Optometry Today and TomorrowFollow the links below to read the other articles: Expanding Scope of Practice: Lessons and Leverage |

Information technology has put medical tools and knowledge in the hands of the public in ways that allow for greater autonomy in healthcare, and the results are decidedly mixed. The current generation is more inquisitive and health-conscious, prioritizing medical care more than the previous ones. This trend could help steer behaviors toward health-promoting habits. But the assimilation of online services into the norms of daily life drives a culture that values convenience, and, in so doing, paints in-person medical care as tedium to be avoided.

Remote refraction services and other self-administered device-based systems are the most obvious example. Understandably, these irk optometrists. But, experts say, it’s short-sighted to equate online refraction with the totality of telehealth, a sprawling field that encompasses, in essence, any digital-based delivery of medical care, education or communication—from EHR to AI and everything in between.

Online fulfillment of contact lens orders certainly fares no better. Abuse in this sector disparages clinical care and commodifies medical devices, leaving patients with misperceptions and bad habits that optometrists labor to correct.

Can telehealth’s virtues be protected from unsavory forces that don’t necessarily have optometrists’ best interest at heart? The battle over remote refraction is an early and defining test of optometry’s appetite for bringing technology into the doctor-patient relationship.

|

Online refraction, prescription renewal and other retail services continue to draw patients away from cautious practioners. Left to right: SimpleContacts, Prescription Check and Opternative. |

Troubled Beginnings

Optometry soured on telemedicine before the nascent field even had a chance. It’s easy to see why. The 2015 launch of Opternative—its brazen name flouting the role of the optometrist—was a warning shot across the bow. Why view it as anything other than a threat to their patients and their practices?

The past year has been an eventful one for Opternative. Last October, the FDA advised it to cease activities because its app constitutes a medical device, which requires regulatory medical device clearance. Continued marketing is said to violate the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.1

In May, the California Optometric Association asked the state’s attorney general to take action against self-administered vision tests that come with significant safety concerns; it also urged investigation into the joint venture of Opternative and 1-800-Contacts.2

In July, Opternative began international expansion, starting in Mexico, with Australia, Canada, Germany, South Africa and the UK also planned.3

In August, the online eye test provider also fanned the flames when it listed ODs on its “Find a Doctor” website without their consent. Concerned doctors reached out to the American Optometric Association (AOA), worried that this would imply an affiliation with Opternative.4 The company stated that if it were unable to service a patient because of ineligibility, the locator website could guide that patient to a doctor in their area.

Other entrants into the field also sideline optometrists by marketing directly to consumers or opticians. Among the former are Simple Contacts for contact lens sales and Warby Parker’s Prescription Check, an app that directs customers to its mail order eyeglass business. Among the latter, Smart Vision Labs targets optical shops with inducements of increased eyeglass sales through in-store refractions remotely verified by a doctor, while 2020Now also adds diagnostic tests run by techs with a doctor available remotely to review results. Yet more players offering variations on the theme include EyeQue, EyeNetra, GlassesOn, Pupil and MyVisionPod.

Proponents say remote vision testing reminds the public of the importance of good vision and expand access to screenings. Detractors worry they diminish the value of in-person eye exams and the importance of eye health.

Defining TermsThe World Health Organization defines telemedicine as using information technology to deliver health care services for diagnosis, treatment and prevention and for research and continuing education, particularly when geographical barriers are an obstacle to traditional methods.1 If the defining feature of telemedicine is provision of care, the concept of telehealth goes further, including all telemedicine efforts plus administrative concerns like appointment booking, electronic health records, online training and much more. An AOA position statement categorizes telehealth as follows:2 Live interactive eye and vision telehealth services use videoconferencing as a core technology. Participants are separated by distance but interact in real-time. Store-and-forward eye and vision telehealth services refers to methods of providing asynchronous consultations to referring providers or patients. Eye and vision remote patient monitoring services refer to personal health and medical data collected from an individual in one location via electronic communication, which is then transmitted to a provider in a different location for use in care coordination and related support. The AOA also states that direct-to-patient applications, including online vision tests and other mobile eye and vision-related applications, must also comply with their requirements for high quality care.

|

Can ODs Regain Control?

