|

Q:

I have a one-month post-op cataract patient who told me on two successive visits that something was wrong with the vision in the right eye. The anterior segment was normal, and best-corrected acuity 20/25+1. What’s next?

A:

During the course of a busy day, it’s easy to ignore slightly reduced visual acuity. “Don’t,” emphasizes Dr. Ajamian, Director of Omni Eye Services of Atlanta. “Any time patients tell you there is a change in vision, investigate.” Refract carefully and document that you dilated the patient to come up with an answer. Doing so will protect yourself from legal consequences.

Dr. Ajamian has consulted on a number of cases over the years where doctors got into hot water by not taking vision loss seriously.

|

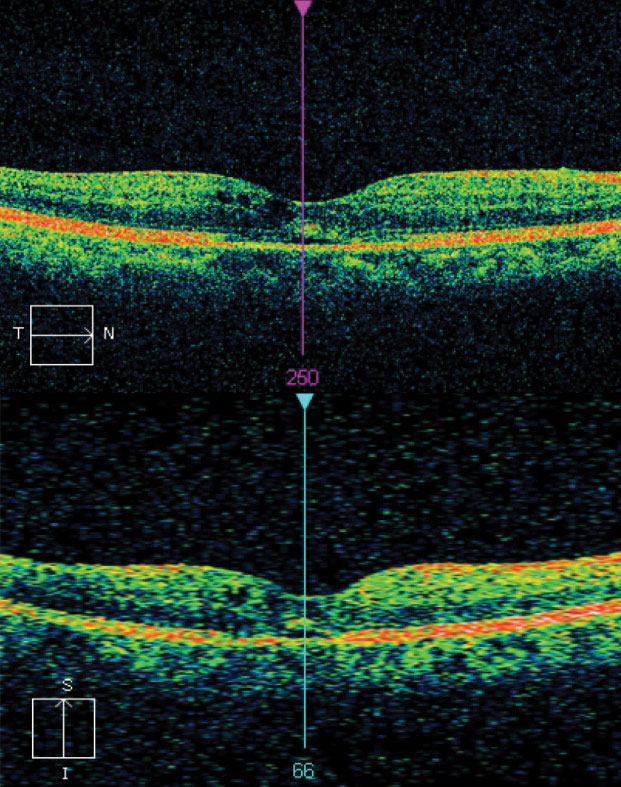

| Fig. 1.This macular OCT scan demonstrates increased average thickness OD, confirming a thorough search. |

Front to Back

Dr. Ajamian advises a methodical sweep of the eye from ocular surface to optic nerve. First, look at the cornea. With such small acuity loss to account for, the cause could be dry eye, map-dot-fingerprint dystrophy or other forms of ocular surface disease. Even if the slit lamp exam of the cornea appears normal, don’t forget to look at the topography.

Though you need to keep an open mind when investigating, stick with the most plausible scenarios first. Dr. Ajamian says he’s seen well-meaning clinicians order MRIs to try to explain reduced acuity, but something simpler and cheaper like topography would suffice. Especially in a post-surgical patient, you may encounter some induced astigmatism. “Even if topography is normal, consider the ‘hard lens trick’ that has rescued me many times,” adds Dr. Ajamian. Put a trial hard lens on the eye and over-refract; if the cornea was the issue, vision will return to 20/20.

Next, make sure both the anterior and the posterior chambers are clear. Carefully examine the crystalline lens—or, in the case of a pseudophake, the posterior capsule— using direct illumination, as well as retroillumination off the fundus. Milky nuclear sclerosis is the only cataract that can cause confusion because of the disparity between the clinician’s view in (clear) and the patient’s view out (reduced).

The fundus should be the next area of concern, and a dilated stereo exam using a 78D or 90D lens is the best way to rule out issues here. It affords you a more accurate look at elevation, cup-to-disc ratios and other essential elements of a fundus exam.

Optic nerve damage can also cause vision loss, so practitioners should not forget to look for cupping, pallor and nerve fiber layer loss such as wedge defects. Check optic nerve function by carefully ruling out an afferent pupillary defect and perhaps evaluate color vision. Visual fields and electrodiagnostic testing will be useful in many cases.

Every patient that cannot read the 20/20 line needs an explanation or a plan to explore the issue further. That plan may be as simple as having them follow up in a week or two to retake acuity. Not everyone is at their best every day, and subjective acuity is variable. “Keep in mind the visual axis, examine carefully all the structures in its path and you will be able to explain the unexplained in most cases,” says Dr. Ajamian. “If you can’t, document your concern and get specialty help when needed.”

Unmasking the Culprit

“Our patient insisted that something wasn’t right, and we dilated and saw what appeared to be early cystoid macular edema,” says Dr. Ajamian. A macular optical coherence topography scan confirmed this, and the patient was started on a topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug BID and prednisolone acetate 1% QID for at least six weeks (Figure 1). Any delay in treatment could have spelled disaster.”