Trouble at the SurfaceMedication, infection, genetics, poor hygiene—these are only a few factors that contribute to ocular surface health. This month in Review of Optometry, experts weigh in on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment and management of numerous diseases affecting this delicate part of the eye. |

We have witnessed an impressive surge of therapeutic advancements for the treatment of ocular surface disease (OSD) in the last two decades. Increased awareness of dry eye disease (DED), availability of new therapies targeting specific etiologies and greater understanding of the multifactorial nature of OSD by fellow clinicians have made these treatments a viable in everyday practice.

Autologous serum eye drops (ASEDs) remain one of the most advanced therapeutics for acute and chronic ocular complications. The primary goal of this article is to guide you in overcoming some of the common obstacles and limitations we may face when prescribing these treatments; specifically, which patients are likely candidates, when and how to add this modality to your practice, as well as how to assess a patient’s progress.

Autologus Serum

The therapeutic benefit of ASEDs has been observed in studies dating back to 1975 in patients with multiple systemic disease with ocular involvement and post-surgical ocular surface pathology.1 Since then, its clinical use has been broadened to cover a wide range of OSD cases such as severe DED, exposure keratopathy, neurotrophic keratitis, Sjögren’s syndrome, Steven Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, graft versus host disease (GVHD), chemical burns, trauma and post-surgical complications. They are also used for other etiologies such as herpetic keratitis, trauma-based recurrent corneal erosions and many other conditions.2-5

Some of the unique biochemical characteristics that make ASEDs the “Holy Grail” of topical treatments include pH, osmolarity, micronutrients such as vitamins A and E, proteins such as albumin and fibronectin, and platelet-derived epitheliotrophic factors that are similar to that of human tears.2,3 ASEDs therefore play an important role in the epithelial healing process of the ocular surface by having anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antiangiogenic properties.

The Best Candidates

Whether it’s your first time considering ASEDs or you’ve had a successful track record of using them, it is helpful to review common clinical applications and scenarios where these drops can be applied in practice. One of the more classic examples include recalcitrant cases of severe aqueous deficient dry eye after maximum topical treatment and anti-inflammatory agents. The second involves post-surgical cases with advanced OSD where there is recurrent epithelial compromise or delayed epithelial regeneration. Next is persistent epithelial defects in chronic OSD such as GVHD, cicatricial pemphigoid, exposure keratopathy, neurotrophic keratitis, chemical burns and radiation keratopathy. Lastly, consider ASEDs when dealing with ocular neuropathic pain, also known as “pain without stain” or corneal neuralgia.6

However, if we strictly look at patient candidacy based on disease severity in advanced DED, those who would benefit from ASEDs can be classified as patients who have not shown significant improvement using the conventional steps one and two staged management and treatment recommendations as per the TFOS DEWS II report.3 This classic scenario can be seen in patients that are insufficiently or unsuccessfully managed who suffer from a systemic autoimmune-based etiology such as Sjögren’s syndrome or GVHD. Other common cases include medication and/or preservative-associated persistent epithelial defects found in over-the-counter decongestants and lubricants, and toxic keratoconjunctivitis from chronic use of topical glaucoma medications.6 Of course, this is not an exhaustive list, so keep in mind the complex and multifactorial nature of the disease when treating patients, including any impairment to the lacrimal functional unit from environmental, anatomical, endocrinologic and cortical causes.3,5

Implementing ASEDs

There are many instances where one might want to either switch to ASEDs or incorporate them as an adjunct therapy. Many clinicians consider ASEDs as a late-stage treatment option, and TFOS DEWS II also places it as step three in their treatment paradigm. However, I believe the direction and decision to incorporate such treatment should be based on multiple factors aside from direct clinical signs. For example, one should pay close attention to visual acuity changes throughout the patient’s therapeutic journey. We know that chronic OSD can wax and wane over time and can have an effect on visual acuity in some patients, so watching out for any reduction in acuity or increasing subjective visual complaints should prompt the clinician to reanalyze the current treatment and explore advanced treatment options such as ASEDs.

