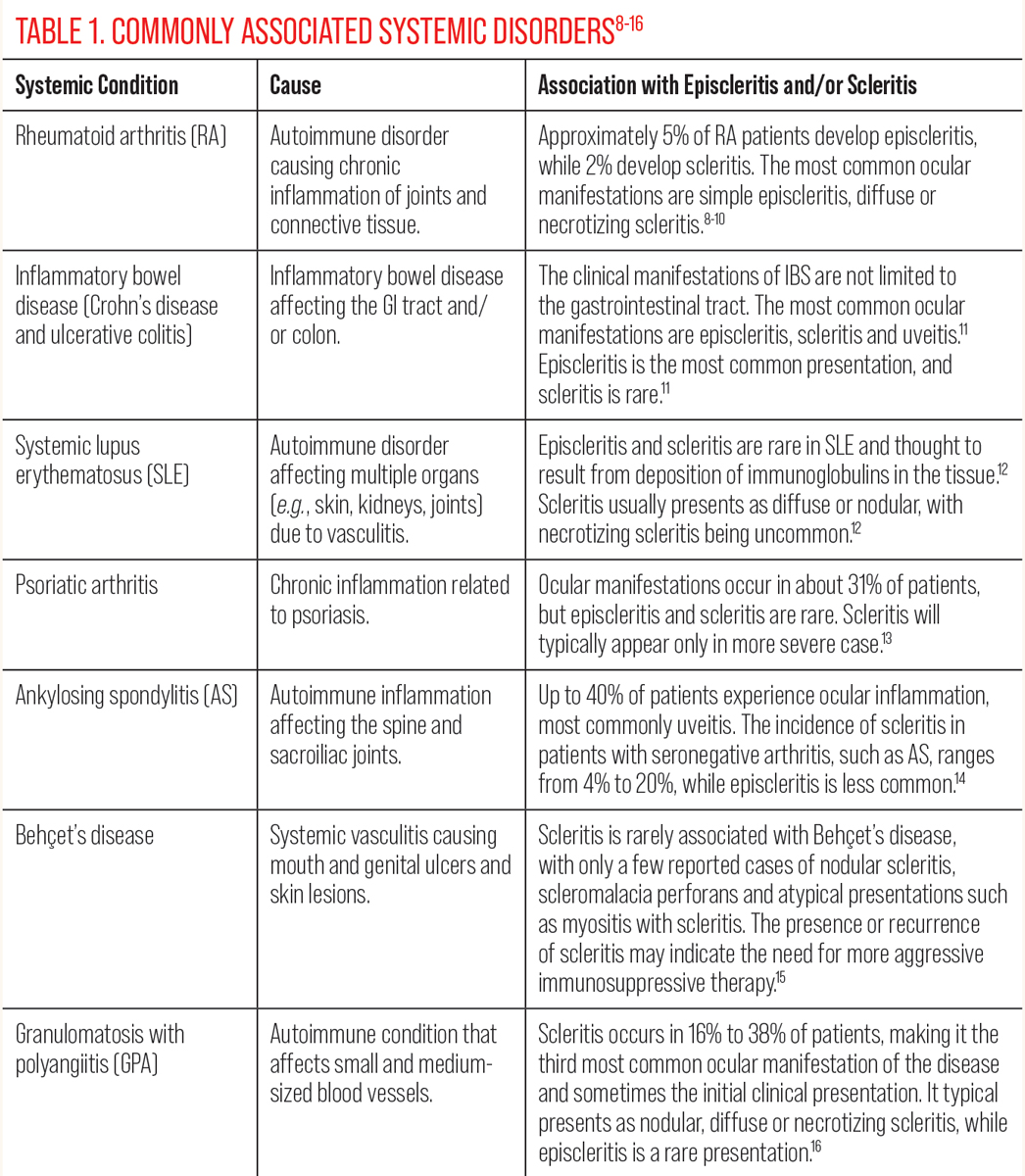

Fig. 3. These photos show an example of diffuse non-necrotizing anterior scleritis. Click image to enlarge. |

