|

Managing Pediatric Ocular Pathology

Safe treatment of these patients requires a comprehensive understanding of available therapeutics.

By Amy Waters, OD

Release Date: March 15, 2022

Expiration Date: March 15, 2025

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: 2 hours

Jointly provided by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and Review Education Group

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Appraise how to treat pediatric ocular pathologies.

- Identify which drugs are approved for what ages.

- Select the right medication and dosage for various conditions.

- Describe strategies to minimize adverse effects when treating pediatric patients.

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in managing pediatric patients.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by PIM and the Review Education Group. PIM is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education and the American Nurses Credentialing Center to provide CE for the healthcare team. PIM is accredited by COPE to provide CE to optometrists.

Reviewed by: Salus University, Elkins Park, PA

Faculty/Editorial Board: Amy Waters, OD

Credit Statement: This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. Activity #123535 and course ID 77443-PH. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statements: PIM requires faculty, planners and others in control of educational content to disclose all their financial relationships with ineligible companies. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted and mitigated according to PIM policy. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high-quality, accredited CE activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in healthcare and not a specific proprietary business interest of an ineligible company.

Those involved reported the following relevant financial relationships with ineligible entities related to the educational content of this CE activity: Author: Dr. Waters is part of PEDIG and has been involved in multiple research studies. Managers and Editorial Staff: The PIM planners and managers have nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group planners, managers and editorial staff have nothing to disclose.

|

| Corneal and conjunctival abrasion with subconjunctival hemorrhage. A Burton/Woods lamp is beneficial for visualization in infants and toddlers. Click image to enlarge. |

Children often present unique yet rewarding challenges when it comes to prescribing medications for ocular pathology. Drugs that are used in adults may sometimes be contraindicated in children or not approved for use at all in this patient population. The dosage of oral medications is also very different in children compared with adults. While many classes of ophthalmic medications have information for pediatric use, it is estimated that over 80% of all medications that have been approved in adults do not have information for pediatric use.

The research on drug safety in children has seen improvements over time. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) of 2007 allows for six months of marketing exclusivity if children are included in the research for the new drug. The Pediatric Research Equity Act can require pediatric research into new drugs under certain circumstances.1

When ocular pathology strikes, what drugs and dosages can we use for the pediatric patient population? This article will review common anterior segment conditions, as well as the topical and oral medications used to treat them in children. It will provide the necessary tools to safely manage pediatric ocular pathology using available therapeutic interventions.

Conjunctivitis

Both bacterial and viral conjunctivitis are relatively common in pediatric patients; therefore, optometrists should remain aware of how to best manage these conditions.

Bacterial conjunctivitis. This condition is usually self-limiting, but treatment can decrease its course, prevent the spread of infection and cause children to be able to return to school more quickly. For these reasons, bacterial conjunctivitis in children is most often treated with topical antibiotics. Cultures are typically not obtained and are usually not necessary. However, suspected neonatal conjunctivitis is an emergency and requires cultures and potential hospitalization. Most eye drops require a five- to seven-day course and are dosed three to four times daily. Many antibiotic ophthalmic drops include prescribing information for children. The majority are dosed the same as in adult patients.

A recent study on bacterial conjunctivitis found that one in four cases were polybacterial. A broad-spectrum antibiotic is warranted in pediatric bacterial conjunctivitis.2,3 Moxifloxacin hydrochloride (Moxeza, Alcon/Novartis; Vigamox, Alcon and A-S Medication Solutions) has been approved for all age ranges and is typically well tolerated. The dosage is one drop three times daily for seven days.4 Trimethoprim/polymyxin B sulfate is also approved in children over two months of age but needs to be administered more frequently. The recommended dosage is one drop every three hours, not to exceed six drops per day for seven to 10 days.5 The most common cause for bacterial conjunctivitis in young children is Haemophilus influenza, which has also been noted to cause otitis media. In a child with a concurrent ear infection and red eye, bacterial conjunctivitis should be considered.6

|

| Patient with active BKC, peripheral corneal infiltrates and capped meibomian glands. Click image to enlarge. |

Viral conjunctivitis. The hallmark sign of this condition is a follicular response on the conjunctiva with a red, watery eye. There is currently no well tolerated treatment for viral conjunctivitis in young pediatric patients, as they are not very tolerant to povidone-iodine treatments that have been described to treat adult viral conjunctivitis off-label. Supportive therapy such as cold compresses and artificial tears are the primary treatment. If there is significant discomfort for the child, consider a treatment with an antibiotic/steroid combination or a topical steroid. If there are significant corneal infiltrates, treat this with a topical steroid; however, this therapy option should be reserved for more severe cases. If topical steroids are pursued, a softer steroid such as loteprednol etabonate (Alrex, Bausch + Lomb; Lotemax, Bausch + Lomb; Eysuvis, Kala Pharmaceuticals) or fluorometholone is preferred since there is not a need for deep penetration into the eye and because these medications are less likely to cause elevation of IOP.7

Since the signs and symptoms of different types of conjunctivitis can overlap in cases of acute red eye, an in-office rapid test can evaluate whether the infection is adenovirus. This does not rule out all causes of viral conjunctivitis but can be especially helpful in deciding on treatment if there is a positive result.8

Pediatric Trauma

Children commonly present with ocular trauma. Those with closed globe injuries typically respond quite well to treatment. One difficulty that arises with pediatric trauma is that injuries are sometimes not witnessed by adults and history may be limited. The clinician may also not get a complete history because the patient is more hesitant to offer details. In all cases of blunt or unwitnessed trauma, a complete dilated eye exam is indicated.

