|

A 21-year-old Caucasian male patient presented to our institute with acute-onset visual field defect in both eyes for three weeks. Ophthalmic history, medical history and review of systems were all negative. Entrance visual acuities (VA) were 20/20-1 OU. Intraocular pressures were 18mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS. Extraocular motilities were full, there was no relative afferent pupillary defect, and there was constriction in all quadrants on confrontation visual field testing OU. Anterior segment exam was normal, and posterior segment imaging is available for review.

Take the Retina Quiz

1. Which of these characteristic findings is present on the fluorescein angiography?

a. Arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence.

b. Delayed venous filling.

c. Optic nerve head leakage.

d. All of the above.

2. What is the most likely etiology for the branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO)?

a. Embolus.

b. Hypercoagulability.

c. Leukemia.

d. Susac syndrome.

3. Which of the following is NOT considered part of the characteristic clinical triad seen in this disease?

a. BRAOs.

b. Encephalopathy.

c. Interstitial keratitis.

d. Sensorineural hearing loss.

4. What is the most appropriate treatment for this disease?

a. Observation.

b. Embolic workup.

c. Hypercoagulable workup.

d. Immunosuppression.

5. What is the natural history of this disease in the absence of intervention?

a. Progressive encephalopathy and eventual dementia.

b. Progressive hearing loss and eventual deafness.

c. Progressive multifocal BRAOs and eventual blindness.

d. All of the above.

|

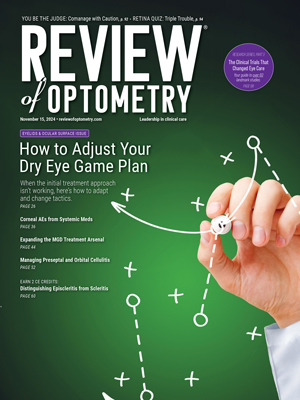

Fig. 1. Widefield Optos fundus photos of right (A) and left (B) eyes. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

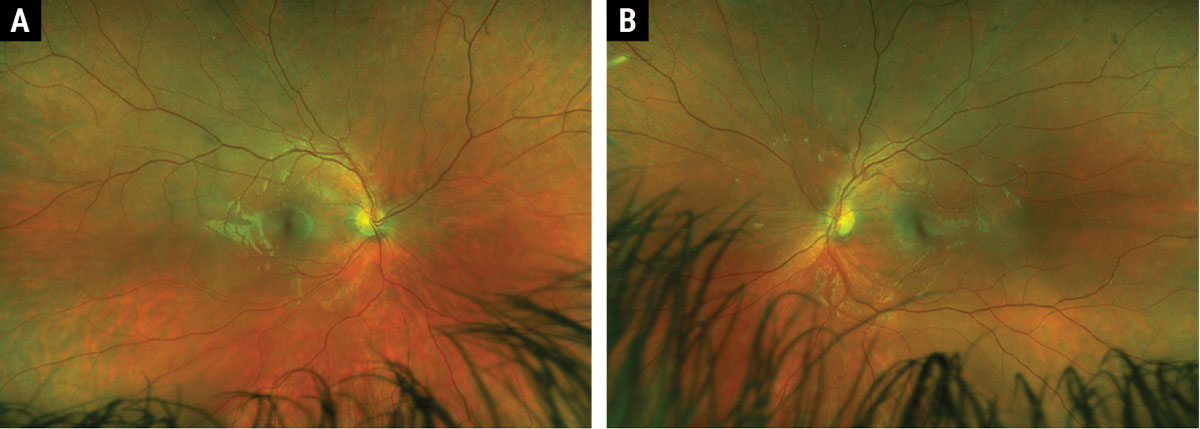

Fundus examination disclosed arteriolar narrowing OD>OS (Figure 1), and fluorescein angiography (FA) showed multifocal arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence OU (Figure 2). Review of symptoms was negative at presentation; extensive infectious and inflammatory lab studies were ordered and found to be negative. Within about six weeks, there was new-onset right-sided tinnitus and intermittent new-onset headaches, raising concern for Susac syndrome. Neurology was consulted, and all serologic and radiographic studies were negative. The patient responded well to empiric trials of oral prednisone but repeatedly flared during taper. Serial neuroimaging was performed due to persistent concern for Susac syndrome, which eventually demonstrated corpus callosal lesions, and that diagnosis was made.

