Transformative TechOptometrists today have more tools than ever at their disposal to help detect, treat and manage disease. To help you keep up with the constant innovation, the September 2024 issue of Review of Optometry—our 47th annual technology report—reviews the pros and cons of telehealth in optometry, new devices in eye care and the future of remote monitoring. Plus, find the results of our annual tech survey to discover which clinical instruments your peers are buying or desiring. Check out the other articles featured in this issue: |

Optometry continues to transform, driven by scope expansion and technological advances. While increased scope is consciously chosen by the profession’s advocates as a goal and pursued with intent, technological change is a mixed bag that includes some elements we actively embrace and others that are beyond our control or, indeed, wishes. New telehealth technologies employed by online retailers, including those accessible on a smartphone, enable consumers to self-administer Rx fulfillment and renewal, diminishing the traditional role of ODs while skirting statutes and regulations intended to protect the public. At the same time, more eye doctors are wondering if these same technologies can better serve their patients.

Below, we explore the impact of these developments, offering our own opinions on many contentious issues; other optometrists will have different perspectives. Refraction and vision correction are central to optometry and there’s justifiable reluctance to relinquish them, especially to lesser modalities where patient care might suffer. Our hope is to stimulate discussion and a reckoning, both individually and collectively, with ongoing changes that will continue whether we want them to or not.

Online Vision Service Currently is Rx Duplication

Unlike dentistry, where hands-on procedures are a mainstay, optometry possesses a greater proportion of hands-off services, which positions optometry for greater (but not limitless) opportunities to adopt telehealth services and self-administered measurements. An obvious constraint with remote digital services is the need for the patient to be seated alongside the measurement device.

The appeal of smartphone-based service is that most of the population already owns a smartphone, whereas measurement with specialized larger instruments requires their co-location with the patient. Smartphone adapters such as Netra (EyeNetra) and Insight (EyeQue), where mobile service is enabled, may bridge the gap, or these adapters may be delivered to the patient for self-administration. Once the clinical data (refraction and imaging) is collected, it is reviewable by a doctor at a different location and time.

The constraint to online retailers is their need for a valid prescription to sell product. Hence, they desire to generate their own eyeglass and contact lens prescriptions, even if these are duplications of expired Rxs. Most of today’s “online eye exams” embraced by these retailers are built around duplicating prior prescriptions. A remote doctor signs a duplicating script if the patient demonstrates reasonable self-administered visual acuity (VA) and attests that they are not at high risk for eye disease and they are not experiencing unusual symptoms. These online questionnaires are supposed to prevent users with significant risk factors or eye disease from renewing prescriptions, but they can be easily gamed: the user merely clicks the back-button to answer the same question differently to pass validation.1 These questionnaires to elicit self-reported vision problems are already suspect, as even the same questions presented in a different order can yield a different prevalence of vision problems.2

The looming prospect is for self-administered de novo smartphone-based refraction. Meanwhile, de novo remote refraction today is performed with technologies like 20/20Now (20/20 Vision Center) and DigitalOptometrics (Figure 1), where specialized equipment is placed inside a standalone location so that eyeglass prescriptions are generated without a doctor physically present.

|

|

Fig. 1. A range of telehealth options exists currently. Some providers employ specialized equipment in a standalone location to allow direct examination of the patient while the OD is remote. Click image to enlarge. |

Consumers Mistake VA and Refraction

In the same manner that the lay public confuses optometrists, ophthalmologists and opticians, consumer confusion abounds between VA and refraction; the public does not appear to understand that these two measurements are different and that whether taken separately or together, they do not constitute a complete eye exam. They are, of course, separate components of an eye exam used by a doctor in clinical decision-making. Online retailers, however, are doing vision screenings and labeling them as “exams,” further confounding the definition with consumers. Perhaps one solution would be a regulatory requirement for a service to qualify as an “eye exam” in the same manner that “organic” is a legal term and a “Realtor” is a special designation obtained by some real estate agents.