A pediatric corneal abrasion is treated slightly different in this young population than in adults. In young children, bandage contact lenses are not as easily placed or removed. A Cochrane review did not find sufficient evidence of benefit with this therapy and recommended more research into the topic.9 If a pediatric patient is unable to keep their hands away from their eyes and the abrasion is worsening—or not improving—a pressure patch can be considered. However, the patient should be managed closely due to the increased risk of microbial infection. Bandage contact lenses should be considered if a patient is old enough to tolerate insertion and removal.

|

| This case of active BKC and corneal infiltrates is best treated with combined topical antibiotics and steroids. Click image to enlarge. |

Topical antibiotics include moxifloxacin hydrochloride drops, erythromycin ointment, trimethoprim/polymyxin B sulfate drops and ciprofloxacin hydrochloride ointment. Ointment tends to provide better relief after corneal abrasions and is sometimes easier to instill in children after injuries. Ointment is typically prescribed to be used three to four times daily. Educate caregivers that these treatments should be used prior to naptime and bedtime.

Hyphema, which is also more common in children, can occur with blunt trauma and commonly happens because of sports injuries.10 Due to the lack of availability of homatropine, first-line treatments include cyclopentolate 1% twice daily or atropine 1% once daily with a topical steroid. Prednisolone acetate (Pred Forte, Allergan; Pred Mild, Allergan) should be dosed QID. Once the hyphema is resolved, the cycloplegic agent is discontinued and the steroid drop is tapered.

Patients need to be followed very closely the first 48 hours and closely until the hyphema resolves, especially in cases of elevated IOP. Encourage bedrest, with a head elevation of 45° and no NSAIDS, as this can increase the risk of rebleed. Patients and parents should be educated on the short- and long-term risk of glaucoma after hyphema. Risk of rebleed is highest in the first two to five days after injury. The patient should also be thoroughly evaluated for other ocular injuries.10

Sickle cell disease with hyphema carries a much greater risk of increased IOP and secondary complications due to the sickling of red blood cells in the trabecular meshwork. Inquire about a history of African or Middle Eastern decent. If sickle cell status is unknown in an at-risk population, screen the patient for sickle cell disease. Atropine is typically contraindicated in patients with a heart disorder, so it is important to obtain medical history including any cardiac problems. Discussions with the patient’s cardiologist or primary care physician may be indicated to weigh risks and benefits of treatment in those with a positive cardiac history.

If IOP rises during the treatment of hyphema, there are multiple medications to consider. Dorzolamide hydrochloride/timolol maleate is a good first-line medication combination if the patient does not have a history of asthma or other contraindications. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists have been shown to have significant side effects, including respiratory suppression in children, so they are not recommended in young patients. Many practitioners do not prescribe them in patients younger than 12 years of age.10-15 Prostaglandin analogs are typically not first-line for treatment of ocular hypertension associated with hyphema because of the possibility that they may increase intraocular inflammation.