Discussion

Melanin is thought to be protective against tumor formation.5 Risk factors for developing UM include fair skin complexion, light-colored iris, inability to tan, choroidal nevus, ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis, dysplastic nevus syndrome and genetic predisposition (e.g., mutation in the BRCA1-associated protein-1; BAP1).2,4 BAP1 gene mutations carry an increased risk of developing cancers of the eye, kidney, skin and mesothelium, as well as for metastatic disease.4

UM may be described as being anterior (involving iris) or posterior (involving the ciliary body and choroid).1,4 The current convention for classification of posterior UM was updated in 2013 to address primary tumor anatomic features (T), regional lymph node metastasis (N) and systemic metastasis (M).2,6 The lesions are first classified as small (T1), medium (T2), large (T3) or very large (T4) based on lesion thickness and basal diameter, then further stratified into one of seven possible stages (I, IIA, IIB, IIIA-C and IV) based on presence of ciliary body and/or extrascleral extension.1,2,6

The differential diagnosis includes choroidal nevus, choroidal hemangioma, peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), or subretinal/sub-RPE hemorrhage.4 Enhanced-depth imaging OCT can characterize smaller, posterior lesions, but ultrasonography remains the most important diagnostic tool.2

A-scan features include low amplitude internal reflections with occasional spikes that may represent intrinsic tumor vascular pulsations.2

Typical B-scan features include acoustic hollowing, choroidal excavation and orbital shadowing.1,2,4 Once Bruch’s membrane has been breached, the lesion takes on a typical “collar-button” or “mushroom” configuration on ultrasound and may show the characteristic “double circulation” on fluorescein angiography due to intrinsic tumor vascularity overlying the highly vascularized choroid.1,2,4

|

Fig. 2. Widefield Optos fluorescein angiogram early and late phase of the right eye (A and B) and late phase of the left eye (C). Click image to enlarge. |

Susac syndrome may present initially with bilateral BRAOs, hearing loss or migraines; it presents as a complete triad in only 13% of patients and may take months or years following initial symptom onset for the complete triad to manifest.5,6 Susac syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, and the European Susac Consortium (EuSaC) proposed their diagnostic criteria in 2016. Definite Susac syndrome is defined as patients with an unequivocal clinical and/or paraclinical involvement of all three main organs (i.e., a complete clinical triad), and probable Susac syndrome is defined as patients with an unequivocal involvement of two of the three main organs.5 The manifestation of only one organ should be considered possible Susac syndrome.5

Retinal involvement is defined as at least one of the following: (1) at least one BRAO seen clinically or on FA, (2) focal segmental staining of the arterial wall (i.e., arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence on FA near the site of obstruction) or (3) sectoral thinning of the inner retina seen on optical coherence tomography (i.e., evidence of prior retinal ischemia).5

BRAOs in Susac syndrome can be bilateral and multifocal and may have yellow-white midsegment arterial wall plaques (Gass plaques) that can appear as long “silver streaks” when confluent.2,4,7,8 Of note, these plaques are transient and distinct from typical embolic plaques in both location and appearance.7, 8 Typical visual symptoms include photopsia, negative visual phenomena, scintillating scotoma and amaurosis fugax.2,4,8

Clinical exam is best aided by FA, as the damaged endothelium-lined arterioles will show arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence in the form of staining or leakage.4,5,8,9 Presence of angiographic multifocal arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence is considered nearly pathognomonic for Susac syndrome and satisfies the criterion for retinal involvement.4,5,7-9

It is important to acknowledge that arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence can be seen even in seemingly “normal” appearing vessels on clinical exam, suggesting that the endotheliopathy is widespread and disseminated throughout the fundus, even when complete arteriolar occlusion is not present.7 Therefore, FA is one of the most sensitive imaging modalities to objectively detect persistent disease activity or subacute reactivation.5,8,9 Retinal neovascularization is a very rare complication, so prophylactic retinal photocoagulation is generally not indicated.6

Brain involvement is defined as at least one new clinical neurological symptom along with characteristic findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).5 Clinical findings can include altered consciousness, cognition or behavior, new focal neurological symptoms or new-onset headache/migraines.5 While headache is a non-specific finding present in much of the normal population, it is present in 80% of Susac syndrome patients and is therefore considered a relevant feature of Susac syndrome within six months of other associated findings.5 MRI is the preferred neuroimaging modality and will show characteristic T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery multifocal, round, hyperintense brain lesions that must involve the corpus callosum.5

Vestibulocochlear involvement is defined as at least one of the following: (1) new tinnitus, (2) new hearing loss or (3) new peripheral vertigo.5 Hearing loss should be objectively quantified with pure-tone audiometry of low and mid-tone frequencies or brainstem auditory evoked potentials, and peripheral vertigo can be supported by caloric testing of the vestibular organ, nystagmography and/or vestibular evoked myogenic potentials.4,5 Both clinical findings and supportive vestibulocochlear studies are necessary to satisfy this criterion.5 Hearing loss development can be mild and insidious (over several months) or acute (overnight); auditory studies may be more heavily relied upon in encephalopathic patients (inability to report symptoms).4