As new companies emerge and continue to compete for people’s attention online, the efforts to regulate online medical devices have reached certain milestones.

In April 2018, Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin signed the Consumer Protection in Eye Care Act, which allowed telehealth and online eye exams in the state and established provisions to ensure appropriate use. The law requires all patients be at least 18 and complete an in-person eye exam at least once every two years. Technology cannot be used for an initial contact lens Rx.5

These safeguards are a start, but are they enough? How do optometrists currently feel as the technology develops and patients become curious about the different services marketed to help direct their healthcare management?

A study conducted in 2017 by Jobson Optical Research found that 66% of optometrists cite online sales and exams as the biggest threat to an optometric practice; alarmingly, it also found that 54% of ODs say that they do not have the tools to prepare them to meet the challenge of remote eye exams.6 Most ODs in the survey viewed eye exams as a prime factor in growing their practices as a business. Naturally, they also viewed online sales of optical goods and online eye exams as major challenges to practice success.

Brian Chou, OD, of San Diego, believes the trend currently appeals to those with a strong self-directed mentality. However, he says as technology improves and gains greater acceptance, it will expand to the masses. This may leave patients with insufficient skilled assistance. “If refraction is decoupled from an eye health examination, many patients will neglect or significantly delay the eye health examination,” Dr. Chou says.

Increasingly, patients continue to become aware of products that could accommodate self-tests but prioritize less-vetted information. Dr. Chou is wary and observes that the existing technologies using digital devices are not yet easy, fast nor accurate enough to create new optical prescriptions without an existing one. “That’s why the services place an emphasis on renewing existing and prescriptions for glasses and contact lenses,” says Dr. Chou.

According to Dr. Chou, until the day that phoropter-based refraction is toppled, prescription renewal and extension will likely get the most play. However, emerging refraction technology may eventually reduce the frequency that patients seek professional eye exams.

How can a practice compete, or co-exist, with the convenience that online services tout?

Cory Collier, OD, of Lakewood Ranch, FL, believes the onus is on practices to provide an exemplary experience that exceeds expectations and reminds patients of the service and satisfaction that comes with in-person interactions. “We have to make it easy to work with our office,” which includes using up-to-date technology, making offices “somewhere patients want to interact” and emphasizing “personal care and relationship building that is simply not available online,” he explains. “If a patient is taking their time to come to your office, they are looking for an interaction, looking for guidance.”

Practice management consultant Gary Gerber, OD, points out that the overall in-office experience is often currently out-of-sync with standards patients derive from their experiences in other realms. “Like it or not, deserved or not, the patient experience in our offices is not only gauged against other healthcare and eye care experiences but also against other retail experiences,” Dr. Gerber says. “If the check out process in an office is more complex than an Amazon shopping cart, we’ve got problems.”

Telemedicine, including artificial intelligence–assisted screenings and other tools, will continue to become more common and routine. Optometrists who resist engaging with these trends could give up valuable leverage in determining their appropriate role.

Howard Purcell, OD, former senior vice president of customer development for Essilor of America and president and CEO of the New England College of Optometry, believes that by staying out of the discussion and hoping online refraction will go away, optometrists will disenfranchise themselves from the shaping of the services’ future—and their own. “Ultimately, as a profession, we have to try to figure out how to use these tools in a positive way,” says Dr. Purcell.

He believes the defensive posture optometrists take in response to online refraction, though often justified, has hindered progress in paving a way for both ODs and companies to collaborate and develop such technology. “I don’t believe that the current models are necessarily the answer but I do believe that we should stay as close to these groups as we possibly can, learn what they’re doing and identify ways to implement it responsibly,” he adds.

