I’ve been known to get caught up singing to a good song in the car and miss a turn or two. Just one of these wrong turns can make an easy drive a lot more frustrating. Some of our contact lens patients may know the feeling, as they find themselves heading down the road toward contact lens dropout.

While ranges vary, research shows up to half of new contact lens wearers drop out within the first three years.1 Myriad complications can lead to drop out, but a lack of patient education, a compromised ocular surface and the wrong lens design are the big three I’ve noticed. Here’s how you can identify a potential problem before it leads your patients down the road to dropout—and how to steer them toward the path of success.

Invest the Time

Many patients drop out of contact lens wear because of a miscommunication or lack of communication somewhere along the way, especially at the outset. In practice, contact lens fittings add time to the exam, even when everything runs smoothly. It’s tempting to save a few minutes by skipping or delegating patient education about different aspects of the lens design, materials and expectations. However, this costs much more than just a few minutes of your time in the long run, and it dismisses an opportunity to connect with the patients and understand their visual needs. Instead, clinicians can focus on three main categories during the fitting and education process: motivation, goals and expectations.

Motivation. This reflects strongly on the patient’s chance for success. It’s obvious when a patient is highly motivated. They are typically the patients that cram the lens between their lids during insertion and removal training. They have a good idea about contact lens use from self-driven research and show a willingness to heed professional direction. Highly motivated patients are often more attentive during the training process, more interested in new fit instructions and are generally in a better position for long-term success. Motivation is especially important with potentially tricky toric and multifocal fits.

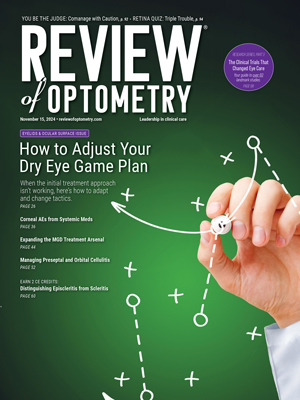

|

| Uncovering poor tear film stability caused by meibomian gland dysfunction, which results in the lipid layer thinning (arrow), can help you treat patients before they struggle with contact lens wear. Photo by Dan Fuller, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Goals. Patients ready for contact lens wear understand and have thought about what they want from their lenses. They’ve talked to contact lens wearing friends and have their own goals. They will be prepared to answer questions such as:

- Are you going to wear these full time or will these be reserved for certain activities?

- Do you value distance vision over near vision?

- Are you prepared for the hygiene requirements?

- What is the working distance of your computer?

It’s crucial that you ask these questions to better understand the patient’s visual goals, which will guide the fitting process. The majority of the contact lens fit is not about the actual fit—it’s about understanding the patient and why you are fitting the lenses in the first place.

Expectations. The motivated patient with specific goals likely has equally specific expectations. The road to dropout is paved with mismatches between patient expectations and the reality of what current soft lenses can offer. It’s your responsibility to bridge the gap, and nothing does this better than honesty.

For example, consider a new wearer with -0.75D cylinder or an oblique axis. I always let them know first that they will see better out of their glasses than their contact lenses and why. I never hide the fact that they will have visual fluctuations. These situations can be delicate, and you can put the patient on the road to success if they are first prepared for these discrepancies.

The same goes for established wearers when their prescription changes, whether they now need toric, multifocal or monovision. Optics are complex but highly effective within a multifocal lens and the more the patient knows, the more likely they are to accept the lenses’ benefits and limitations.2

Use visual aids such as clinical images and the fitting guide to demonstrate the potential limitations in their vision to prepare them for any differences while wearing these designs. The use of loose lenses in the office for a monovision fit helps determine dominance and acceptance of the setup and shows the patient what to expect.

Never let the time required to show and tell patients about that which you are an expert deter you from offering them what you know can best suit their visual needs. If you invest the time, they will perceive the value, appreciate your attention and will be less likely to drop out of contact lens wear.

Set the patient up for success by telling them up front what to expect with any change and focus on the visual enhancements. Avoid words such as “sacrifices” or “compromises” and instead remind them what there is to gain.