Another scenario is when a patient has a non-healing case of persistent superficial punctate keratitis and has shown little to no improvement despite topical immunomodulators, aggressive topical lubrication, amniotic membranes grafts and/or steroids. In this instance, you could use ASEDs to potentially replace a medication in their regimen that has failed to provide adequate benefit or one that is more difficult to continue using based on side effects, cost or long-term accessibility.

If replacing a medication could cause some potential regression, you could then add ASEDs and monitor the patient’s progress closely to determine when or if their regimen can be simplified. Most patients at this level of treatment suffer from chronic conditions, therefore regimen longevity and medication compliance are of utmost importance.

|

|

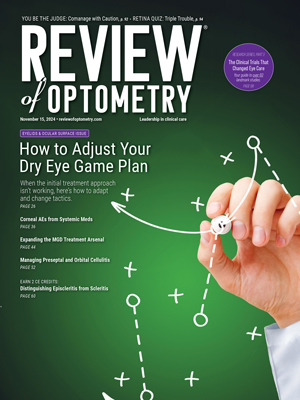

Baseline sodium fluorescein photos prior to ASEDs (A, B) and post-40% ASED use (C, D). Click image to enlarge. |

Overcoming Barriers

Aside from logistics and accessibility, one of the largest barriers to ASEDs is the economic cost and financial sustainability of the treatment. While there may be some exceptions to specific plans, ASEDs are usually not covered by insurance carriers as it is currently not an FDA-approved therapy for ocular surface disorders.2 Financial cost can range greatly depending on location, dosage and concentration used, lab fees for blood draws and compounding pharmacy preparation fees. These fees range from $200 to $450 for a 90-day supply and up depending on which company is used. Some pharmacies may charge a bundled price, including the blood draw, if they have an in-house phlebotomist or contract a third-party phlebotomy company that assists with mobile at-home services and logistics. Unfortunately, or fortunately, the price paradox is that for some uninsured patients or those with either high deductibles or no coverage, the out-of-pocket cost for ASEDs is sometimes less than what other novel FDA-approved therapies, artificial tears and other over-the-counter products may cost.

Access to nearby accredited sterile compounding pharmacy can be challenging, especially in rural areas, so one must consider the ability for a patient to coordinate this appropriately or obtain assistance from a family member or caregiver as needed. Some companies, such as Vital Tears, facilitate the process for both the provider and the patient by having a service specialist contact the patient, schedule the blood draw at a local partnering lab or mobile phlebotomist, collect payment, process the serum tears and ship within 48 hours, and review the proper usage and storage for ASEDs. This can greatly reduce the burden for both patient and provider, as well as increase compliance.

Most studies have not shown significant adverse events with ASEDs; however, the risk of microbial growth does exist when using preservative-free therapies. Therefore, patients should be advised on proper handling and storage to minimize risk of microbial contamination especially in patients with a compromised ocular surface.4,6 Irritation, redness, changes to vision and swelling should not occur with ASEDs. If a patient experiences any of these symptoms, instruct them to discontinue use immediately and return for a follow-up consult to rule out other etiologies or possible contamination of the batch. If a patient does not meet serum donor criteria and screening (good venous access, adequate Hb levels, void of blood-borne diseases), is unable to store them under refrigeration, has limited mobility or does not tolerate repeated blood draws, then one can consider allogeneic serum drops, as studies have shown to be as effective as ASEDs and have similar tolerability.2

Adding ASEDs to Your Practice

Aside from companies such as Vital Tears that specialize in processing and dispensing of ASEDs, you could also partner with local independent labs, private sterile compounding pharmacies or work with hospital-associated labs to build a referral network that could cut down on cost and improve patient accessibility. Most companies should be on board partnering with your office to expand care and likely offer other sterile compounded preservative-free topical treatments to replace existing branded or preserved products. Depending on your practice modality, specialty, state regulations and patient volume, you can even consider bringing this specialized service directly into your practice to increase patient access and expand your referral network.

For most of us in private practice, working to establish relationships with local businesses and minimize the patient’s overall cost and burden is a win-win scenario. Meet with local lab representatives or compounding pharmacists to compare pricing and learn about their protocols.