Online prescription services today concentrate on self-administered VA, with the apparent unintended effect of mistakenly leading consumers to believe that VA is a substitute for refraction. It is possible that some even believe that VA testing is a comprehensive eye examination. This may explain fallacious patient comments like, “I’m 20/20 so nothing is wrong.” The mistaken narrative that prescription services are “eye examinations” diminishes the consumer’s perceived value of an actual comprehensive eye and vision exam conducted in an office. The burden of educating the public and correcting misunderstandings is imposed on our profession and our industry partners. Doing so is no easy task, given a plethora of noisy messages competing for each consumer’s limited attention and their inherent desire for a simplified experience enabled by digital alternatives to traditional in-person services.

When is Refraction a Prescription?

Experienced optometrists do not always prescribe their subjective refraction for eyeglasses. Instead, they may modify the prescription to attenuate the patient’s adjustment by decreasing the magnitude of oblique cylinder or skewing the prescription closer to their habitual correction. Other factors including binocular status, accommodative reserve, eye dominance, level of anisometropia, vocational and lifestyle demands, historical correction and personality can collectively influence the doctor’s prescription. In effect, two patients with identical refractions may need different eyeglass prescriptions.

As an example, the primary eyeglass prescription for a presbyopic software engineer may be a near-variable focus lens design, whereas the priority for an airline pilot may be single vision distance glasses or even double D bifocal lenses. It is understandable how a patient with difficulty adapting to new glasses who makes a comment like, “My doctor gave me the wrong prescription and it made my stigmatism worse,” may find it appealing to take a do-it-yourself approach. Contrary to the consumer notion that there is only one correct prescription, there is a range of acceptable prescriptions and the practitioner’s judgement is valuable in guiding the patient to a desirable outcome.

If self-administered refraction becomes more of a reality, should refraction alone drive eyeglass fulfillment? If so, the dystopian optometric future is one with no need for an eye doctor to create a prescription or validate and modify a refraction outcome. In theory, artificial intelligence could be trained to understand how doctors modify eyeglass prescriptions to facilitate patient satisfaction.

Until such methods prove themselves equal to human intellect and empathy, it would seem prudent that doctors still maintain prescriptive authority to modify their refraction. It is an ideal time for our profession to guard against the negative consequences of this potential future, especially as the segregation of refraction from a comprehensive eye exam would surely diminish patient care. Meanwhile, the current hybrid model of an off-site doctor remotely operating the phoropter with assistance from ancillary staff, while less than ideal, still allows for a clinician to make judgements in modifying the refraction outcome for the resulting prescription.

It is noteworthy that most of today’s electronic medical records by default populate the refraction outcome into the fields for the eyeglass prescription. Practitioners still reserve the authority to modify the prescription for eyeglasses according to their judgement. Unfortunately, most consumers are unaware that the refraction outcome is not necessarily what is prescribed. Without this awareness, there is an inherent tendency for consumers to undervalue the role of clinical judgement in eyeglass prescribing.

Some eyecare professionals feel that autorefraction is not sufficient enough to prescribe glasses. We interpret this to mean that their final eyeglass prescription frequently and noticeably deviates from autorefraction. Historically, one definition of a subjective refraction was the most plus (or least minus) spherical value with full cylinder and respective axis to yield the best VA. However, for non-presbyopes, the prescription frequently has less plus or more minus spherical power than the refraction.

Over 30 years ago, one study discussed the repeatability of measurement of the ocular components. Of note, the limits of agreement for 95% confidence of two non-cycloplegic subjective refractions of the same eyes was found to be ±0.63D.3 This means that to have 95% confidence that the difference between two refractions is real, the difference must be at least 0.63D. One conclusion from this is that subjective manifest refractions appear to lack the precision that our colleagues assign to their subjective refraction results.3 Subsequent clinical investigations of the agreement limits of autorefractors find values that are significantly smaller.4-6 The suggestion is that autorefraction is more repeatable than subjective refraction performed by clinicians. Nonetheless, the authors hold that an autorefraction is one component that drives determination of the eyeglass prescription and is not necessarily the same as the eyeglass prescription.