|

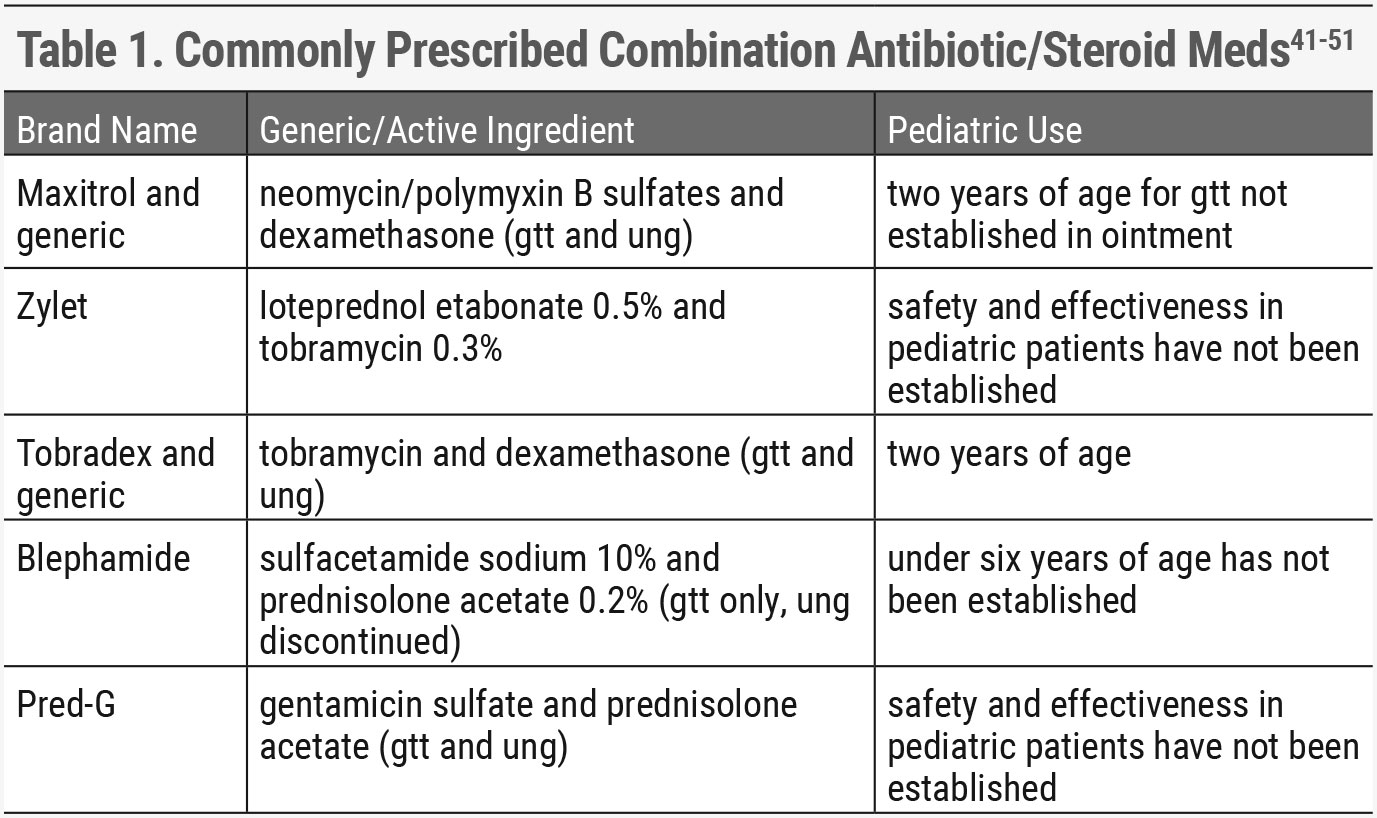

| Click table to enlarge. |

Periorbital and Orbital Cellulitis

Both of these conditions are also more common in children compared with adults.16 Typical causes of periorbital and orbital cellulitis include chalazion/hordeolum, trauma and sinusitis. Orbital cellulitis is a more severe condition and requires imaging, hospitalization and IV antibiotics. If an abscess is present, the patient may require surgical drainage for treatment. Orbital cellulitis has a high association with sinusitis.

Both conditions present with a red, painful, swollen eyelid. In periorbital cellulitis, vision is not affected, other ocular structures are normal and ocular motilities remain intact. Orbital cellulitis signs can include afferent pupillary defect, extraocular motility restrictions, decreased vision and retinal and optic nerve findings as well as anterior chamber reaction. Any of these signs indicate an emergency hospitalization and further evaluation. Fever is not a good differentiator between orbital and periorbital cellulitis.

In cases of periorbital cellulitis, children under two years old—or someone unable to be compliant with oral medications—may require hospitalization. If a patient is on oral medications and still worsening, additional work-up is indicated. Typical follow-up after initiation of oral medications is two days. Strict return instructions with signs of worsening infection and orbital cellulitis should be given to the family. Worsening is an indication for potential hospital admission or emergency room services.17

Oral antibiotics to consider as first-line treatments include amoxicillin/clavulanate, cephalexin and clindamycin.17-19 When dealing with a high prevalence of MRSA or an at-risk population, clindamycin should be considered as initial treatment. Worsening while on antibiotics or no improvement at 48 hours is a sign of inadequate treatment. Some sources advocate for clindamycin as a primary treatment instead of amoxicillin/clavulanate or cephalosporins due to increased incidence of MRSA.20,21 Children over 40kg are typically given an adult dosage. Amoxicillin/clavulanate, cephalexin and clindamycin are available in oral suspensions. Consider probiotics or yogurt to prevent gastrointestinal upset while on oral antibiotics. In children under five years old and when prescribing clindamycin, consider consulting the patient’s pediatrician.17

|

| Limbal infiltrates and injection in a patient with active BKC. Click image to enlarge. |

Pediatric Lid Disease

This is another common issue among children. Blepharitis and chalazion can typically be conservatively managed with lid hygiene and warm compresses. If they do not resolve, referral for surgical removal may be suggested. Tetracyclines are contraindicated in younger children due to teeth discoloration and should not be used.

Occasionally after chalazion or trauma, a pyogenic granuloma can develop. These typically improve with a short course of topical steroids dosed two to three times daily. If large pyogenic granulomas do not improve with topical treatment, some surgeons will remove them. Others prefer to monitor because they typically do resolve over time.