Another approach when incorporating ASEDs is to consider using this option earlier in the disease process, if applicable, instead of waiting to reach a specific severity target. In my experience, for example, a moderate-to-severe dry eye patient who historically cannot tolerate commercially available immunomodulators or anti-inflammatories tends to have a better prognosis, quality of life and a greater chance of preventing further corneal compromise if ASEDs are introduced earlier or pulsed during certain times of the year when flare-ups are expected. Of course, those who have OSD secondary to systemic autoimmune disorders require adequate systemic management and also lifelong ophthalmic control, so tapering or temporary discontinuation may not be feasible.

|

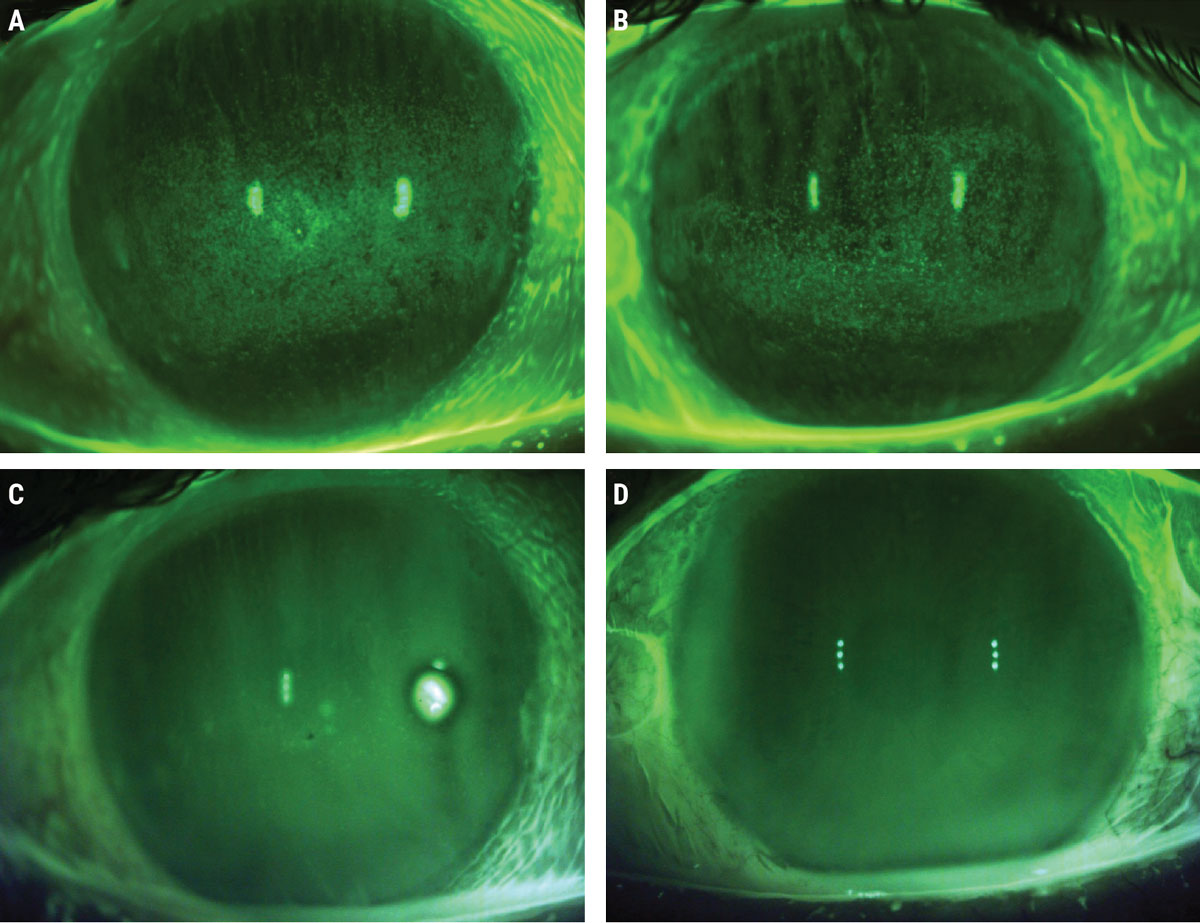

A batch of six 3mL droptainers of 20% ASEDs. Photo: Joshua Keller, PharmD. Click image to enlarge. |

Pharmacy's Policies and Protocols

The following steps are simply guidelines and may vary based on individual compounding pharmacy’s policies and protocols to process and dispense ASEDs. Be sure to contact the specific pharmacy in your area to learn more about their exact protocols and preferences.