Dry But DeterminedA patient presented who had discontinued contact lens wear secondary to dry eye. She was 21 and had previously been prescribed Restasis (Allergan) but was using is as needed, mistaking it for an artificial tear. A chart review revealed that she had tried almost every lens available that was appropriate for her —in total, about eight different lenses. She was wearing none of them when I talked with her. At this visit, she said she was frustrated but not quite ready to give up. I reviewed the importance of Restasis as a medication, its dosing and its role in her contact lens life. With new understanding, she agreed to be adherent to the prescription and return in three months for her contact lens fit. She left happy, hopeful she would likely be able to wear any of the previously fit lenses once the ocular surface was healed and she was not “out of options.” |

Look First

Introducing a foreign object to the ocular surface is “intrinsically” inflammatory.3 The natural protective process of inflammation (as when something is foreign in the body) can go awry by adding a contact lens to the ocular surface. The presence of soft contact lenses can increase the presence of inflammatory cells, causing the classic signs of redness, pain and swelling, as well as alter tear film osmolarity causing ocular surface discomfort and dryness.4,5 When pre-existing ocular surface issues are ignored prior to lens introduction, the chance of dropout increases considerably.

One of the leading culprits of contact lens discomfort and dropout is dry eye disease.6 In combating this, we must be proficient at identifying the presence of dry eye and treating it appropriately.

When I have a new wearer, one of the first things I do is reach for my slit lamp. This enforces the priority I put on their ocular health as a precursor and requirement of successful lens wear. I want to make sure that the ocular surface is ready to accept a contact lens—something I am sure to communicate with the patient.

I start with a tear film assessment with and without fluorescein, not in combination with a numbing agent, as a thick drop that can mask tear film characteristics.7 I also perform a lid and lash assessment and document any signs and symptoms. The efficacy of the blink, the natural blink rate and the tear break-up time are all important factors, as is a gross assessment of meibomian gland status and any signs of anterior blepharitis. Ask the patient to describe how their eyes feel, being careful not to prompt them.

When preparing the eye for the introduction of a contact lens, clinicians should focus on quantification rather than qualification to accurately measure improvement with treatment and determine an appropriate timeline for lens introduction. Metrics such as tear break-up time and Schirmer testing are valuable.8 A patient with a normal ocular surface and, in my opinion, ready for contact lenses would have a tear break-up time of approximately 10 seconds and a Schirmer score of at least 10mm after five minutes.9,10