Self-refraction, Today and Tomorrow

The trajectory of technological advances suggests we could see a viable self-refraction soon. Most optometrists may bristle at this notion, since refraction is the historical foundation and economic driver of our profession. While refraction can, in certain instances, be a component of systemic or ocular disease detection, is that enough reason to make self-refraction available only under the supervision of a licensed professional? Some ODs will surely say yes, while others will demur.

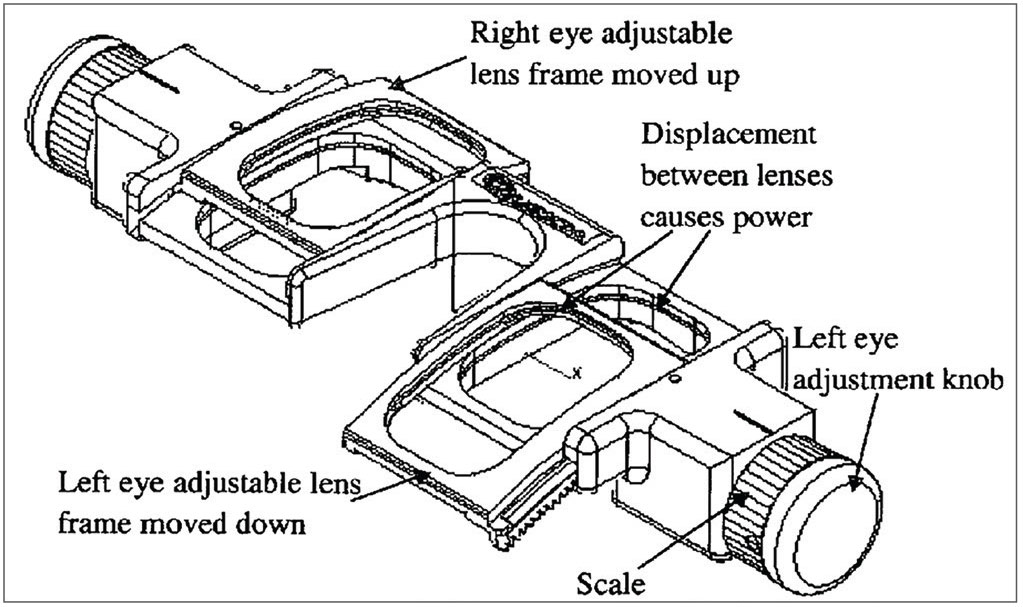

Self-refraction is arguably already crudely available. Consumers can select over-the-counter readers intended for presbyopia at retail outlets or online; a consumer with pre-presbyopic hyperopia can do the same. Minus-powered glasses are ubiquitously available on online retailers like Amazon, allowing consumers to select and purchase them without an eyeglass prescription. Consumers can even purchase their own trial lens set online (Figure 2) or lens bars and refract themselves, though this would be an unlikely scenario. The US patent application 2014/0176909 by Spivey and Dreher (Figure 3) illustrates an Alvarez plate self-refractor where two adaptive optical components slide against each other to produce a continuum of sphere, cylinder and axis lens powers.7 Alvarez plates were also the basis of adjustable-focus eyewear.8 Adjustable-focus Alvarez plate eyewear are available through various online retailers like Amazon along with one company in the UK named Eyejusters.

|

|

Fig. 2. Trial lens sets available for online purchase without a professional license. Click image to enlarge. |

Is the greater public good better served by keeping refraction and eyeglass prescribing controlled only by eye doctors? A fundamental question is whether self-selection of lens power significantly risks injury or harm to consumers. So far, there is scant data supporting this concept from countries where prescriptions are not needed for eyewear purchase. Perhaps the more pressing issue is helping consumers understand the value of a comprehensive examination vs. believing that VA and refraction are all that is needed for their vision care. Far too many laypeople believe the only reason to see an eyecare professional is to get an eyeglass Rx.

|

|

Fig. 3. Alvarez plate self-refraction device (Spivey and Dreher). Click image to enlarge. |

Will Glasses and Contact Lenses Go Over the Counter?