Step one: submitting prescriptions. These can be submitted to a compounded pharmacy just like any other prescription medication; verbally, faxed, as a walk-in prescription or via electronic prescriptions. It will include the autologous serum concentration needed, dosage, length of therapy and number of refills.

A prescription example may read: ‘Autologous serum eye drops (40%), Sig: Instill one drop in both eyes six times per day x 60 days, Refills: 1’.

Once the prescription is processed by the pharmacy, a phlebotomist receives the order, schedules the patient for the blood draw and collects between six and 12 serum separator tubes of whole venous blood depending on the dose, quantity and the patient’s ability to donate the necessary volume. The serum separator tubes are also known as “tiger tubes” due to their gray/red speckled colored tops and do not contain anticoagulants, but rather a clot activator and serum separator gel. The tubes are refrigerated during transportation if collected off-site and most pharmacies will not compound ASEDs with aged blood over five days since the initial draw. Also, not all pharmacies have a phlebotomist on-site, so depending on the pharmacy, you may need to submit a lab order and prescription separately.

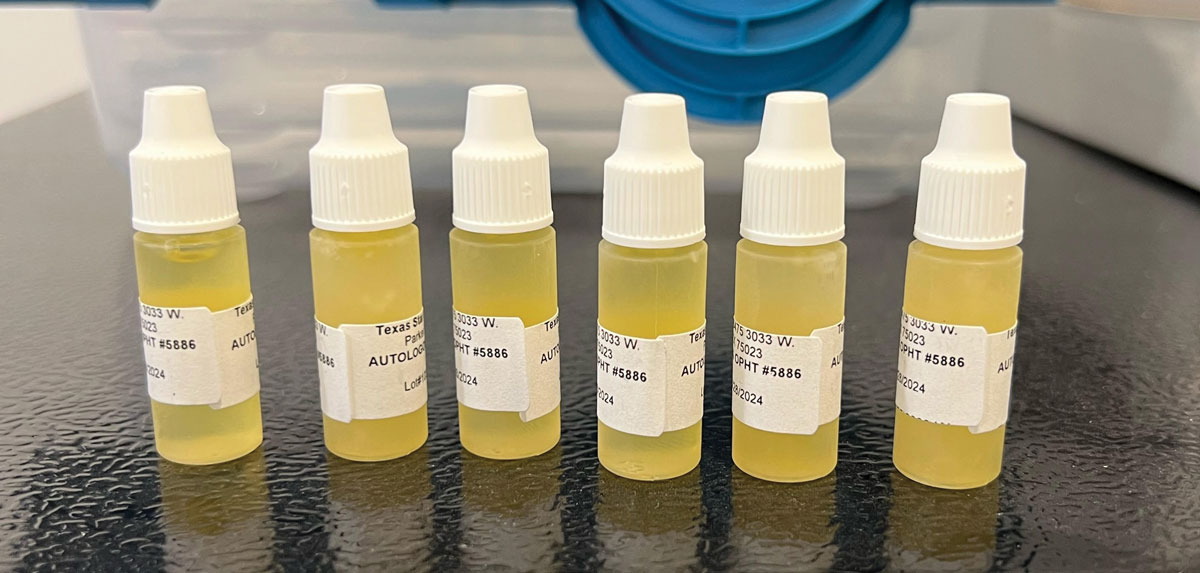

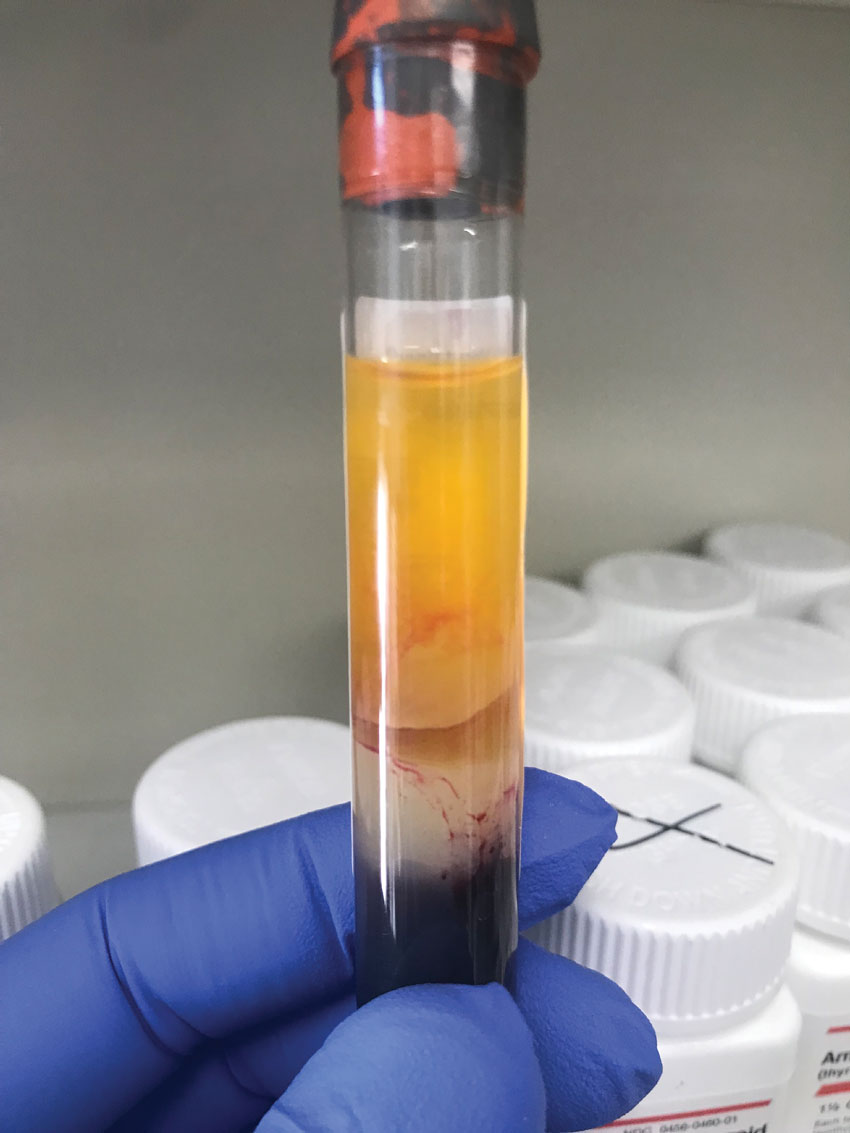

Step two: centrifuged, combined. The tubes are then centrifuged to separate the serum from the rest of the blood. The pharmacist will first inspect the tiger tubes to ensure they are suitable for use and contain about 3mL of clear/yellow serum that is easily retrievable from the top of the tube. The serum cannot be cloudy or red, as this indicates that the serum may contain red blood cells and is not suitable for therapy.

Next, the tubes are combined with appropriate amount of 0.9% sodium chloride solution in a sterile lab, filtered for sterility and dispensed into 3mL eye drop bottles known as droptainers. The total volume dispensed is usually between 36mL and 72mL, so most patients can expect to get between 12 and 24 bottles, respectively. Assuming a conservative conversion of 15 drops per mL of serum, due to the natural variation in viscosity and storage temperature, this can yield anywhere from 540 drops to 1,080 total drops. The duration of the supply depends on the concentration and dosage used.

Assuming six tubes of blood yield 18mL of serum and the patient is prescribed a common dose of six times per day, a 20% concentration can last up to 112 days (although the pharmacy will only dispense a 90-day supply), 40% up to 56 days and 80% up to 28 days. The phlebotomist will generally collect more tubes of blood when a higher concentration is prescribed, as the serum is less diluted.

Step three: properly storing drops. Although most pharmacists will perform a medication review on how to use and store the drops with the patient, the eyecare provider should reiterate the importance of storing the supply of ASEDs in the freezer. Patients are asked to then thaw one bottle at a time stored in the refrigerator between administrations. The in-use bottle should be discarded after seven days.