Consider a scenario, Dr. Purcell suggests, wherein practitioners could employ online refraction and provide beneficial services to their patients. Suppose a 10-year-old with progressive myopia has a comprehensive eye exam and receives a pair of glasses at your office. Six months later, the child loses his glasses at the beach while on vacation and requires a new pair, ideally without curtailing the trip or seeking out a doctor away from home. Dr. Purcell says with appropriate remote refraction technology in practitioners’ hands, the boy’s family could contact your office for an Rx check to ensure the prescription is still valid, or adjust as needed. This way, you could ensure your patient gets the most accurate prescription for his visual needs that day, not what his prescription was six months ago. “Could an encounter like that be a way we could use some of these technologies to actually improve optometric care?” asks Dr. Purcell.

With appropriate safeguards, remote refraction could become one of those improvements that strengthens the doctor-patient relationship.

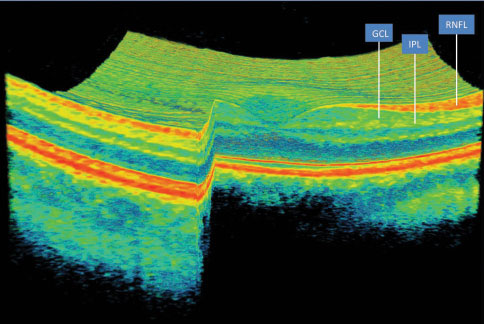

A DeepMind is a Terrible Thing to WasteLondon-based AI firm DeepMind, acquired by Google in 2014, has worked with Moorfields Eye Hospital to develop algorithms for a system that can analyze retinal scans and spot symptoms of sight-threatening eye diseases, such as early detection of diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. The findings, published in Nature Medicine, demonstrate performance in making a referral recommendation that reaches or exceeds that of experts for a range of sight-threatening retinal diseases after training on only 14,884 scans.1 The AI firm’s ultimate objective is to develop and implement a system that can assist the UK’s National Health Service with its ever-growing workload. Accurate AI judgments would lead to faster diagnoses and, in theory, treatment that could save patients’ vision.2

DeepMind’s system consists of two separate networks: a segmentation network that converts the raw optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan data into a 3D tissue map of defined and color-coded slices and a classification network that analyzes the tissue map in order to make decisions about possible diseases and judge the urgency of referral and treatment. The separate networks allow clinicians to check tissue maps and see how the AI came to its final conclusion. The system needs to pass clinical trials and regulatory approval before it can be used on the frontlines of the NHS. DeepMind also wants to validate its results with further testing and refinements to the underlying algorithms, which could take another three to five years. 1. De Faux J, Ledsam JR, Romero-Paredes B, et al. Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nat Med. 2018; 24:1342-1350 2. Ghosh S. Google’s DeepMind AI can accurately detect 50 types of eye disease just by looking at scans. Business Insider. www.businessinsider.com/google-deepmind-ai-detects-eye-disease-2018-8. Accessed October 1, 2018. |

See the Big Picture

Although telemedicine has the potential to assist optometry in accomplishing its goals to improve health outcomes, inappropriate uses have more potential to thwart them. Dr. Gerber notes that refraction and telemedicine get put into the same ‘convenience’ bucket in a patient’s brain. Some practitioners “might not like that, but that is our new reality,” Dr. Gerber says.

These companies and others who behave similarly are providing partial, arbitrarily segmented care based on a test or a product category without regard to the overall health care needs of the consumer. They market themselves as alternatives to licensed medical providers who use those tests or products within the context of their patients’ broader health care needs.7

David Geffen, OD, of San Diego believes it is important for optometrists to separate the battle over online refractions from the larger trend of using telemedicine to help improve care among the patient population.

Dr. Purcell mentions that whenever he lectures on the practice of the future, he has to quickly define what he means when he mentions telemedicine or else he risks losing the crowd. “I find it extremely interesting that we have not done a good enough job of defining what telehealth is,” he notes, explaining that it encompasses both professional and consumer components.