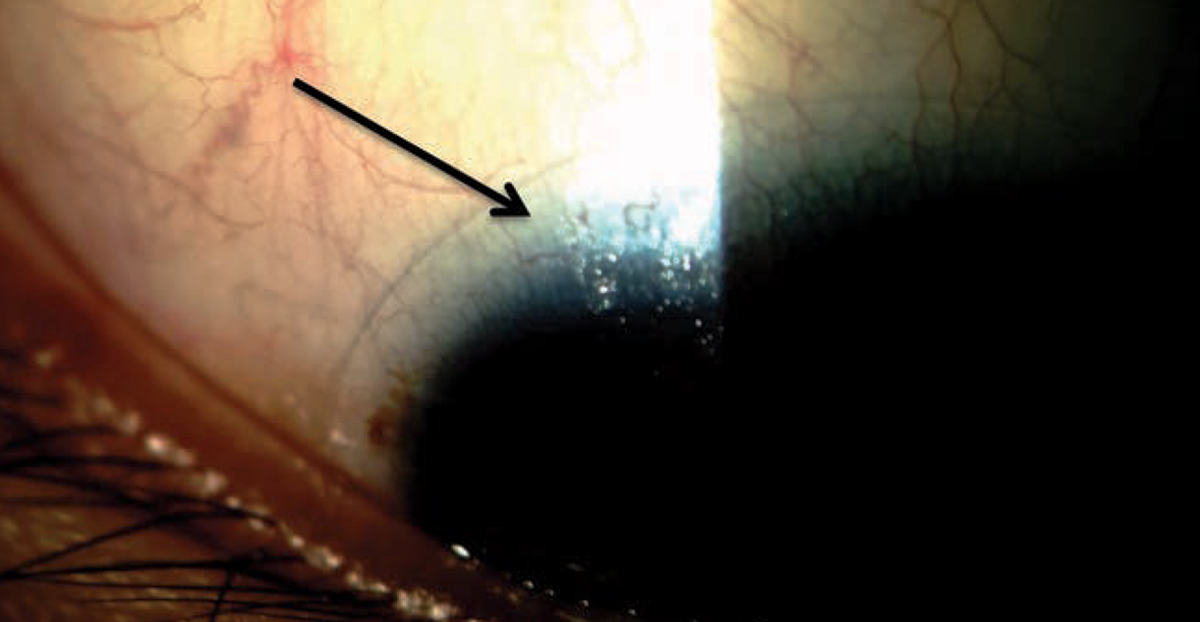

|

| Patients who have a history of a corneal ulcer, such as this one with a Pseudomonas ulcer, may do better with a daily disposable lens option—and plenty of patient education on proper lens wear and care. Photo by Christine W. Sindt, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

For patients diagnosed with dry eye and not ready for contact lens wear, I usually prescribe an aggressive dose (consistent and frequent) of over-the-counter artificial tears, preferably using a preservative-free version, in combination with warming masks twice a day. In cases where the dry eye is significant and mostly aqueous deficient, I prescribe a cyclosporin in addition to the lubricant.11 I bring them back to assess the ocular surface as frequently as needed until it is healed.

In a world of instant gratification, it can be hard to get the patient on board with forgoing contact lens wear until any underlying ocular surface issues are addressed. However, most patients seem to appreciate when you go the extra mile to make sure they are successful, especially highly motivated patients or those who have had negative experiences in the past.

Unless you are routinely performing a dry eye workup, you are likely allowing these patients to zoom right past you. You can rectify this by asking established wearers what you can do to make their contact lens experience better or if they wished something could be improved with their contact lenses rather than the typical “how are your lenses working?” which will often elicit a vague, “fine, thanks.”

When asked differently, they almost always mention something about end-of-day comfort. In most cases, this is, in part, related to a dry ocular surface. You can reassure them that a motivated dry eye patient is not excluded from contact lens wear and relief can be as simple as changing materials or modalities. One study suggests the use of low-water content lenses such as silicone hydrogels reduce tear film deposition on the lens surface, optimizing lens wettability and tear film stability, ultimately improving comfort.6 Although not as easily quantifiable, patient comfort truly is the bottom line in preventing dropout.

Furthermore, the modest use of rewetting drops should not be shrouded in a negative cloud; it’s not a sign of contact lens wear failure. When you consider the environment in which we live and work, rewetting drops should be an expected part of contact lens wear. A change to a more dry eye-friendly material and establishing rewetting drop use as a norm for your patients could ultimately decrease drop out.

Taking action on their behalf will allow your patients to feel heard and understood, which will build their trust in you. When they are comfortable, they are more likely to open up when you ask them how you can improve their contact lens life year after year, perpetuating continued wear.

Find the Best Route

Knowing the various lens designs and modalities is important when patients are about to undergo a change in their lenses. Patients may prompt a change on their own or, more often, a change will be practitioner led for various reasons. Some of these include convenience, reduced over-wear potential, comfort, improved vision, freedom from glasses and improved overall ocular health. Established wearers usually change in one of two ways:

Change in modality (e.g., extended wear modalities to a daily disposable option)

Lens design change (e.g., toric or multifocal/monovision)

Change can be challenging, plain and simple. In all cases, the situation needs to be handled with care. Recognizing the switch as a potential change in their daily life and finances and showing that you understand this will strengthen trust, ultimately decreasing the chance the patient will drop out of contact lens wear after the switch. Be careful to reiterate and demonstrate the benefits that prompted the change instead of potential compromises.