Anterior scleritis is the most common form, subdivided into diffuse, nodular or necrotizing categories (Figure 3). Diffuse scleritis may present with entire or sectoral anterior scleral edema with deep episcleral vessel engorgement. Nodular scleritis may present with a single or multiple, isolated distinct nodules of scleral edema. In the third category, necrotizing anterior scleritis is the most severe form and is characterized by significant scleral pain and tenderness. Severe vasculitis and necrosis with choroidal exposure or staphyloma may occur.3

Uncommonly, scleromalacia perforans may occur and present as necrotizing scleritis with white, avascular and painless thinning of the sclera. Posterior scleritis is inflammation located posterior to the extraocular recti muscles and can present with vision loss, pain with eye movement, serous retinal detachment or choroidal folds.3 A dilated fundus examination is essential to rule out posterior scleritis.

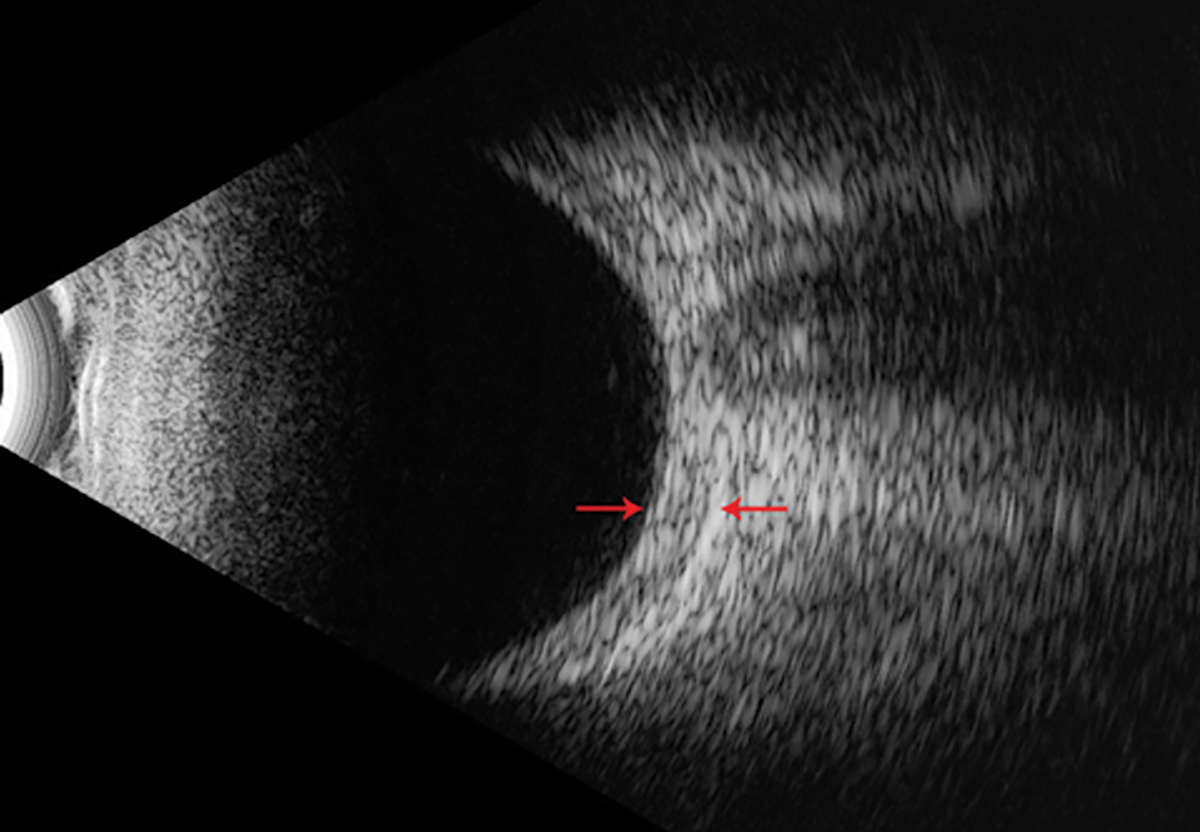

While clinical signs (e.g., redness, pain) provide diagnostic clues, imaging techniques such as B-scan ultrasonography and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) offer additional ways to determine severity and anatomical changes.