Should eyewear orders continue to require a prescription in the US? In many other countries, purchasing eyeglasses and contact lenses does not require a prescription, which prompts the question of whether the US should follow suit. After all, consumers are allowed to measure or select their own anatomic dimensions for hats, clothing, shoes, rings and other personal items. They can measure their own blood sugar, blood pressure, pulse, temperature and other vital signs; they can administer their own pregnancy tests and COVID tests and they inject their own insulin. As of October 17, 2022, most consumers can purchase over-the-counter hearing aids.9 People are free to pierce and tattoo their own bodies and YouTube videos abound on how to fix a dislocated shoulder yourself. It is natural for consumers to wonder why a prescription is needed to order spectacle eyewear. It is incumbent upon our profession to give them a compelling answer.

Most eye doctors, including us, believe patients are still best served by spectacles and contact lenses requiring a prescription; this is because the modification of the refraction based on their unique lifestyle visual demands and their binocular vision factors optimizes visual performance and aspects of their quality of life. There is also value in refractive data signifying potential eye disease. For example, fluctuating refractive error could indicate systemic blood sugar anomalies; a unilateral myopic shift in one eye can signify a developing nuclear cataract; a soft refraction endpoint with high oblique cylinder may indicate elevated higher-order aberrations and keratoconus. The refractive state of the patient is just one way we are alerted to their ocular and systemic health; direct examination yields countless more opportunities that would be lost in a move to online fulfillment.

Nevertheless, remote and “do-it-yourself” eye care can expand access to vision correction and eyewear. These newer methods of service also reveal different levels of eye care: some consumers are content with “good enough” and prioritize minimal spending for their eyewear, while others who want greater accuracy, precision and an elevated overall experience will seek out a licensed eyecare practitioner. Increasing emphasis on ocular disease in the optometric curriculum may unintentionally trivialize the importance of refraction and the art and science of prescribing eyewear. The expanding scope of optometry may be associated with a concomitantly lower interest in refraction and optical fulfillment. Some ODs are indeed less interested in eyewear prescribing and increasingly resigned to the growth of retail fulfillment and efficacy of online vision testing. We believe the fate of refractive prescriptive authority in the US depends on the attitudes and practice patterns of optometrists, as it will influence how far online retailers get toward selling glasses and contacts without prescriptions. Can we thread the needle of allowing online refraction and Rx fulfillment without degrading or marginalizing the comprehensive eye exam? Time will tell.

Telehealth and Optometry

Optometry is well-positioned for telehealth with ever-improving technology for digital image and data gathering by ancillary personnel and by patient self-administration. The highest calling of a licensed optometrist is not data collection and making measurements but rather diagnosis, treatment and consultation. We believe the systematic approach to case history and data collection, including refraction, biomicroscopy and retinal imaging, enables the remote practitioner to diagnose, treat and consult. Technology in development for tele-optometry may support eyecare delivery that surpasses the ability of current office-based systems, at least in terms of access and convenience, such as with the capability to allow for data-driven diagnosis and to provide the practitioner flexibility to remotely care for patients.

Still, one can’t help but feel that telehealth diminishes important parts of the patient care encounter. Body language, eye contact and vocal tone—all facilitators of empathy and connection—just don’t land the same way through a computer screen. Tele-optometry protocols should be developed with such trade-offs in mind and include efforts to preserve the doctor-patient relationship, such as an annual in-person visit with telehealth offered as a supplementary role throughout the year.

Cost containment is a major influence in health care. Expenditures continue to increase disproportionate to growth of the US GDP.10,11 Cost-cutting comes with the objective of not compromising the quality or efficacy of care. Increased doctor productivity and reduced costs are major factors in profitability. The key question regarding telehealth is whether it maintains efficacy while achieving greater efficiency and productivity.