Cases of blepharokeratoconjunctivitis (BKC) can cause irregular astigmatism, corneal scarring and be an amblyogenic factor in children. In its active phase, it is most often managed with topical steroids and antibiotics to reduce inflammation and bacterial load, as well as lid hygiene and warm compresses. Most treatments of BKC are off-label.

Hordeolum can also typically be treated in combination with lid hygiene and a topical antibiotic or topical antibiotic/steroid combination. An ointment is preferred. If topical medications are not improving the hordeolum and periorbital cellulitis is suspected, then an oral antibiotic should be considered.

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Infections

Primary HSV-1 infections occur most commonly on the lips, but children can present with HSV dermatitis of the eyelids and HSV keratitis. Both topical ganciclovir and oral acyclovir have been studied and found to work well for treatment of herpes simplex keratitis.22 Oral acyclovir is less expensive and is more readily covered by insurance, so it is a first-line choice for both pediatric herpes simplex keratitis and herpes simplex dermatitis of the eyelids. This is off-label use. Topical ganciclovir initial dosage is five times a day which could cause less compliance than oral medications. Topical ganciclovir has not been studied in children under two years old.23 Avaclyr (acyclovir ophthalmic ointment 3%, Fera) was FDA-approved in 2019, but it is not commercially available, and its anticipated availability is currently unknown.