In scleritis, a B-scan shows features such as increased scleral thickness, episcleral fluid collections and presence of a choroidal detachment (Figure 4). A hallmark finding in posterior scleritis is the “T-sign.” This sign is caused by thickening of the sclera and choroid from fluid accumulation under Tenon’s capsule.3 A B-scan is especially helpful when the view of the anterior segment is obscured by media opacities like corneal or lens changes, enabling clinicians to accurately determine the presence of posterior scleritis. However, it is less effective at capturing fine details of the anterior segment compared with AS-OCT.

In contrast, AS-OCT is able to provide high-resolution images of the anterior ocular structures, such as the sclera and episclera. It offers precise measurements of tissue thickness and can differentiate between superficial inflammation (episcleritis) and deeper inflammation (scleritis). AS-OCT can also detect vascular changes and monitor the response to anti-inflammatory therapy over time. Its non-contact nature makes it an ideal tool for patients experiencing severe ocular pain. However, its limited depth of penetration restricts its use for posterior scleritis. B-scan and AS-OCT can provide complementary information in the diagnosis and management of scleritis.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Common Etiologies

Differentiating between episcleritis and scleritis is critical for patient management and outcomes. While most episcleritis cases are idiopathic, some patients may have an underlying systemic disorder, which can be infectious or noninfectious.2

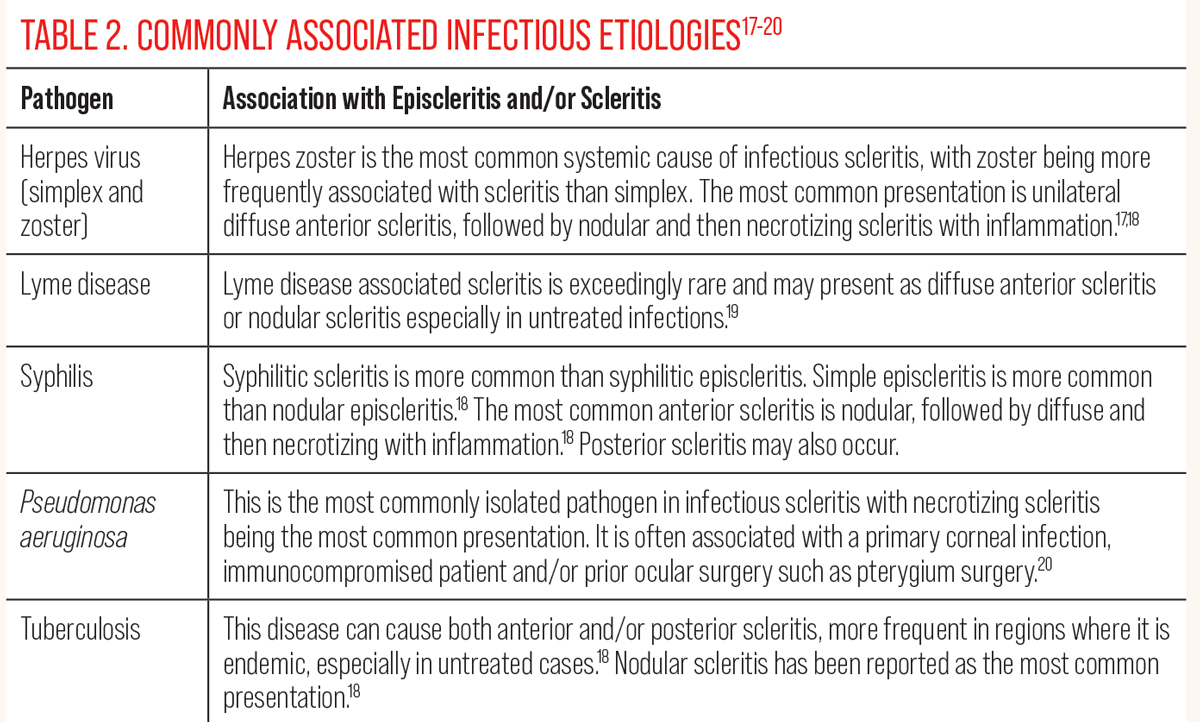

Unlike episcleritis, scleritis has a higher association with both infectious and noninfectious etiologies. Tables 1 and 2 outline noninfectious and infectious causes linked to episcleritis and scleritis, respectively.8-20