More recently, it has been suggested that evidence of arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence (FA) and central corpus callosal lesions (MRI) are such pathognomonic features of this disease that these two items may be sufficient to make a diagnosis of definite Susac syndrome as opposed to probable Susac syndrome based on EuSaC criteria.10 The author makes clear distinction that arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence at the site of a BRAO not specific enough to Susac syndrome; thus, arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence present away from a BRAO should be considered confirmatory for definite Susac syndrome.10

|

|

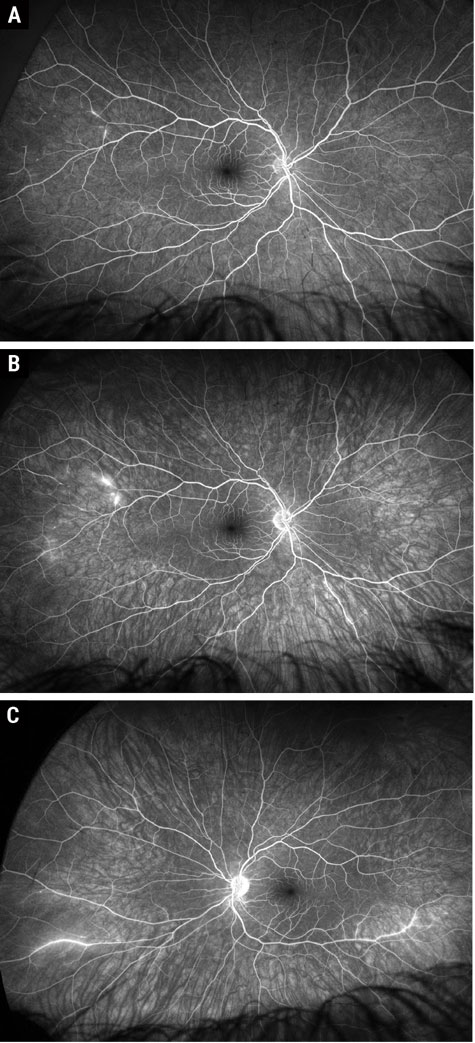

Fig. 3. Widefield Optos fluorescein angiogram early (A and B) and late phases (C and D) of both eyes at 10-month follow-up. Click image to enlarge. |

Management

There are no ongoing or published randomized controlled trials on Susac syndrome. While some of these patients have had self-limiting disease in the absence of treatment, immunosuppression with high-dose corticosteroid therapy is generally combined with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) as first-line therapy given rapid efficacy.4,6,10 Corticosteroid is typically administered as IV pulses of methylprednisolone followed by a taper to oral prednisone and combined with daily IVIg that is then administered monthly for at least six months.4,6,10 Recalcitrant cases may require escalation to cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, rituximab or mycophenolate mofetil.6,10

Serial MRI and FA are used to monitor for persistent disease activity or subacute reactivation and should guide the decision to prolong or escalate treatment.10 A patient is considered to be in remission when the patient is asymptomatic and shows radiographic/angiographic inactivity on MRI and FA.10 Prognosis is generally good, as it does not result in death or paralysis, but about 50% of patients suffer irreversible hearing loss or mild-to-moderate dysexecutive cognitive sequelae that can impact their ability to sustain certain occupations.2,4

Patient Resolution

Our patient presented with only ophthalmologic findings and had negative neuroimaging studies performed early in his course. Within months, the triad manifested as tinnitus, headaches and visual disturbances corroborated by positive MRI and FA findings characteristic of Susac syndrome. As in our patient, many do not present with a fully manifest triad, and so the clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion and reassess review of systems at subsequent visits. Our patient initially did well with corticosteroid and IVIg therapy but reactivated about 10 months later evidenced by extensive multifocal arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence OU (Figure 3), prompting escalation to mycophenolate mofetil. The patient has since been monitored without angiographic evidence of activity.

Retina Quiz Answers

1: a, 2: d, 3: c, 4: d, 5: d

Dr. Aboumourad currently practices at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. He has no financial disclosures.

1. Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979;29(3):313-6. 2. Pereira S, Vieira B, Maio T, et al. Susac’s syndrome: an updated review. Neuroophthalmology. 2020;44(6):355-60. 3. Marrodan M, Fiol MP, Correale J. Susac syndrome: challenges in the diagnosis and treatment. Brain. 2022;145(3):858-71. 4. Susac JO, Egan RA, Rennebohm RM, Lubow M. Susac’s syndrome: 1975-2005 microangiopathy/autoimmune endotheliopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257(1-2):270-2. 5. Kleffner I, Dörr J, Ringelstein M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for Susac syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(12):1287-95. 6. David C, Sacré K, Henri-Feugeas MC, et al. Susac syndrome: a scoping review. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;21(6):103097. 7. Egan RA, Hills WL, Susac JO. Gass plaques and fluorescein leakage in Susac syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2010;299(1-2):97-100. 8. García-Carrasco M, Mendoza-Pinto C, Cervera R. Diagnosis and classification of Susac syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4-5):347-50. 9. Rennebohm R, Susac JO, Egan RA, Daroff RB. Susac’s syndrome--update. J Neurol Sci. 2010;299(1-2):86-91. 10. Egan RA. Diagnostic criteria and treatment algorithm for Susac syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2019;39(1):60-7. |