|

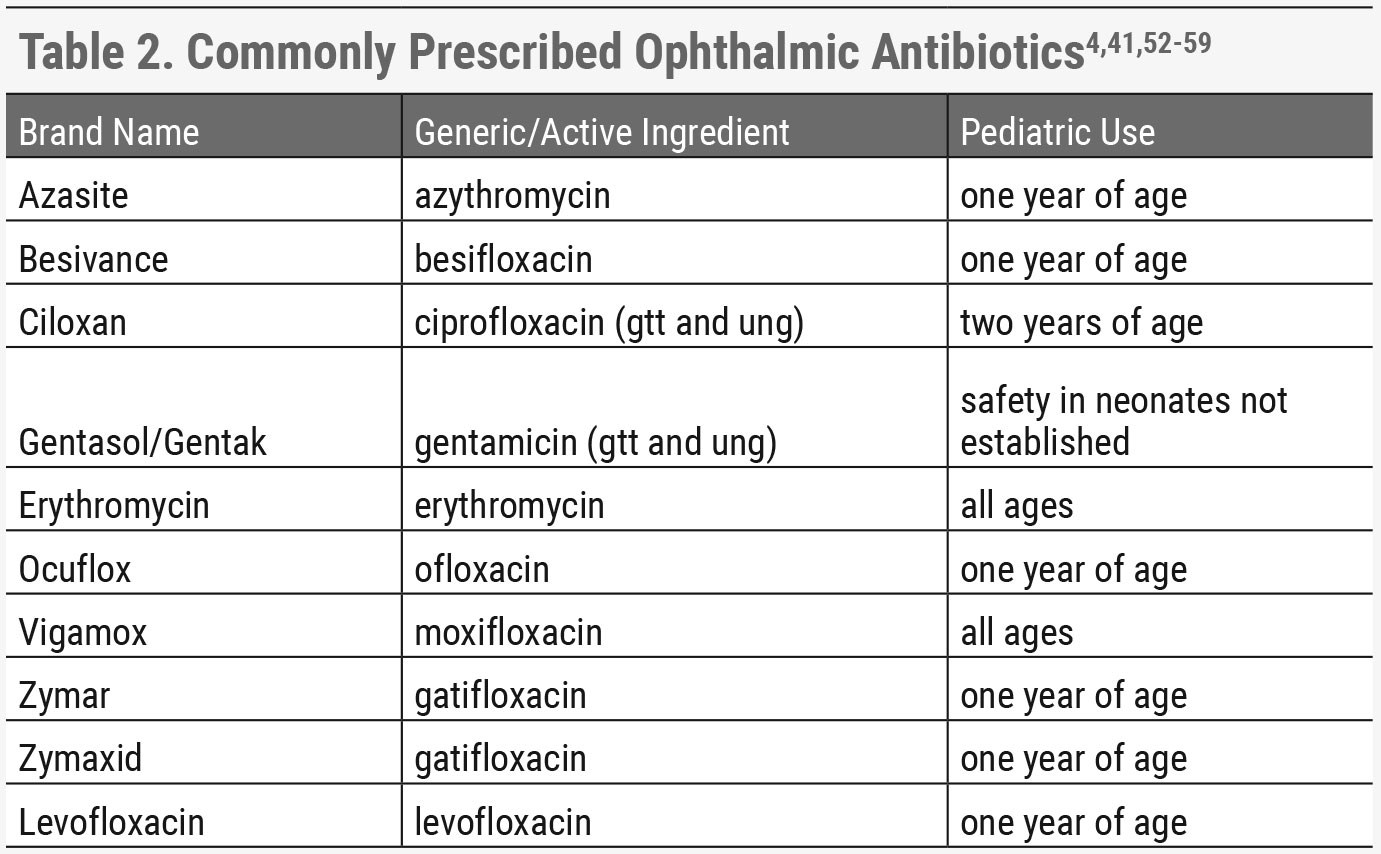

| Click table to enlarge. |

Recommended dosage of oral acyclovir in pediatrics changes frequently, so it is recommended to consult a prescriber’s digital reference or the patient’s pediatrician when prescribing oral antiviral medications in children. Because initial outbreaks of HSV infections are more likely to present with symptomatic infections, pediatricians frequently prescribe oral antiviral medications and are an excellent resource for dose recommendations. With oral valacyclovir, there is an increased cost, so more pediatric studies have looked at oral acyclovir for herpes simplex keratitis than valacyclovir. It can be dosed with less frequency, which is beneficial in pediatric patients.

If the patient is having recurrent keratitis or dermatitis suppression, therapy may be indicated. A pediatrician or infectious disease expert should be consulted due to the increased risk of side effects with chronic suppression in children with oral antivirals due to renal effects.

Given HSV keratitis can be visually devastating in childhood, close follow-up and treatment is required. A higher percentage of children than adults may present with bilateral disease. Children in an amblyogenic age range may develop amblyopia as this is often a unilateral or asymmetric disease. This can be caused by transient opacification of the cornea during a critical period, corneal scarring or irregular astigmatism. In cases of irregular astigmatism, unilateral fitting of a rigid gas permeable or scleral lens may be required to optimize vision and treat amblyopia.24-27

Any time visual acuity is decreased in a child with a history of HSV keratitis, a trial period of amblyopia treatment is indicated. If best-corrected visual acuity after treatment is 20/40 or worse, the parents should be educated on the importance of polycarbonate glasses for safety, especially if the child plays sports. Referral to a corneal specialist is warranted in recurrent disease and central corneal ulcers. Neonatal HSV and eczema herpeticum require emergent care. Eczema herpeticum is a disseminated rash occurring with HSV, associated with atopy and almost exclusively occurs in children.24-27

|

| Hordeolum that would benefit from a topical antibiotic/steroid combination ointment as first-line treatment. Click image to enlarge. |

Allergic Conjunctivitis, Vernal (VKC) and Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis (AKC)

Allergies with ocular symptoms are another key pathology that can require optometric intervention.

Allergic conjunctivitis. Allergies are commonly present in childhood, and a high percentage of these children will have ocular symptoms. Allergic conjunctivitis can present seasonally or be year-round. The mainstay treatment is ophthalmic antihistamine and allergen avoidance. Cold compresses and artificial tears can also be used for comfort and to rinse the ocular surface of allergens.28 Once daily antihistamine drops can be beneficial in children because they are easy to use and can increase compliance. If symptoms are not improving, a short course of topical steroids can be considered.29

VKC. This is a more serious form of ocular allergies in children that typically presents around eight years of age. It occurs more commonly in males and has a seasonal component, where it is usually worse in the spring and summer and improves in the winter. Hallmark signs are Horner Trantas dots, giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) or a combination of the two. Always look underneath the upper eyelid in suspected cases because sometimes GPC may be the only presenting sign. Horner Trantas dots also present more commonly in the upper limbal area of the cornea.

These patients are usually highly symptomatic, and topical antihistamines alone will not treat active disease. Topical steroids in conjunction with topical antihistamines are a first-line treatment with a goal of tapering off the topical steroid as symptoms improve.30 If the patient’s symptoms increase on tapering of topical steroids, or if they develop steroid-induced hypertension, topical cyclosporine or compounded tacrolimus can be considered.

There have been multiple studies showing the benefits of off-label use of topical immunomodulators such as topical cyclosporine or compounded tacrolimus for controlling inflammation and reducing recurrence of symptoms with VKC. Cyclosporine (Restasis, Allergan; Cequa, Sun Pharmaceuticals) at twice daily dosing in combination with a topical antihistamine is a good first option.30 A generic version of cyclosporine will soon be available. Verkazia (Santen) is a new formulation of cyclosporine that was recently FDA-approved for treatment of VKC and will likely be available in the spring of 2022. It represents the first immunomodulator to be approved for treatment of VKC. Its safety and effectiveness have been studied in children four to 18 years of age. The recommended dosage is four times daily. Compounded tacrolimus 0.1% has also shown good efficacy in the treatment of VKC.31-33

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

AKC. This condition has findings very similar to VKC except that it does not have seasonal variation; AKC patients have signs and symptoms all year long. They also tend to have a history of atopy and symptoms presenting at an older age range, typically as teenagers. These patients are more likely to need immunomodulators to control disease and can have significant corneal changes that can affect vision. A corneal specialist referral may be indicated. All patients with AKC or VKC should be referred to an allergist if they have not already established care.