The professional side involves education, communication and connection among health care practitioners. In addition to allowing ODs to compare notes with each other, telemedicine gives practitioners access to experts in related fields. “Can I communicate with the world-renowned leader in cornea, retina or glaucoma to help guide my path through an unfamiliar diagnosis and treatment of that patient?” asks Dr. Purcell. This advance goes unremarked by many but radically improves care with only minimal effort or alteration of conventional modes of practice.

Looking Back and Moving ForwardOptometrists have always been a little wary of disruptive technology. In the March 1978 issue, Review of Optometry published results of a survey on readers’ perception of automation as a threat—autorefraction in particular. A third of over 250 optometrists who responded opposed greater use of automation in optometry and vision care. Nevertheless, “the majority were willing to admit that automation may be the only way to handle future patient loads.” Those opposing automation cited its potential to erode the doctor/patient relationship as a primary reason. They were also concerned with the idea of relying wholly on computer results without checking them further.

Overall, the survey did show that ODs were willing to give new technology a fighting chance—if it delivered on its promises. Interestingly, the survey may provide some guidance regarding the comfort level of today’s ODs amid modern worries over telemedicine. When polled about their approach to buying a new instrument, doctors in 1978 looked first for quality and whether the instrument can do what it was designed for. The autorefractor stopped being an object of fear and derision once practitioners had hands-on experience with it and confidence in its merits. It didn’t obsolete the doctor; rather, it extended the clinic’s capabilities and efficiencies. Blake B. Automation: will it click with today’s O.D.? Review of Optometry. 1978:65-68. |

Consumer applications of telemedicine are even more vast and disruptive. Along with remote refraction’s spotty record, there are more encouraging applications.

Dr. Purcell presents a hypothetical patient interaction over a subconjunctival hemorrhage. A patient calls the office and says their eye is bleeding. Faced with a potential emergency in which response time is precious, the patient could pick up their phone, take a photo of their eye and send it to the office for a quick consult. The doctor could then ask a series of questions to triage the case, based on patient history and relevant health factors. Over the phone, the doctor could tell the patient exactly what to do before they are able to see them in their office in the next two to three days unless something changes.

“Are we comfortable with a scenario like that?” Dr. Purcell asks. “That needs to come from the profession and I fear that today some of those decisions are being made without our input.”

One company following such a model is Eyecare Live, based in California and founded by optometrists. It aims to enhance relationships between doctors and patients and improve collaboration with other health professionals. The company provides HIPAA-compliant communication services for patients with chronic eye conditions, contact lens follow up, and support and triage non-urgent conditions remotely via technology.

“Our present system can enhance the level of care and give you a support system of a network of doctors and professionals that will help you and simplify the process,” says Paul Super, OD, of Los Angeles, a cofounder of Eyecare Live. The OD would be extending the boundaries of the care they provide in the office.

Remote screenings of patients unable to travel is another fertile area for growth. In recent years, communication networks among providers have allowed, for instance, pediatric retina specialists—who are few in number—to screen newborns with retinopathy of prematurity while they’re still in the neonatal intensive care unit. Addressing the epidemic of diabetic retinopathy among rural populations is another instance where telemedicine technology is bringing the clinic to the patient when the converse simply isn’t possible.

It seems inevitable that artificial intelligence will play a role in disease screening in ways that could bring more patients under the umbrella of care, simplify the process of monitoring existing patients, or both (see, “A Deep Mind is a Terrible Thing to Waste). Telehealth provider 20/20Now recently announced incorporation of retinal AI into its ocular exams to enhance images and allow for early detection of disease like diabetic retinopathy.8

Talk it Out

Maybe it comes down to comfort level and familiarity. Still, practitioners remain determined to uphold patient safety and quality of care regardless of the increase in patients who seek a more virtual and convenient experience for all their visits. That day hasn’t come, as not all cases are yet amenable to a telehealth model.

