|

A 92-year-old white male presented for evaluation of acute diplopia. He described it as horizontal, worse when looking to the left and only noticeable at distance. Pertinent medical history included hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, depression and GERD. His current medications included lisinopril, glucophage, atorvastatin, omeprazole and mirtazapine. He denied head pain, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, weakness or increased fatigue.

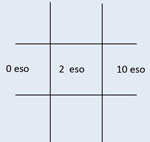

Best corrected visual acuity was 20/25 OU. His extraocular motilities appeared full in all gazes. Pupils were equal, round and reactive to light with no afferent pupillary defect. Cover test was ortho in right gaze, a 2PD ET in primary gaze and a 6ET in left gaze consistent with a left sixth nerve palsy.

Anterior segment exam was unremarkable. He was pseudophakic. Cup-to-disc ratio was 0.2/0.2 OU with no disc edema, pallor or hemorrhage noted. His retinal exam was otherwise unremarkable.

Given his age, isolated sixth nerve palsy and vasculopathic risk factors, we decided to follow up in one month without any additional testing. Shortly after, the patient was hospitalized for unspecified rectal bleeding. He was in and out of the hospital and wasn’t able to follow up until approximately three months later. At that follow up, he reported arm and leg weakness and increased fatigue. Upon questioning he admitted to facial pains located around his temples that started a few days prior. His sixth nerve palsy and cover test measurements were slightly worse (ortho in right gaze, 2PD ET in primary gaze and 10PD ET in left gaze). His vision was stable and there was no disc edema or signs of ischemic optic neuropathy. Because of his symptoms, we ordered a STAT ESR and CRP, which measured 62 and 8.0, respectively. The patient was referred to his internist for evaluation of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and giant cell arteritis (GCA). Based on his constitutional symptoms, worsening sixth nerve palsy, elevated ESR and CRP, he was tentatively diagnosed with vasculitis-induced ocular motor palsy and treated with 40mg of prednisone. A temporal artery biopsy to confirm GCA was deferred due to his age. He returned for a follow up ophthalmic examination one week later and reported that the diplopia had resolved three days after starting the prednisone, and he was feeling significantly better. His cover test measurements were ortho in right, primary and left gazes. He has been tapering the prednisone per his internist’s advice. As of our last visit, his ESR was 22 and his sixth nerve palsy was completely resolved.

| |

| The patient presented with an esotropia worse on left gaze consistent with a left sixth nerve palsy (left). On follow up exam, the sixth nerve palsy worsened (right). |

Discussion

PMR is a chronic inflammatory disorder usually seen in patients over 50.1 It primarily affects proximal muscles and joints and is associated with GCA in 18% to 26% of cases.2

The hallmark symptoms of GCA are headache, jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, neck and shoulder pain, as well as fatigue and weakness. Although PMR often begins prior to the onset of GCA, it can be difficult to predict its conversion since up to 50% of PMR patients, even without headache, have been reported to have a positive temporal artery biopsy.2 While symptoms of transient ischemia have been described in PMR patients, they suggest progression to GCA.

With exclusion of patients receiving low-dose systemic steroids for PMR, symptoms of isolated transient ischemia without concurrent headache or other systemic complaints in a patient with GCA are uncommon. However, atypical cases have been reported. The most unusual scenarios involve patients with a normal ESR, no systemic complaints and a positive cranial neuropathy, or patients with ophthalmologic or neurologic findings in the absence of systemic complaints and a normal ESR.1 Other rare presentations of GCA include acute internal carotid artery, middle cerebral artery, posterior cerebral artery and basilar artery transient ischemic attacks.1 Although rare, cranial nerve palsies, especially the oculomotor nerve and abducens nerve, have been associated with GCA.3-7 Researchers believe this is a result of arteritis affecting the blood supply to the nerve.8 GCA prevalence in individuals over 50 is 133 in 100,000; however, the prevalence increases to 843 in 100,000 in individuals older than 80.1

Our patient’s presentation was atypical because he didn’t develop symptoms of PMR/GCA until three months after presenting with the sixth nerve palsy. Because of the immediate resolution of his diplopia and nerve palsy after starting prednisone, we feel this was related to vasculitis and not microvascular. It was most likely a lower grade inflammation exacerbated by his medical issues and hospitalizations.

| EULAR-ACR Classification Criteria for Polymyalgia Rheumatica* | ||

| Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) | Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR) | |

|

| |

| *Classification as PMR requires 4 points; for giant cell arteritis (GCA), three criteria for the classification of GCA must be fulfilled.1 Modified from EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CCP, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies.2 | ||

Although most isolated nerve palsies are microvascular, the clinician should maintain a suspicion for other etiologies. No general consensus exists regarding management of isolated sixth nerve palsies in individuals over 50. Some authors recommend monthly observation for up to three months before considering neuroimaging and laboratory studies (assuming there are no other neurologic deficits or symptoms suggestive of a process other than microvascular disease).9 Others recommend neuroimaging and laboratory studies at initial examination.3,5

We typically do not order an ESR or CRP in individuals with isolated third or sixth nerve palsies unless symptoms to suggest GCA. Apply good clinical judgment when managing these cases. Test ESR and CRP in patients over 50 presenting with sixth nerve palsies when suspicion of GCA exists or if the nerve palsy worsens or fails to resolve.

After managing this patient and because the prevalence of GCA increases exponentially after age 80, we believe this increased prevalence is high enough to warrant early serology, including an urgent ESR and CRP despite the isolated nature of the palsy or any pre-existing vascular risk factors.10 We recommend obtaining these tests as a precaution in this subset population to avoid a delay in diagnosis since ophthalmologic involvement, including ocular motor paresis, unilateral visual loss, or both, will develop in 17% to 55% of untreated patients.1

1. Kupersmith MJ, Berenstein A. Neuro-vascular neuro-ophthalmology. Springer-Verlag Berline; Heidelberg, 1993.2. Dasgupta B, Cimmino MA, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. 2012 provisional classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:484-92.

3. Caylor T, Perkins A. Recognition and management of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Nov;88(10):676-84.

4. Tamhankar M, et al. Isolated third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies from presumed microvascular versus other causes. Ophthalmology. 2013 Nov;120(11):2264-9.

5. Arai M, Katsumata R. Temporal arteritis presenting with headache and abducens nerve palsy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2007 Jul;47(7):444-6.

6. Thurtell M, et al. Third nerve palsy as the initial manifestation of giant cell arteritis. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2014;34:243-5.

7. Davies GE, Shakir RA. Giant cell arteritis presenting as oculomotor nerve palsy with pupillary dilation. Postgrad Med J. 1994 Apr;70(822):298–9.

8. Asensio-Sanchez VM, et al. Third nerve palsy as the only manifestation of occult temporal arteritis. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2009;84:395-8.

9. Fisher CM. Ocular palsy in temporal arteritis. Minn Med. 1959;42:1258-68.

10. Goodwin D. Differential diagnosis and management of acquired sixth cranial nerve palsy. Optometry. 2006 Nov;77(11):534-9.