Other scleritis etiologies can include malignancy (induce inflammation mimicking scleritis), pharmacological (bisphosphonates and immune checkpoint inhibitors) and surgically induced (pterygium removal and scleral buckle procedures).3 Viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites may also lead to infectious scleritis presentations and have been reported to occur in up to 10% of all scleritis cases.3

Episcleritis Treatment and Management

Prompt distinction between episcleritis and scleritis is necessary to provide patients with proper treatment and management options, prognosis and predicting potential systemic or ocular complications. While episcleritis is generally benign and self-limiting in many cases, timely and accurate management can still alleviate symptoms and prevent unnecessary discomfort.

In most cases, artificial tears are sufficient for mild cases of episcleritis. For more symptomatic patients, topical corticosteroids such as fluorometholone 0.1% (FML), administered four times daily, have been shown to provide relief in 50% of cases.23 If fluorometholone is ineffective, prednisolone acetate 1% may be used as an alternative, offering stronger anti-inflammatory effects.21

|

|

Fig. 4. An example of a B-scan with a thickened posterior sclera without a hallmark “T-sign” as noted by the red arrows. Photo: Jim Williamson, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

However, despite the common use of topical NSAIDs in clinical practice, studies indicate that these medications offer no better relief than artificial tears in the treatment of episcleritis.22 For patients with persistent or more severe symptoms, oral NSAIDs or cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors should be considered if poor relief with topical corticosteroids. Indomethacin, a non-selective COX inhibitor, can be administered at 25mg four times daily, with the dosage reduced to 25mg three times daily after achieving a favorable response.23-24 Other oral NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, may also be considered depending on patient tolerance and response.