The use of telemedicine as it now exists may be appropriate for basic interactions (nonemergency triage), standard data acquisition, confirming therapeutic results or disease stability and notifying clinicians of changes in chronic conditions. Telemedicine would not be appropriate for initial diagnosis as a replacement for in-person visits and exams.7

Still, there are optometrists out there like Dr. Purcell who believe that having this telemedicine conversation is time well-spent. “I think the first thing we really have to come to grips with is where we are comfortable using remote technology to assist—but not usurp—our role as doctors in patient intake, assessment, triage and management,” Dr. Purcell says. Not every application will be appropriate, but it’s incumbent on the profession to work through it and find its best uses.

Dr. Chou agrees that no one can escape having that realization. “There is an increasing digitization of eye care—movement toward data-driven diagnosis instead of doctor-driven diagnosis,” says Dr. Chou. “It’s happening elsewhere in healthcare as well, not just with our field.”

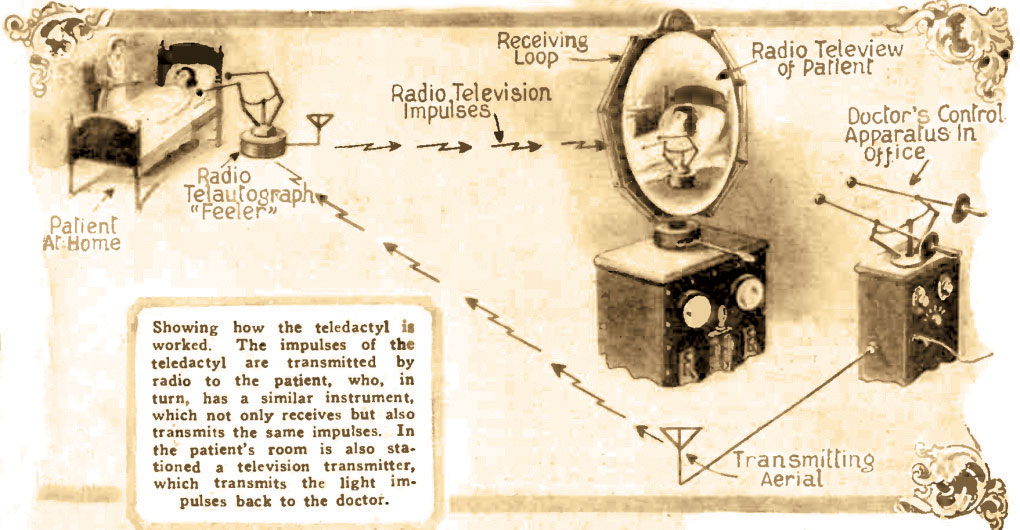

A Jazz Age Vision, Finally RealizedTechnology may finally be bringing telemedicine to doctors’ doorsteps, but the idea itself is almost a century old. Hugo Gernsback, a pioneer of radio and science publishing—the Hugo award for outstanding science fiction is named after him—first laid out a concept for it in a 1925 article, “The Radio Teledactyl,” published in his magazine Science and Invention.

Gernsback, pondering the science of medicine 50 years hence, envisioned a device that doctors would use to tend to their patients remotely in the year 1975.1 The physician of the future would visually examine their patient through a viewscreen while using remote controls and radio waves to manipulate robotic arms (i.e., teledactyls) that had been previously set up at the patient’s bedside. The arms would be sensitive to sound and heat and also could relay that information as well as any tactile response back to the doctor’s controls. Gernsback believed that a good doctor of the future would be able to diagnose a range of ailments using the instrument.2 Commenting on the society and culture of 1925, Gernsback viewed telephone, radio and television as tools for solving innumerable problems. “As we progress, we find our duties are multiplied and we have less and less time to transport our physical bodies in order to transact business, to amuse ourselves and so on,” he observed in the article. In particular, Gernsback noted that doctors in that distant year of 1975 would be too busy to leave their office and visit their patients or, conversely, the patients would not be able to visit the doctor.