Trends often fall into “supply-push” or “demand-pull” forces. The demand-pull forces include a shortage of optometrists in some markets along with a concomitant expansion of eyecare outlets by some aggregate eyecare providers. This reality is particularly apparent in the UK and Europe, where stores without an eye doctor are called “dark stores.” The corporations owning these dark stores are eager to employ technology for remote care, as the growth in new stores opening outpaces the number of eyecare professionals seeking employment there. In this case, the demand for eyecare professionals cannot be met. At the same time, there is a supply-push force manifest in the strategy of opening new outlets and providing eyewear at lower price points to reach new markets.

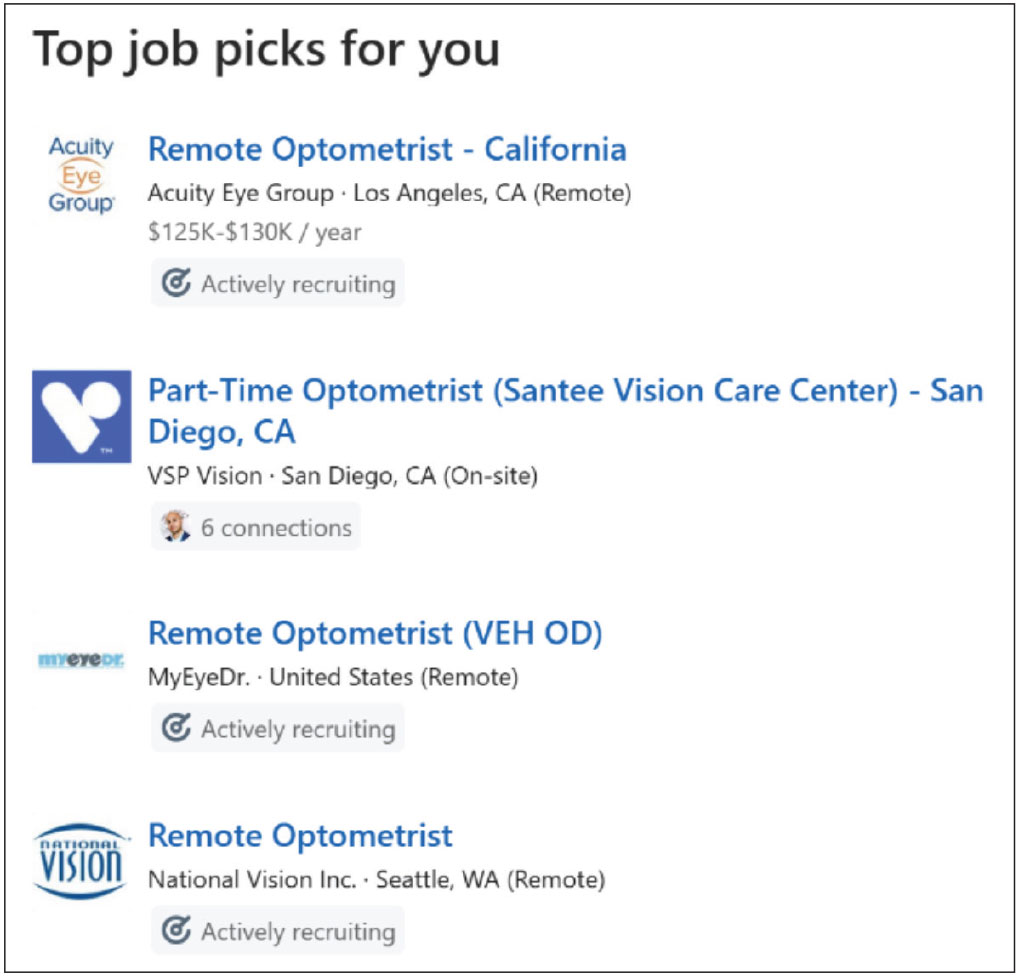

The growth of private equity–backed practice groups and other large aggregate vision care delivery entities in the US is already driving telehealth adoption in eye care (Figure 4). These entities must grow to complete their ultimate exit goals or shareholder value, respectively. We forecast that private equity–owned groups have reached or will reach a point where they no longer need to purchase practices. As they build their individual brands, they may open new practices instead of purchasing existing ones. The cost to open and market a practice may be less than purchasing a practice that generates similar revenue.