Scleritis Treatment and Management

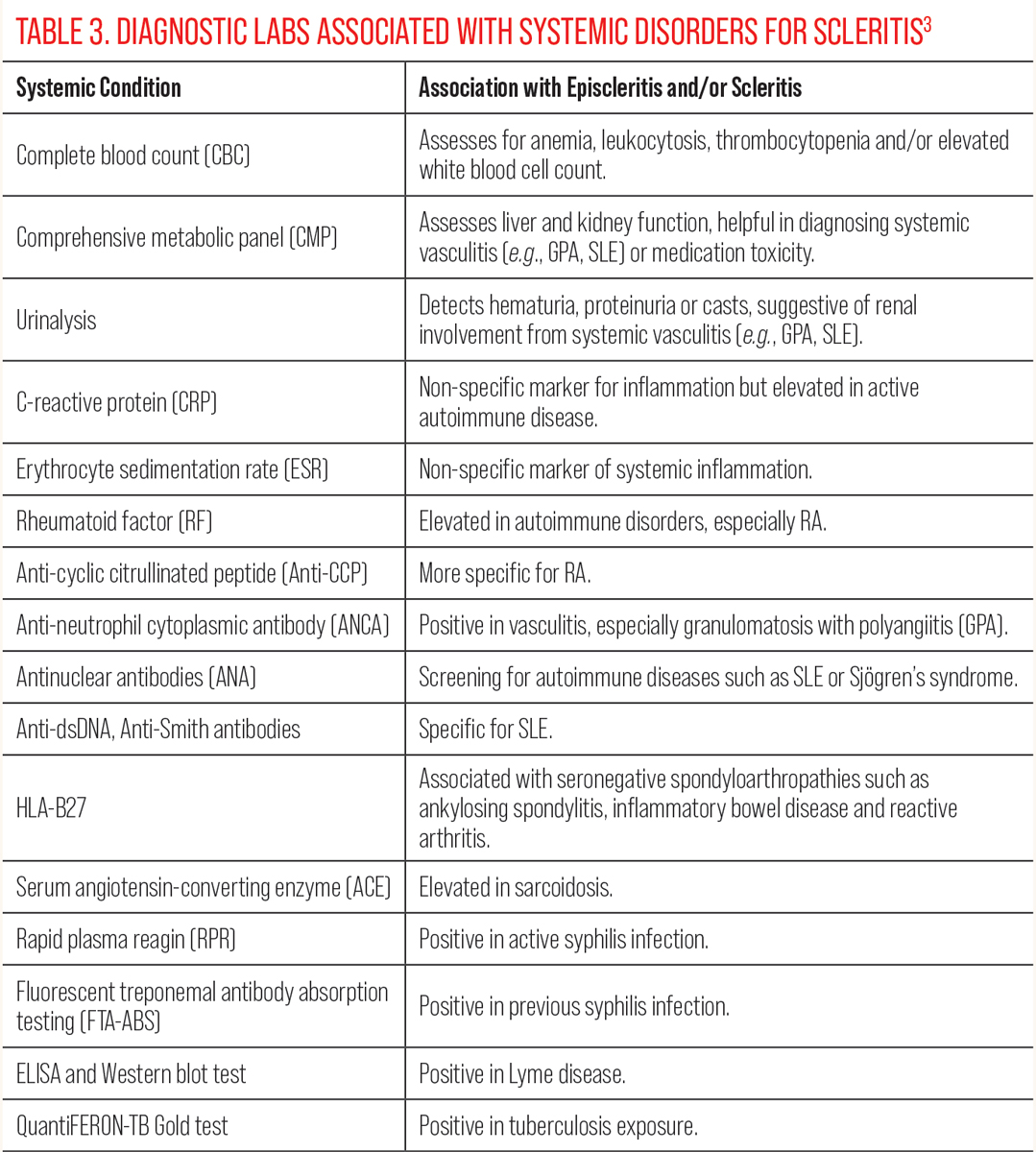

This remains a therapeutic challenge and requires a careful evaluation to ensure appropriate management. It is prudent to investigate any potential infectious causes of scleritis, as it requires targeted treatment depending on the specific pathogen, such as herpes zoster (viral) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (bacterial).3 Cases that are resistant to standard therapy should prompt a thorough reassessment for noninfectious and infectious etiologies, as misdiagnosis can result in suboptimal outcomes and potential complications. Table 3 lists recommended diagnostic labs to consider when investigating an underlying etiology for scleritis.3

Milder cases often respond well to NSAIDs, followed by steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (SAIDs) for more severe inflammation. Immunomodulatory therapy or biologic response modifiers (BRMs) are reserved for patients with refractory disease or more aggressive forms of scleritis.25 Diffuse or nodular scleritis with low levels of inflammation frequently responds well to NSAIDs such as ibuprofen (600mg to 800mg TID to QID), indomethacin (25mg to 50mg TID to QID), naproxen (250mg to 500mg BID) or celecoxib (100mg to 200mg BID).26

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

For patients with higher degrees of inflammation, corticosteroids, such as oral prednisolone (1.0mg/kg or 40mg to 60mg), may be initiated and tapered as symptoms improve.23 If there is poor response to corticosteroids after one month, or if the patient has underlying systemic disease or necrotizing scleritis, immunomodulatory therapy is indicated. Some of these agents, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil or leflunomide, are antimetabolites and commonly employed as steroid-sparing alternatives.

In severe cases, alkylating agents such as chlorambucil or cyclophosphamide may be considered, while T-cell inhibitors such as cyclosporine A, tacrolimus and sirolimus are additional therapeutic options.25 Methotrexate, favored for its balance of efficacy and safety, is the most widely used antimetabolite in these cases.25,27 For patients with refractory disease despite antimetabolites, biologic response modifiers may be used. BRMs such as infliximab, adalimumab and certolizumab (anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents) or rituximab (anti-CD20 agent) have shown efficacy in severe scleritis, although their high cost and significant side effect profiles limit their use to cases that fail to respond to other therapies.25

Local treatments, such as subconjunctival or sub-Tenon’s corticosteroid injections, for non-necrotizing, noninfectious scleritis are an effective and alternative method to systemic steroids.26 The local administration helps to reduce the risks associated with long-term systemic steroid use, such as hyperglycemia, psychosis and osteoporosis.24 However, local administration also carries the risk of ocular hypertension, cataract formation, subconjunctival hemorrhages and scleral perforation.24 It should not be used in cases of necrotizing scleritis or if there is any evidence of scleromalacia perforans.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Takeaways