Topical Ophthalmic Medications

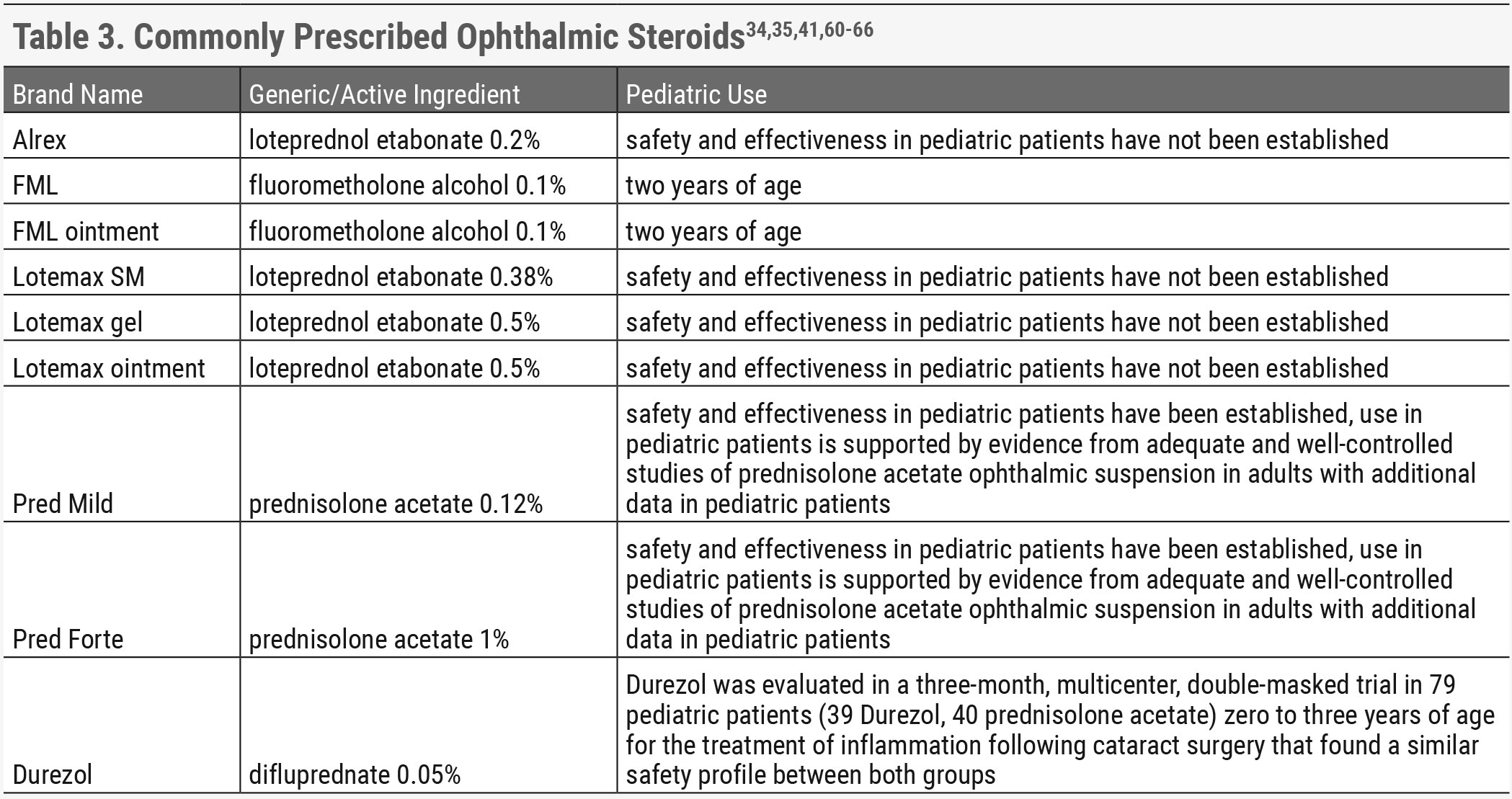

There are very few topical medications that are contraindicated in children, but not all have received approval for use in all ages of children. Most topical antibiotics and antihistamines have labeling for pediatric use. Most topical steroids do not have information in their labeling for pediatric use. Fluorometholone is approved for children two years and older.34,35 The dosage of topical ophthalmic medications in children is typically the same as the adult dosage.

Exercise caution when keeping medications away from children, especially eye drops that usually do not have any type of child safety mechanism. In 2012, the FDA released information regarding over-the-counter eye drops and nasal sprays with accidental ingestion in children. It is important to discuss drug safety with the family as a general course of practice. It is best to avoid any drugs containing tetrahydrozoline, naphazoline or oxymetazoline because there are other, more effective medications that can treat the same conditions.36

Since most ocular lubricants are not prescription-based, the FDA has not evaluated their use or safety in adults or children. These medications are commonly used in pediatric practice and generally considered safe for children.

|

| A pyogenic granuloma that occurred post-chalazion. First-line treatment is topical steroids. They are often hidden under the lid, and Chi will evert when the lid is pulled down. Click image to enlarge. |

Oral Medications

As a child grows, there are changes in absorption, metabolism, distribution and excretion of medications. This is one of the reasons why medications are based on weight, sometimes in conjunction with the age of the child. Typically, there is a maximum dose that is recommended, and the dose given should never exceed the adult dosage of the medication that is being prescribed. When treating children younger than five years old, it may be beneficial to contact the child’s pediatrician when dosing medications.