|

|

Fig. 4. LinkedIn remote employment opportunities for ODs. Click image to enlarge. |

The missing element is the eyecare practitioner. Private equity–backed eyecare networks lose more than a few former-owner optometrists when their retainer period ends. If the number is significant, it portends a relative shortage of corporate ODs. The financial incentives for private equity networks appear to be manifest in the reduction in practitioner chair time per patient to increase patient volume, while concurrently reducing staffing costs. Remote telehealth models may help meet these objectives.

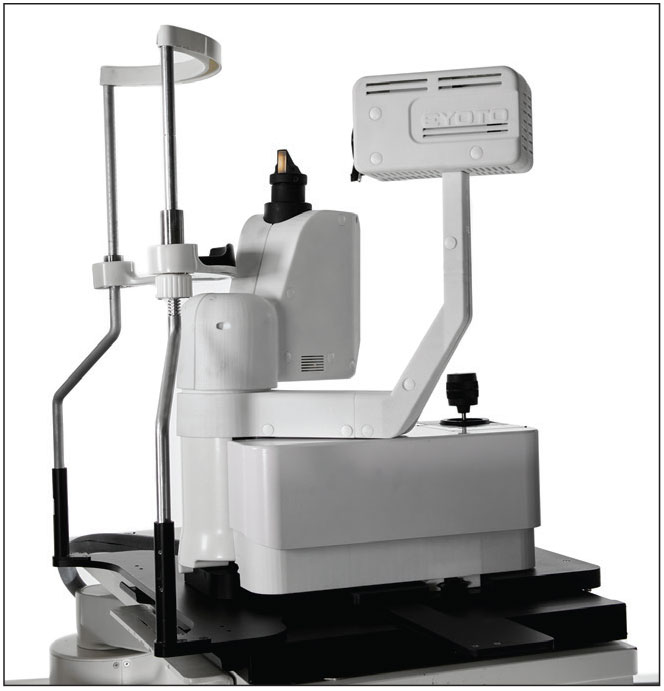

Dark stores and the desire for increased productivity appear to support instrument companies like Topcon, Zeiss, Eyoto and others that are developing telehealth technology and instrument suites (Figure 5).12-15 These instrument companies may be responding to a more global demand rather than perceived eyecare provider demand. At least one national retailer adopted using remote eye doctors to perform eye exams systematically.16 However, this remote approach was heavily criticized by the American Optometric Association (AOA) before the COVID lockdown.17 The retailer still appears to operate using this model.

|

|

Fig. 5. Commercially available, remotely operated slit lamp. Photo: Eyoto. Click image to enlarge. |

Consumer-driven Online Care: Smartphone Today, Smartglasses and Headsets Tomorrow

In 2011, the first broadly downloaded smartphone app related to vision, EyeXam for iPhone, hit a million consumer downloads.18 This demonstrated high consumer demand for self-administered health measurements. There is now a plethora of other self-administered vision apps for visual acuity, color vision, visual skills, pupillometry, dark adaptation, retinal imaging and anterior eye imaging. All these apps can increase the public’s awareness of eye and vision issues while allowing eye doctors to access clinical data remotely. These apps do not even provide self-refraction to generate de novo eyeglass prescriptions.

It is hard to project if virtual reality headsets like Meta Quest 3 and Apple Vision Pro will become as common in everyday use as smartphones. If so, they could become the newly distributed platform to administer remote eye care.19,20 As an example, many of the new automated perimeters use headsets as the measurement platform, foreshadowing smartglasses and headsets to mediate more aspects of future remote eye care.21 Extended reality headsets are already delivering objective and subjective assessment measurements that include and extend beyond VA, including perimetry. Headsets also employ software for visual rehabilitation and vision therapy; for example, Luminopia (Luminopia) and Vivid Vision (Vivid Vision). Extended reality technology with machine learning software is forecast to assist practitioners in telehealth monitoring and patients in automated adjustment of settings to assist their visual rehabilitation and visual performance.22

Which Direction Shall Optometry Take?