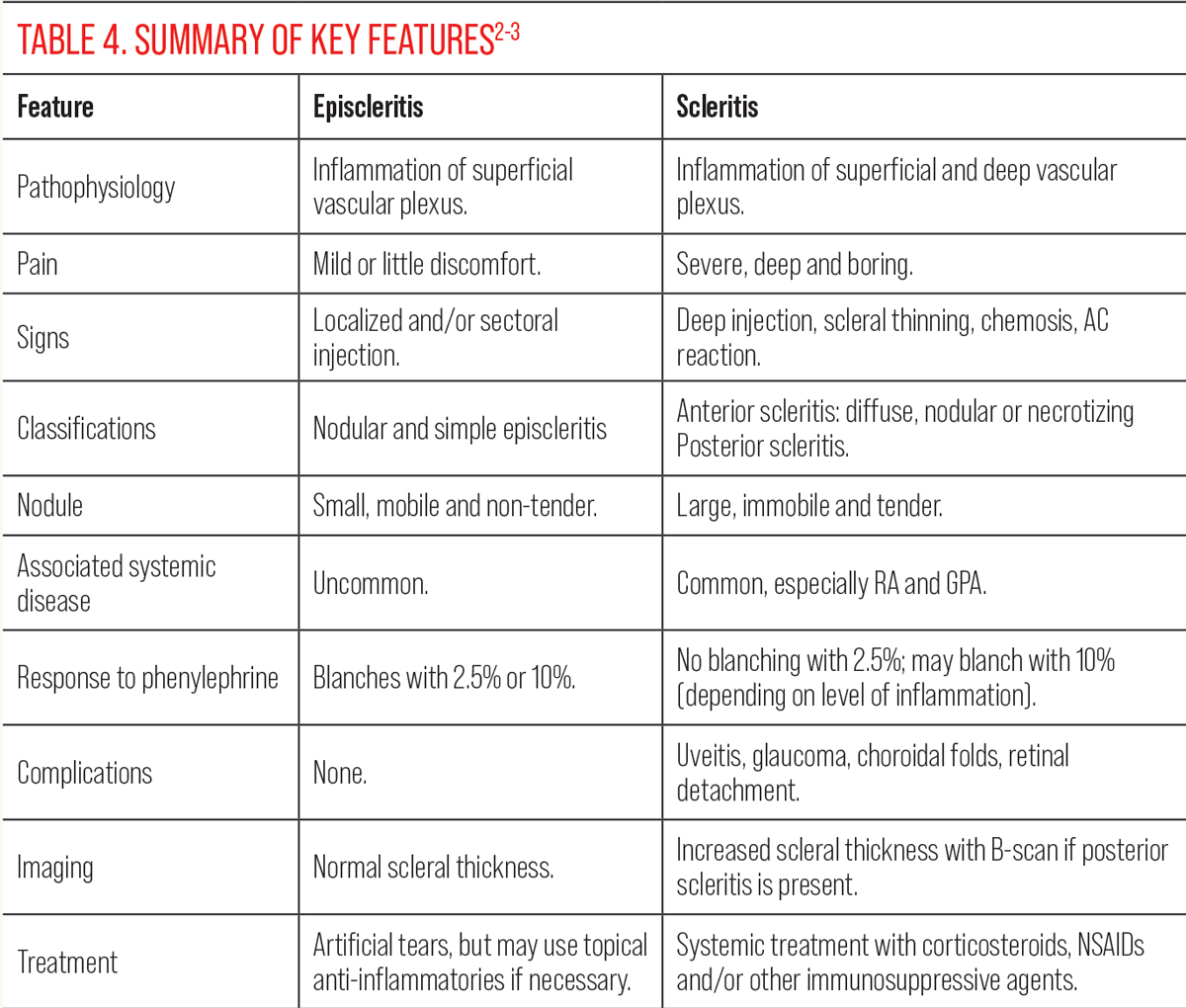

Episcleritis and scleritis are ocular inflammatory conditions that may appear to be similar but differ significantly in their pathophysiology and management. Table 4 highlights the key distinguishing features of these two conditions.2-3 Episcleritis is a benign inflammation of the episclera, whereas scleritis is a more serious, sight-threatening condition, as there is severe inflammation of the sclera, often linked to a systemic disease. Treatment for episcleritis focuses on symptomatic relief using artificial tears, and, in some cases, topical anti-inflammatories may be used to reduce discomfort. Management for scleritis requires a more aggressive approach, often including systemic NSAIDs, corticosteroids or immunomodulatory therapy to control the inflammation and prevent complications such as scleral thinning, perforation or vision loss.