The dosage recommendation for oral medications in children is based on mg/kg. The drug recommendations may be written as mg/kg/dose or mg/kg/day. It is important to differentiate this when referencing dosage recommendations. Dosage recommendations in children tend to change more frequently than adults, so it is important to always reference dosage recommendations prior to prescribing. Often if children are over 40kg and 12 years or older, the recommendation is the adult dosage, but it is important to always check as every medication is different.

Common Oral Antibiotics

There are several oral antibiotics ODs should be aware of when managing pediatric ocular pathology.

Augmentin. This is an excellent antibiotic for soft tissue infections, but the dosing can be somewhat challenging, and it does not provide MRSA coverage. It comes in multiple dose forms, and some are approved for only certain age or weight ranges. Some dose forms are divided into twice daily dosing, some into three times a day dosing. If the incorrect dose form is used, it can result in either too much or not enough clavulanate, which could cause undertreatment of the infection or significant gastrointestinal upset.17

Dosage is based on the amount of amoxicillin. Most recommended formulation for children with soft tissue infections is the 7:1 dose form. One commonly used 7:1 dose form of oral suspension is amoxicillin 400mg/clavulanate 57mg per 5ml. The most common recommended dosage is between 25mg/kg/day and 45mg/kg/day in divided twice daily dosage form, not to exceed 1,750mg of amoxicillin a day.33 For children with periorbital cellulitis, pursuing the higher end of the dose range may help reduce the risk of undertreating the infection. Some sites suggest not prescribing ES-600 suspension in patients 40kg and over due to lack of data on ES-600 suspension in this patient category.37

Keflex. This medication is also a treatment option for periorbital cellulitis. The recommended dosage for Keflex is 25mg/kg/day to 100mg/kg/day divided into doses every six to eight hours, not to exceed 2,000mg/kg/day. For children over 40kg and adults, the recommended dosage is one gram twice a day.38 It does not provide MRSA coverage.

Clindamycin. This treatment can be considered as a first-line or when MRSA is suspected. It is contraindicated in infants and has more side effects than Augmentin and Keflex. Consult a pediatrician for dosage due to the increased risk of side effects. It has been associated with severe colitis.

Bactrim. There is a higher rate of allergies with Bactrim due to sulfa-containing medication, but it can be considered in suspected MRSA infections. Consult a pediatrician prior to prescribing due to the increased risk of side effects. It should not be used as a monotherapy due to poor coverage of Streptococcus.20

Antiviral Medications

Topical ganciclovir is approved for treatment of HSV keratitis in children aged two and older. Oral acyclovir has been studied and works well as an off-label treatment for HSV keratitis in children.22,23 Oral acyclovir is less expensive and is more readily covered by insurance, so it is our first-line choice for both herpes simplex keratitis and herpes simplex dermatitis of the eyelids. Recommended dosage of oral acyclovir in pediatrics changes frequently, therefore I would always recommend consulting a prescriber’s digital reference or the patient’s pediatrician when prescribing acyclovir.

Contraindicated Medications

Just as an optometrist must know which drug options to choose, it is equally important to recognize when a medication is contraindicated for a patient.

Alpha agonists. These medications are typically contraindicated in children younger than eight to 12 years old due to the significant side effect profile. This would also be a contraindication for the use of apraclonidine in suspected Horner’s syndrome in young children. Brimonidine and apraclonidine HCI are not recommended for use due to central nervous system effects and respiratory suppression in young children.11-15

Apraclonidine may have a safer side effect profile than brimonidine, but there have been case reports of central nervous system effects in young infants on apraclonidine, especially those who are younger than six months of age.39 No approved antidote is currently available for use in alpha-2 agonist toxicity, but some poison control centers may recommend naloxone. If a patient had known exposure to these medications and is exhibiting extreme drowsiness, inability to rouse or other signs of respiratory suppression, they should go to the emergency department immediately.11-15

Tetracyclines. This treatment is relatively contraindicated in children younger than eight years old due to the risk of tooth discoloration. The minimum age used to be 12 years old but has been decreased to eight years old due to completion of tooth calcification by this age. In most ophthalmic infections, there are other medications with a better safety profile in children.40

Takeaways

In summary, there are many anterior segment conditions that present uniquely or more commonly in children that can be treated with topical and oral medications. Most topical ophthalmic medications are dosed the same as adult dosages. If children require oral medications, they should always be dosed by weight in mg/kg. It is often beneficial to consult a prescriber’s digital reference or the patient’s pediatrician because dosage of medications in children change more often than adults.