Due to the preservative-free nature of ASEDs, patients wash hands and practice good hygiene when handling the dropper. They are encouraged to inspect for particulate matter in the dropper prior to use, and when in doubt, use a new bottle.

|

|

Separation of blood components. Note the serum is bright yellow, clear and free from visible particles and red blood cells. Serum (top), red blood cells (bottom), serum separator (middle). Photo: Joshua Keller, PharmD. Click image to enlarge. |

Likely Outcomes

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis including seven randomized controlled trials with 267 subjects on the outcomes of ASEDs for DED indicated that ASEDs outperformed artificial tears in both subjective symptoms, as per the ocular surface disease index (OSDI) scores, as well as objective data such as vital dye staining scores (rose bengal) and tear film break-up time (TBUT).6,7 ASEDs can play an important role in corneal neuro-regenerative therapy for patients with corneal neuropathy and photoallodynia at the subbasal nerve plexus by improving nerve density and morphology.8,9 The benefit of this treatment is that ASEDs have been shown to have a quick symptomatic improvement in as little as 10 days. It is helpful for both the patient and practitioner to determine its efficacy and candidacy to decide if the treatment is appropriate.3,10 With that being said, I also tend to prescribe ASEDs in patients who may have ocular neuropathic pain or photoallodynia due to its corneal regeneration properties, as these patients—despite clinical signs on examination in some—have impaired social functioning and tend to experience difficulty with different light sources and brightness, which may lead to anxiety, depression and lower quality of life.

I also educate my patients to maximize their outcome not only during therapy but also leading up to their blood draw. I encourage them to prioritize restful sleep leading up to their draw, stay hydrated to increase blood volume, eat a balanced diet and avoid foods high in saturated fats, manage stress with breathing exercises or yoga and avoid diuretics such as caffeine or alcohol.