Making a good first impression with the new lens is important and requires a good working knowledge of the options on the market:

Parameters: It’s tough to backpedal from a ten-minute conversation focused on a daily lens when you later find out that it does not come in the patient’s oblique axis.

Materials. Several “workhorse” daily lenses you likely have in your trial set are actually high water content, non-silicone hydrogel materials, which may not be ideal for dry eye patients who may currently be in an extended wear lens.

Designs. Be creative with multifocal and monovision fits. Understand designs such as aspheric and distance/near center and be willing to use a modified version to meet your patient’s goals. For distance centric patients, you may need to have a designated distance center (in one eye or both) and knowledge of which lenses provide this will help ensure a good first impression.

Furthermore, do not limit your knowledge to the trials you have in your office. While these will always be your go-to options (consider stocking a variety of designs and materials), another lens might be the best option for a patient, and you should be prepared to know what it is and offer it to them.

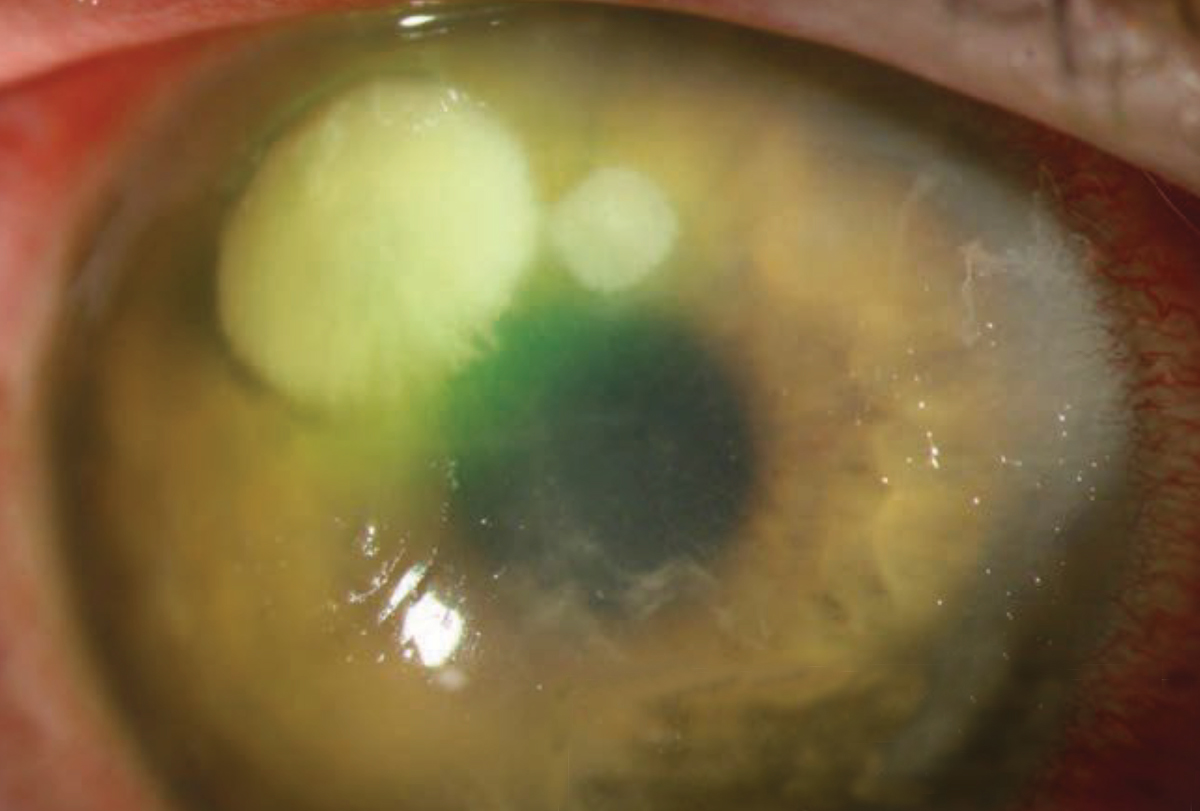

|

| Patients with inferior corneal staining secondary to lagophthalmos, as seen here, may struggle with contact lens wear if it’s not addressed first. Photo by Paul M. Karpecki, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Get Back on Track