The direction of the optometric profession will depend on our coordinated efforts. It takes decision-makers of our profession to coordinate direction—that would include representatives in the AOA and Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry along with state associations and local optometric societies—and the effort can also be through grassroots-level online groups like ODs on Facebook and ODWire. In the absence of coordination, online retail corporate entities may drive the market.

Eyeglass and contact lens prescription renewal by online companies is silently eroding patient visits to traditional optometric practices. To stem the loss of patients, more optometrists are extending patient prescriptions for corrective lenses, but this is a slippery slope. It may give consumers what they want, but not what they need. While prescription extension was common by optometrists during the COVID lockdown, its continued use by ODs may be more to reduce the loss of patients to online prescription renewal rather than doing what is best for their well-being.

Individual ODs may not have much influence on the overall trend of telehealth except in collective marketing efforts with colleagues and in optimizing their practice patterns. Meanwhile, the dominant third-party vision plan is exploring tele-optometry in response to some employers expressing interest in a remote care option.23 Under the supervision of eyecare professionals, remote technology can help provide improved access and convenience to patients. This would keep doctors making decisions for their patients rather than corporate executives.

It is an uphill climb to educate at large scale, getting the public to understand that VA and refraction are merely two components of a comprehensive exam and to understand the value of a comprehensive exam in disease detection and preventive care. Likewise, it is not simple to convey that a practitioner’s judgement is valuable to determine their eyeglass prescription, as the refraction is not always what is prescribed. Surely, online algorithms will continue to improve. Even so, there is no substitute presently for a clinician’s empathy nor their consultative skill to encourage the patient toward a favorable treatment path.

Consumer trendlines show the impetus for adoption of telehealth in eye care will continue.24 Among practitioners, the motivations and capabilities are more mixed. One JAMA Ophthalmology study found that telehealth in ophthalmology peaked during COVID and has returned to baseline.25 Because the specialized equipment of eyecare requires patients to physically go to an office, there may be a natural limit to how successful telehealth in eyecare can become. Nevertheless, even with these constraints in mind we still anticipate growth in tele-optometry. Just like how autorefraction and laser vision correction were once perceived as threats to the optometric profession, history suggests that optometrists will harness these new technologies to provide better and more efficient patient care.

Dr. Chou practices in San Diego at ReVision Optometry, a referral-based clinic for keratoconus and scleral lenses. He has consulted for two start-ups innovating in the field of refraction technology with remote capabilities.

Dr. Legerton is a Life Member of the American Optometric Association and is honored with the Outstanding Achievement Award; he is an Emeritus Fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and recipient of the Founders Award. He is an inventor on more than 200 US and international patent cases. His contributions to optometry span seven decades, including 26 years in private independent practice in San Diego.