|

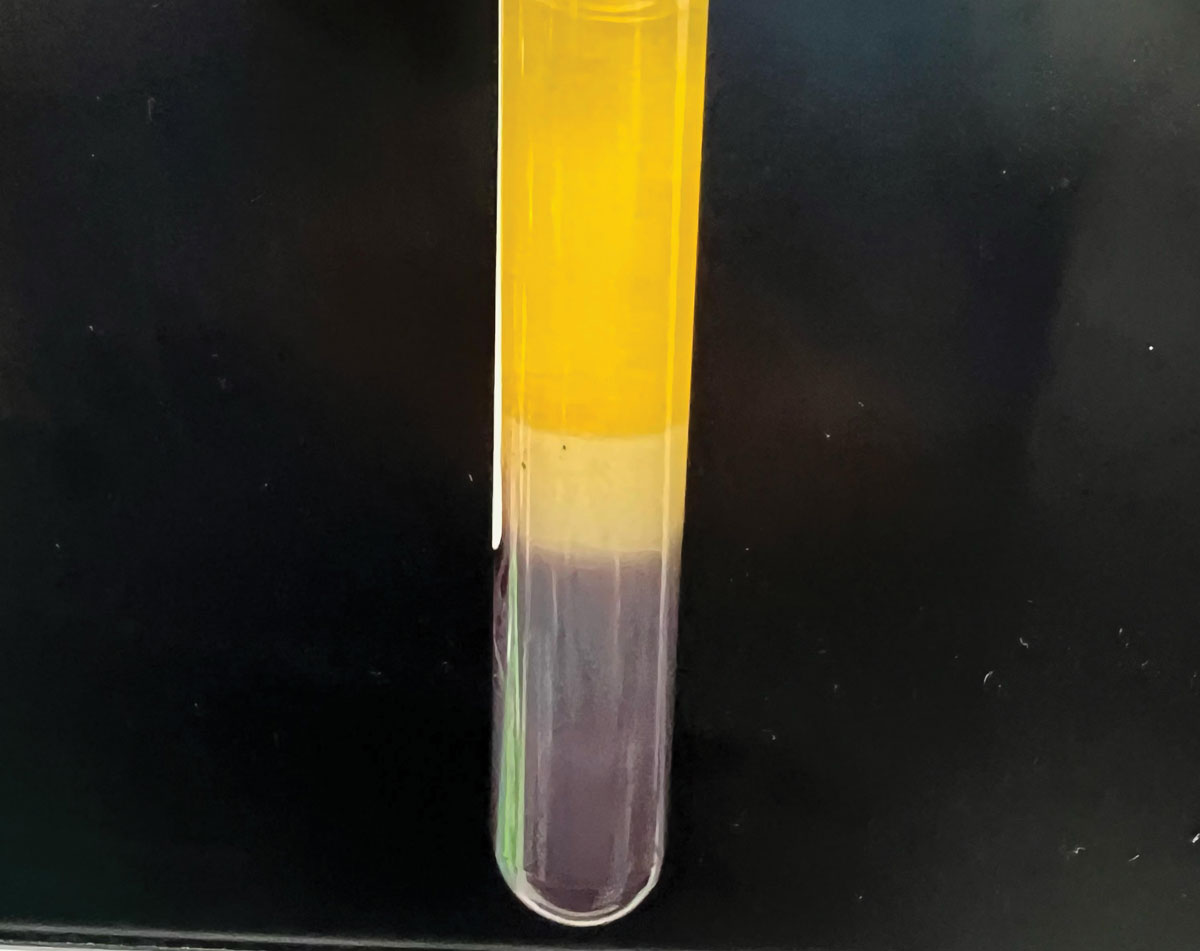

Typical batch of tiger tubes showcasing natural variation in color. Tubes are examined under a bright light to ensure quality of serum. Some tubes may not be used due to the visible presence of red blood cells in the serum layer (second tube from the right). Click image to enlarge. |

Gauge Success at Follow-ups

Setting realistic expectations with your patients and being open-minded to treatment plan modifications along their journey is imperative when dealing with chronic disease. Just as important is customizing their treatment plan to their specific needs, as well as being empathetic, as some patients usually have a lifelong battle with these conditions with expected flare-ups along the way. Although I’ve seen improvements in as little as two weeks after starting ASEDs, I inform them that it may take up to four to six weeks before we see significant clinical change, so I tend not to alter the dosage or concentration until they are seen at their progress visit.11,12 However, in my practice, I generally taper the dosage frequency and/or concentration over weeks to months if the patient’s condition shows significant improvement in signs and symptoms.

Although there appears to be no consensus for selecting an optimal concentration, most studies use 20% as it mimics the biological factors that are found in our tears.11 However, higher concentrations (up to 100%) have been used in other clinical studies.11 I typically start with a concentration of 40% but have prescribed above 50% in select patients, as most of my cases have responded well with 40%. I have personally found 40% to be a sweet spot as it allows for the patient’s supply to last about two months with a dosage of six times per day, reducing the number of trips for blood draws, while keeping a meaningful therapeutic concentration for most conditions. Also, dosing frequencies can vary considerably from three times a day to hourly, while six to eight times per day appears to be the most common.11,12

Obtaining both objective and subjective data at every visit is imperative for gauging treatment success versus failure. There are many symptom-based questionnaires that are efficient and cost-effective and help understand and track your patient’s subjective progress that is sometimes overlooked when we are clinically focused on objective improvements. I recommend using as many data points as possible, whether you’re using anterior segment photography to help the patient visualize their own progress or direct observation with vital dye staining (sodium fluorescein and/or lissamine green) to assess objective changes.

Other useful markers include conjunctival hyperemia scoring, ocular surface staining scores, osmolarity, TBUT and qualitative measures (MMP-9), or quantitative markers (phenol red threat test, Schirmer’s test) and visual acuity to track progress. Remember to always compare data points to a patient’s baseline (similar to visual field analyses in glaucoma management) and establish new baselines any time a new therapy is added to help guide your treatment. Serial photography helps visualize progress trends over time and has been beneficial in my clinic to pinpoint—and predict—the time of year that a patient usually experiences flare ups.

It is sometimes helpful to review and remove/replace an item from a patient’s existing complex regimen that does not provide a significant improvement to the disease process and/or the patient’s quality of life. However, some eyecare providers will prescribe topical steroids or other immunomodulators along with ASEDs for a synergistic effect, so discontinuation of their current regimen is not required.