The rest of the world remains a few steps ahead of the United States, with access to protocols that allow transepithelial (or ‘epi-on’) CXL, accelerated CXL (which delivers higher doses of UV over a shorter time period) and other already well-known procedure options. But these are most likely headed to our shores eventually. “Now that epi-off CXL study data is well-established, many clinical trials are investigating the comparative treatment efficacy of different delivery protocols with the purpose of improving the overall patient experience,” Dr. Chang notes.

Here’s a quick look at each:

Epi-on. One study found that an investigational crosslinking protocol avoiding epithelium removal can safely stop disease progression in corneas as thin as 302nm and may offer faster visual recovery than other methods. The researchers used a new riboflavin formulation and application technique and a pulsed dosing of UVA to allow better oxygen transmission into the cornea.

They observed improvements in uncorrected and corrected distance visual acuities (DVA), total higher-order aberrations and coma and maximum keratometry values. There was no progression or loss of effect, nor did the team note any complications. Participants were only uncomfortable for 24 hours post-op, with blurred vision lasting two to three days and contact lens wear resuming within a week.5

Also looking into oxygen flow—this time for the epi-off technique—a team found that increasing oxygen concentration around the cornea during UVA radiation can improve the efficacy of conventional CXL.6

Accelerated. Other studies are looking into protocols employing a stronger UV light for less overall treatment time. Conventional CXL uses 3mW/cm for 30 minutes, while research into the accelerated technique documents anywhere from 9mW/cm for 10 minutes to 30mW/cm for four minutes.7 Investigators found that both accelerated protocols and conventional CXL had similar visual acuities, refractive outcomes and stabilization rates, although more parameters showed significant improvements 12 months after the standard protocol. While their results are promising, they also indicate the need for a better understanding of the effects of accelerated CXL.7

Around the same time, another team confirmed that accelerated CXL is a contender for keratoconus treatment, finding that the technique can safely halt progression within 24 months.8 After two years of follow-up, they observed an increase in the number of eyes with a corrected DVA of 0.3logMAR and a significant reduction in maximum and mean keratometry values.8 Other researchers demonstrated that the accelerated procedure is also associated with less corneal haze and a smaller risk of continuous flattening.9

A new method known as custom fast CXL does not disrupt the epithelium and features 15 minutes of corneal presoaking with a riboflavin-vitamin E solution and a 370nm UVA radiation beam centered on the most highly curved region of the cornea. The study noted “a significant, rapid and lasting cone progression stoppage, astigmatism reduction and visual acuity improvement.”10

Accelerated CXL may also aid in keratitis therapy. Researchers have recommended a technique called photoactivated chromophore for keratitis (PACK) CXL to treat moderate-sized, therapy-resistant bacterial corneal ulcers.11 The same reactive oxygen species that create new covalent bonds within the stroma have the added benefit of killing pathogens in the treated area; also, the stronger cornea is more resilient against pathogenic attack.

Another group of investigators provided further support for adjuvant PACK-CXL, finding that the procedure can expedite the resolution of infectious keratitis with bacterial or fungal etiologies by reducing healing time and infiltrate size.12 PACK-CXL’s usefulness may extend to fungal keratitis treatment as well, especially when combined with voriconazole therapy, a different study proposed.13

Combinations. Accelerated CXL may not provide any added benefits when combined with LASIK, though. A team looking into the efficacy of combining the two did not find any difference between the combination procedure and conventional LASIK in uncorrected DVA or refractive stability.14

Other simultaneous procedures involve CXL and corneal rings or photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). These may present effective options for keratoconus and other corneal ectasias, researchers suggest. They found that the changes in corrected and uncorrected DVA and maximum keratometry values were significant for both combinations. The team concluded that combined CXL and ring implantation may be more effective for eyes with irregular astigmatism and worse corrected DVA, while CXL and PRK may be more useful for eyes with irregular astigmatism but better corrected DVA.15