Sending the instrument over to the patient’s location, Gernsback wrote. would be cheaper and better for the practitioner. Once the teledactyl was set up, the doctor and machine would do the rest. “In this way, the doctor will be able to treat four or five times as many patients as he could possibly do today,” he added. “And, after all, if he is a really good doctor, he should have many patients.” One year after this article appeared, Hugo Gernsback launched Amazing Stories, the first science fiction magazine (and the inspiration for two Steven Spielberg TV shows of the same name). Gernsback continued to be a lifelong advocate for both science fact and fiction, often using fictional concepts to help inventors and the public envision a better life that might await them. 1. Novak M. Telemedicine predicted in 1925. Smithsonian. Published March 14, 2012. www.smithsonianmag.com/history/telemedicine-predicted-in-1925-124140942/?no-ist. Accessed October 1, 2018. 2. Gernsback H. The radio teledactyl. Science and Innovation. 1925;(142):978,1036. |

Dr. Super also believes that this change will eventually involve all of medicine regardless of one’s interest in and aptitude for technology. “The consumer is demanding certain things, and we’re trying to ensure that we protect patients by modeling our efforts in their best interest, not in ours, so that we can provide the best level of care.”

The drive for telemedicine adds a consumer-driven element that has to be reckoned with. “Clinical accuracy aside—and not to minimize that very important aspect—if consumers want it, it will happen,” Dr. Gerber says.

Dr. Purcell remains optimistic. “I see artificial intelligence, virtual reality, 3D printing and telemedicine all falling into a very similar category of things that will change the profession in a positive way, but without our evaluation or ability to guide that path to some extent, the risks will be greater,” Dr. Purcell says.

Dr. Gerber agrees that practitioners should remain engaged in the process. “Doctors would be smart to stay on top of what’s coming and find ways to embrace it instead of trying to avoid it,” he says. Viewing them as a threat rather than an opportunity “is the heart of the problem,” he says. “The smart play for ODs is to keep their minds open and find ways to leverage the buzz, and when they’re personally, clinically happy with the technology, to use the tech in their own practices.”

Dr. Geffen agrees with this call to action. “Instead of spending our time complaining about this competitive environment, we need to take what is good and enhance it,” he says.

1. Food and Drug Administration. Inspections, compliance, enforcement, and criminal investigations. Opternative Inc. warning letter. Issued October 30, 2017. www.fda.gov/iceci/enforcementactions/warningletters/2017/ucm600029.htm. Accessed October 1, 2018. 2. California Optometric Association. California optometrists caution patients about unapproved, online ‘vision tests’ after FDA warning. COAVision. www.coavision.org/files/05%2009%2018%20Opternative%20Release%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018. 3. Opternative announces international expansion [press release]. Chicago, Il: Newswire; Published July 19, 2018. www.newswire.com/news/opternative-announces-international-expansion-20568242. Accessed October 1, 2018. 4. Vision Monday. Opternative’s doctor locator tool draws fire from some ODs. Published August 13, 2018. www.visionmonday.com/latest-news/article/opternatives-doctor-locator-tool-draws-fire-from-some-ods. Accessed October 1, 2018. 5. Kentucky Legislative Research Commision. 18RS HB 191. www.lrc.ky.gov/record/18RS/HB191.htm. Accessed October 1, 2018. 6. Wright, M. Defining the future of optometry. Oral presentation at: American Optometric Association Optometry’s Meeting;June 2018;Denver, CO. reviewob.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/6-13-18futurepdf.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018. 7. Petito GT. The evolution of telemedicine in eye care. Adv Ophthalmol Optom. 2017:2(1):1-14. 8. 20/20Now implements retinal AI in all of its ocular telehealth exams. 20/20NOW. Published September 18, 2018. www.for2020now.com/20-20now-incorporates-retinal-ai-into-its-ocular-telehealth-exam-to-provide-early-diagnosis-of-diabetic-retinopathy. Accessed October 5, 2018. |