Other Alternatives

One that should be considered if a patient experiences significant logistical or financial barriers, lack of therapeutic benefit or is unable to tolerate the treatment, including cryogenically preserved and dehydrated amniotic membrane grafts, scleral lenses, and other hemoderivatives such as allogenic serum drops, albumin drops and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) to name a few.

|

|

Close up of a discarded tube seen in the previous image (second from the right) with obvious red blood cells present in the serum layer, creating a non-uniform pink-red color. Click image to enlarge. |

A recent study compared the effect of 100% autologous serum to 100% PRP for the treatment of severe dry eye in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and found a similar statistically significant improvement in signs and symptoms; however, a greater reduction OSDI scores were observed in the PRP group.13 They found a reduction in OSDI scores in 100% of patients in the PRP group vs 77.3% in the autologous serum group compared to baseline. The authors believe that PRP, due to its concentration of platelets, has greater immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory components necessary in cell proliferation, wound healing and angiogenesis due to a larger amount of nerve growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor and fibronectin found in PRP than autologous serum.1 Despite this, there is limited data proving superiority of PRP to autologous serum, and comparative studies are challenging due to differences in blood preparation protocols, patient’s age, race, diet, dosage, instrumentation, patient selection, diagnosis, study size and duration to name a few.13

ASEDs play a critical role in OSD treatment and management and offer a significant improvement in a patient’s disease trajectory. With over 300 million people worldwide suffering from some degree of dry eye, incorporating this in your clinic can be the key factor in making a positive change in a patient’s quality of life.14 Although ASEDs are typically not a first-line therapy in many cases, I hope I demystified the common barriers and questions that exist surrounding the use of this so-called “big gun” that can lead to making this treatment a more accessible solution.

Special thanks to Joshua Keller, PharmD (Pharmacy Experience Manager) at Texas Star Pharmacy for assisting in this article.

1. Ralph RA, Doane MG, Dohlman CH. Clinical experience with a mobile ocular perfusion pump. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93(10):1039-43. 2. Davis A, Franco E, Nischal K, Halfpenny C. Autologous and allogenic serum tears. EyeWiki. Published December 8, 2022. Accessed September 10, 2023. eyewiki.aao.org/autologous_and_allogenic_serum_tears. 3. Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):575-628. 4. Shtein RM, Shen JF, Kuo AN, et al. Autologous serum-based eye drops for treatment of ocular surface disease. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(1):128-33. 5. Feroze KB, Patel BC. Neurotrophic keratitis. PubMed. Published 2022. Accessed July 1, 2022. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431106/. 6. Vazirani J, Sridhar U, Gokhale N, et al. Autologous serum eye drops in dry eye disease: preferred practice pattern guidelines. Ind J Ophthalmol. 2023;71(4):1357-63. 7. Wang L, Cao K, Wei Z, et al. Autologous serum eye drops versus artificial tear drops for dry eye disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ophthalmic Res. 2020;63(5):443-51. 8. von Hofsten J, Egardt M, Zetterberg M. The use of autologous serum for the treatment of ocular surface disease at a Swedish tertiary referral center. Int Med Case Rep J. 2016;9:47-54. 9. Aggarwal S, Kheirkhah A, Cavalcanti BM, et al. Autologous serum tears for treatment of photoallodynia in patients with corneal neuropathy: efficacy and evaluation with in vivo confocal microscopy. Ocul Surf. 2015;13(3):250-62. 10. Mondy P, Brama T, Fisher J, et al. Sustained benefits of autologous serum eye drops on self-reported ocular symptoms and vision-related quality of life in Australian patients with dry eye and corneal epithelial defects. Transfus Apher Sci. 2015;53(3):404-11. 11. Pan Q, Angelina A, Marrone M, et al. Autologous serum eye drops for dry eye. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2(2):CD009327. 12. Geerling G. Autologous serum eye drops for ocular surface disorders. Brit J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(11):1467-74. 13. Wróbel-Dudzińska D, Przekora A, Kazimierczak P, et al. The comparison between the composition of 100% autologous serum and 100% platelet-rich plasma eye drops and their impact on the treatment effectiveness of dry eye disease in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Clin Med. 2023; 12(9):3126. 14. Market Scope. 2016 Dry Eye Products Report: A Global Market Analysis for 2015 to 2021. St Louis: Market Scope; 2016. |