1. Chou B. Opternative: one OD’s experience & advice. Rev Optom Business. reviewob.com/opternative-tell-patients. Published November 29, 2017. Accessed June 30, 2024. 2. Brault MW, Wittenborn JS, Rein DB. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system and American community survey estimates of vision difficulty prevalence. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024:e241993. 3. Zadnik K, Mutti DO, Adams AJ. The repeatability of measurement of the ocular components. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(7):2325-33. 4. Bullimore MA, Fusaro RE, Adams CW. The repeatability of automated and clinician refraction. Optom Vis Sci. 1998;75(8):617-22. 5. Gwiazda J, Weber C. Comparison of spherical equivalent refraction and astigmatism measured with three different models of autorefractors. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81(1)56-61. 6. Campbell CE, Benjamin WJ, Howland HC. Objective refraction: retinoscopy, autorefraction, and photorefraction. Borish’s clinical refraction. 2006:682-764. 7. Spivey B, Dreher AW. Portable diopter meter. uspto.report. uspto.report/patent/app/20140176909. Filed December 20, 2012. Accessed June 30, 2024. 8. Heiting G. Adjustable glasses: the future of multifocal lenses? All About Vision. www.allaboutvision.com/lenses/variable-focus.htm. Published February 27, 2019. Accessed June 30, 2024. 9. OTC hearing aids: what you should know. FDA. www.fda.gov/medical-devices/hearing-aids/otc-hearing-aids-what-you-should-know. Updated May 3, 2023. Accessed June 30, 2024. 10. Rakshit S, Wager E, Hughes-Cromwick P, Cox C, Amin K. How does medical inflation compare to inflation in the rest of the economy? Health System Tracker. www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/how-does-medical-inflation-compare-to-inflation-in-the-rest-of-the-economy. Published May 17, 2024. Accessed June 30, 2024. 11. Vankar P. U.S. national health expenditure as percent of GDP from 1960 to 2022. Statista. www.statista.com/statistics/184968/us-health-expenditure-as-percent-of-gdp-since-1960. Published February 16, 2024. Accessed July 4, 2024. 12. Topcon RDx remote comprehensive eye exam platform: perform refraction from anywhere with RDx. Topcon. topconhealthcare.com/products/rdx. Accessed July 5, 2024. 13. Zeiss Visu360—innovative platform for remote eyecare services: new opportunities for all eye care professionals. Zeiss. www.zeiss.com/vision-care/en/newsroom/news/2020/visu360-remote-eyecare-service.html. Published December 15, 2020. Accessed July 2, 2024. 14. Eyoto Group. A comparison of the diagnostic confidence and image quality between the Eyoto Theia (RDSL) and a predicate device. clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05783583. Nat Lib Med. Last updated April 7, 2023. Accessed July 5, 2024. 15. The new tele digital optical imaging system: welcome to Aetheia. Eyoto. eyoto.com/aetheia. Accessed July 5, 2024. 16. Our telehealth technology (2019). Stanton Optical. www.stantonoptical.com/blog/virtual-eye-care-with-telehealth-technology. Accessed June 30, 2024. 17. AOA calls for FDA investigation into retailer’s remote vision test. Am Optom Assoc. www.aoa.org/news/advocacy/federal-advocacy/aoa-calls-for-fda-investigation-into-retailers-remote-vision-test?sso=y. Published March 4, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2024. 18. EyeXam mobile vision screening app exceeds 1M downloads; sponsors added, new pro version debuts. Vision Monday. www.visionmonday.com/latest-news/article/eyexam-mobile-vision-screening-app-exceeds-1m-downloads-sponsors-added-new-pro-version-debuts-27490. Published March 30, 2011. Accessed June 30, 2024. 19. Mehta T. How AR glasses are going from niche gadget to smartphone replacement. Digital Trends Media Group. www.digitaltrends.com/mobile/ar-glasses-replace-smartphones-future-how. Published June 30, 2022. Accessed June 30, 2024. 20. Marr B. Will smart glasses replace smartphones in the metaverse? Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2022/09/07/will-smart-glasses-replace-smartphones-in-the-metaverse. Published September 7, 2022. Last updated September 8, 2022. Accessed June 30, 2024. 21. Leonard CY. A virtual reality check: where VR perimetry fits. Rev Ophthalmol. 2024;31(2):25-36. 22. Marsh J. Intelligent extended reality eyewear. uspto.report. uspto.report/patent/app/20230089522. Filed September 21, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2024. 23. Telemedicine. Vision Service Plan. www.vsp.com/faqs/appointments/telemedicine. Accessed June 30, 2024. 24. Massie J, Block SS, Morjaria P. The role of optometry in the delivery of eye care via telehealth: a systematic literature review. Telemed J E Health. 2022;28(12):1753-63. 25. Mosenia A, Li P, Seefeldt R, et al. Longitudinal use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic and utility of asynchronous testing for subspecialty-level ophthalmic care. JAMA Ophthalmol.2023;141(1):56–61. |