Another study looking into CXL combined with topography-guided PRK warned against the swift adoption of this procedure for keratoconus after observing various complications and continuous progression post-op. Adverse events included corneal haze, primary herpes simplex keratitis, persistent epithelial defects and central corneal stromal opacity. Related to removal of the epithelium were post-op pain, photophobia, lacrimation, foreign body sensation and healing difficulties.16

Patients who are considering dropping out or who have already done so aren’t lost. Getting them back on track will be challenging, but possible. In my experience, after an initial episode of contact lens dropout, patients often develop a negative attitude toward lens wear. Two recurring statements I often hear my patients make are:

“I can’t wear contact lenses.” Many patients seem to think “contacts don’t come in bifocals” or they “have the ‘stigma’.” This vague, defeated tone is an excellent opportunity for intervention, and I greet their disbelief with a “challenge accepted” mindset. With the wide range of parameters, materials and modalities we have at our disposal, almost anyone can be a successful contact lens wearer. With proper communication and a good fit, those previously fallen from contact lens wear can be reclaimed.

“I’ve had an ulcer in the past, so I cannot wear them again.” I don’t push a patient to try lenses again if they have any sense of dread or fear. In addition, I will refit this patient only if they are motivated and agree to adhere to prescribed lens wear habits and hygiene. If I sense they want a second chance, I offer daily disposables and explain that this would likely be their only option going forward. Most patients value the health of their eyes and my recommendation rather than pushing back on this stipulation.

With proper patient education, we can help restore confidence in these patients and get them back into their lenses. Some of my happiest patients are the ones who return to contact lens wear after thinking they were the exception.

Our role as optometrists is to make sure we are providing the best vision correction options to help our patients meet their goals. For many, contact lenses provide the freedom they want and the practice boost you need. Contact lenses have the power to solve many of our patient’s problems and help them meet their visual goals in a way that could significantly impact their lives.

Dr. Tompkins is a former assistant professor at Southern College of Optometry in Memphis. She most recently worked for Indian Health Service in Fairbanks, AK, and surrounding villages and works part-time at Church Health in Memphis. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Optometry.

1. Markoulli M, Kolanu S. Contact lens wear and dry eyes: challenges and solutions. Clin Optom. 2017;9:41-48. 2. Pérez-Prados R, Piñero DP, Pérez-Cambrodí RJ, et al. Soft multifocal simultaneous image contact lenses: a review. Clin Exp Optom. 2017;100(2):107-127. 3. Efron N. Contact lens wear is intrinsically inflammatory. Clin Exp Optom. 2017;100:3-19. 4. Sindt CW, Grout TK, Critser DB, et al. Dendritic immune cell densities in the central cornea associated with soft contact lens types and lens care solution types: a pilot study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:511-19. 5. Zhang X, Jeyalatha VM, Qu Y, et al. Dry Eye Management: Targeting the Ocular Surface Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1398. 6. Ramamoorthy P, Sinnott LT, Jason J Nichols JJ. Contact lens material characteristics associated with hydrogel lens dehydration. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2010;30(2):160-6. 7. Muntz A, Subbaraman LN, Luigina Sorbara, et al. Tear exchange and contact lenses: a review. J Optom. 2015;8(1):2-11. 8. Lubis RR, Gultom MTH. The correlation between daily lens wear duration and dry eye syndrome. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(5):829-34. 9. Pflugfelder SC, Tseng SC, Sanabria O, et al. Evaluation of subjective assessments and objective diagnostic tests for diagnosing tear-film disorders known to cause ocular irritation. Cornea. 1998;17(1):38-56. 10. Milner MS, Beckman KA, Luchs JI, et al. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: dry eye disease and associated tear film disorders - new strategies for diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28(Suppl 1):3-47. 11. Perry H, Donnenfeld E. Topical 0.05% cyclosporin in the treatment of dry eye. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(10):2099-107. |