Vision Therapy Snub Unwarranted

I was very discouraged to see one of the major optometric journals publish an article about amblyopia (“The Generalist’s Guide to Amblyopia,” January 2021) without mentioning vision therapy as a treatment option. While VT may not be common practice for most eyecare professionals (though it should be the first line of treatment), it should be worth mentioning in an article about amblyopia.

It concerns me that optometry has aligned itself with the medical model and vision has been simplified to no more than a concern for visual acuity. We appear to have ignored our history and the principles that our unique profession was founded on; namely, the function of vision and the pinnacle of vision function, binocularity. Current research clearly shows that functional amblyopia exists because the two eyes cannot be fused in the brain. To truly solve amblyopia, one must solve the binocular problem at the brain level. How is patching a child with amblyopia (making them monocular) going to improve binocular vision? It cannot be that training an amblyopic eye independently rather than the visual system as a unit constitutes best practices.

It astounds me that optometry will consult and/or refer to ophthalmology but we do not refer (or even recognize) those within our own profession who successfully treat amblyopia daily. When will mismanagement of amblyopia be held to the same standards as mismanagement of glaucoma or a retinal condition?

Therapy for amblyopia has advanced much further than managing the condition with an eye patch alone. Let’s stop simplifying vision and thereby degrading our profession. The profession has expanded but let us not move the profession away from our roots: the diagnosis and treatment of functional vision problems.

—Megan Lott, OD, FCOVD

Belle Vue Specialty Eye Care, Hattiesburg, MS

Young ODs Can Reinvigorate Established Practices

I read with interest the February editorial (“Can’t Get There From Here”) on the plight of new graduates struggling to find positions that use their skills to the fullest.

There are—or should be—plenty of opportunities for young doctors to expand private practices by offering their more robust skill set to established offices. Many older ODs did not have the outstanding education that’s offered today in our training programs. These senior doctors can bring newer services into their practices simply through a hire rather than extensive training on their own part.

In addition to your example of glaucoma, newly minted optometrists have the potential to offer an established practice skills in any of the following realms: AMD, night vision complaints, diabetes and diabetic retinopathy, dry eye and MGD, computer-related visual symptoms, concussion and head trauma, cataract comanagement, eyelid lumps and bumps, blepharochalasis and ptosis, identification of retinal lesions, ocular safety of systemic meds, neurological conditions like MS or Parkinson’s, and specialty contact lenses, which are enjoying a renaissance thanks to sclerals.

Established ODs who say they can’t afford to pay the new grads should consider the tremendous increase in revenue these services will bring to their practices just among the established patients already being seen in their offices, let alone new ones. Some creative salary structuring can minimize the liability, such as a compensation plan giving the new OD a somewhat smaller base salary and 30% to 50% of the new fees that are collected. Both parties win! Finally, the established OD finds an eventual buyer for their practice—something they frequently complain is not available.

For the young OD, benefits are equally desirable, including income growth potential that’s absent in corporate positions, the career satisfaction of using all the skills and training that they invested their time in developing, and the security in knowing that an equity share provides a valued asset when the time comes to retire.

—George E. White, OD, FAAO

Residency director (ret.), Pennsylvania College of Optometry

Corrections

|

Eso or exo? A figure in the February article, “An Action Plan for Assessing Double Vision,” incorrectly described the results of Maddox rod testing as an eso deviation when it was an exo. The corrected caption appears in the online version.

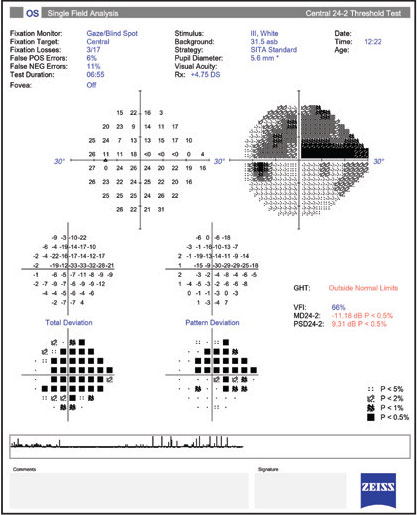

Visual field not so bad. A perimetry report in the February article, “Breaking Down Visual Fields in Glaucoma,” printed incorrectly, suggesting more end-stage disease than was present in the case. The online version has been updated and the correct result is reproduced here as well.