Early and accurate differentiation between episcleritis and scleritis is needed for effective management and to prevent serious ocular and systemic complications.

1. Tappeiner C, Walscheid K, Heiligenhaus A. Diagnose und therapie der episkleritis und skleritis [Diagnosis and treatment of episcleritis and scleritis]. Ophthalmologe. 2016;113(9):797-810. 2. Schonberg S, Stokkermans TJ. Episcleritis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534796. Last updated August 7, 2023. Accessed October 21, 2024. 3. Lagina A, Ramphul K. Scleritis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499944/. Last updated June 26, 2023. Accessed October 21, 2024. 4. Akpek EK, Thorne JE, Qazi FA, et al. Evaluation of patients with scleritis for systemic disease. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(3):501-6. 5. Rapuano CJ. Cornea: Color atlas and synopsis of Clinical Ophthalmology: Wills Eye Hospital. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW); 2019. 6. Friedman NJ, Kaiser PK, Pineda R. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. Elsevier; 2021. 7. Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS, Jabbur NS. Scleritis-associted uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(1):58-63. 8. Artifoni M, Rothschild PR, Brézin A, et al. Ocular inflammatory diseases associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(2):108-16. 9. Promelle V, Goeb V, Gueudry J. Rheumatoid arthritis associated episcleritis and scleritis: an update on treatment perspectives. J Clin Med. 2021;10(10):2118. 10. McGavin DD, Williamson J, Forrester JV, et al. Episcleritis and scleritis. a study of their clinical manifestations and association with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60(3):192-226. 11. Troncoso LL, Biancardi AL, de Moraes HV Jr, Zaltman C. Ophthalmic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(32):5836-48. 12. Musa M, Chukwuyem E, Ojo OM, et al. Unveiling ocular manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Med. 2024;13(4):1047. 13. Amer R, Levinger N. Psoriasis-associated progressive necrotizing posterior scleritis: A six-year follow-up. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;30(3):NP7-10. 14. Murray PI, Rauz S. The eye and inflammatory rheumatic diseases: the eye and rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30(5):802-25. 15. Damodaran K, Majumder PD, Biswas J. Nodular scleritis as the eye manifestation in Behçet’s syndrome. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2015;8(1):54-5. 16. Sfiniadaki E, Tsiara I, Theodossiadis P, Chatzziralli I. Ocular manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a review of the literature. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(2):227-34. 17. Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Molina-Prat N, Doctor P, et al. Clinical features and presentation of infectious scleritis from herpes viruses: a report of 35 cases. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1460-4. 18. Shields MK, Furtado JM, Lake SR, Smith JR. Syphilitic scleritis and episcleritis: a review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2024;13(3):100073. 19. Berkenstock MK, Long K, Miller JB, et al. Scleritis in lyme disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;241:139-44. 20. Ahmad S, Lopez M, Attala M, et al. Interventions and outcomes in patients with infectious Pseudomonas scleritis: a 10-year perspective. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(3):499-506. 21. Jabs DA, Mudun A, Dunn JP, Marsh MJ. Episcleritis and scleritis: clinical features and treatment results. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):469-76. 22. Williams CP, Browning AC, Sleep TJ, et al. A randomised, double-blind trial of topical ketorolac vs. artificial tears for the treatment of episcleritis. Eye (Lond). 2005;19(7):739-42. 23. Daniel Diaz J, Sobol EK, Gritz DC. Treatment and management of scleral disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(6):702-17. 24. Watson PG, Hayreh SS. Scleritis and episcleritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60(3):163-91. 25. Sainz de la Maza M, Molina N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, et al. Scleritis therapy. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(1):51-8. 26. Beardsley RM, Suhler EB, Rosenbaum JT, Lin P. Pharmacotherapy of scleritis: current paradigms and future directions. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14(4):411-24. 27. Rachitskaya A, Mandelcorn ED, Albini TA. An update on the cause and treatment of scleritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(6):463-7. |