More medications are being researched in pediatrics, and most topical ophthalmic medications have been approved for use in children. It is always important to make sure that there are no significant contraindications prior to prescribing for children. A comprehensive understanding of the available options and how to use them is key when caring for this patient population.

Dr. Waters is an optometrist at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City and an assistant professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. She works exclusively with pediatric patients, with an emphasis on amblyopia, strabismus and ocular disease. She is part of PEDIG and has been involved in multiple research studies.

1. US Food & Drug Administration. Office of New Drugs Unit List: Pediatric Regulations. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cderworld/index.cfm?action=newdrugs:main&unit=4&lesson=1&topic=8. Accessed February 25, 2022. 2. Blondeau JM, Proskin HM, Sanfilippo CM, et al. Characterization of polybacterial versus monobacterial conjunctivitis infections in pediatric subjects across multiple studies and microbiological outcomes with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:4419-30. 3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Bacterial conjunctivitis. eyewiki.aao.org/conjunctivitis#bacterial_conjunctivitis. Accessed February 25, 2022. 4. US Food & Drug Administration. Vigamox. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2003/21598_vigamox_lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 5. Prescriber’s Digital Reference. Polymyxin B sulfate/trimethoprim - drug summary. www.pdr.net/drug-summary/polytrim-polymyxin-B-sulfate-trimethoprim-1108. Accessed February 25, 2022. 6. Hu YL, Lee PI, Hsueh PR, et al. Predominant role of Haemophilus influenzae in the association of conjunctivitis, acute otitis media and acute bacterial paranasal sinusitis in children. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11. 7. Pleyer U, Ursell PG, Rama P. Intraocular pressure effects of common topical steroids for post-cataract inflammation: are they all the same? Ophthalmol Ther. 2013;2(2):55-72. 8. Holtz KK, Townsend KR, Furst JW, et al. An assessment of the AdenoPlus point-of-care test for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis and its effect on antibiotic stewardship. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1(2):170-5. 9. Lim CH, Turner A, Lim BX. Patching for corneal abrasion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(7):CD004764. 10. Gragg J, Blair K, Baker MB. Hyphema. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. 11. Cimolai N. A review of neuropsychiatric adverse events from topical ophthalmic brimonidine. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2020;39(10):1279-90. 12. Ghaffari Z, Zakariaei Z, Ghazaeian M, et al. Adverse effects of brimonidine eye drop in children: a case series. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46(5):1469-72. 13. Gill K, Bayart C, Desai R, et al. Brimonidine toxicity secondary to topical use for an ulcerated hemangioma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(4):e232-4. 14. Kiryazov K, Stefova M, Iotova V. Can ophthalmic drops cause central nervous system depression and cardiogenic shock in infants? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(11):1207-9. 15. Eldib AA, Patil P, Nischal KK, et al. Safety of apraclonidine eye drops in diagnosis of Horner syndrome in an outpatient pediatric ophthalmology clinic. J AAPOS. 2021;25(6):336. 16. National Library of Medicine. Periorbital cellulitis. medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000976.htm. Accessed February 25, 2022. 17. MSF medical guidelines. Periorbital and orbital cellulitis. medicalguidelines.msf.org/viewport/cg/english/periorbital-and-orbital-cellulitis-16689736.html. Accessed February 25, 2022. 18. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Clinical pathway for patient with suspected preseptal or orbital cellulitis. www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/preseptal-or-orbital-cellulitis-clinical-pathway. Accessed February 25, 2022. 19. Garrity J. Preseptal and orbital cellulitis (periorbital cellulitis). Merck Manuals. 2021. www.merckmanuals.com/professional/eye-disorders/orbital-diseases/preseptal-and-orbital-cellulitis#:~:text=(periorbital%20Cellulitis)&text=Symptoms%20include%20eyelid%20pain%2C%20discoloration,antibiotics%20and%20sometimes%20surgical%20drainage. Accessed February 25, 2022. 20. Ventocilla M. Periorbital cellulitis (preseptal cellulitis) empiric therapy. Medscape. 2021. emedicine.medscape.com/article/2017741-overview. Accessed February 25, 2022. 21. Bae C, Bourget D. Periorbital cellulitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. 22. Vadoothker S, Andrews L, Jeng B, et al. Management of herpes simplex virus keratitis in the pediatric population. Pediat Infect Dis J. 2018;37(9):949-51. 23. Rx List. Zirgan. www.rxlist.com/zirgan-drug.htm#clinpharm. Accessed February 25, 2022. 24. Serna-Ojeda JC, Ramirez-Miranda A, Navas A, et al. Herpes simplex virus disease of the anterior segment in children. Cornea. 2015;34 Suppl 10:S68-71. 25. Liu S, Pavan-Langston D, Colby KA. Pediatric herpes simplex of the anterior segment: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(10):2003-8. 26. Luccarelli SV, Lucentini S, Martellucci CA, et al. Impact of adherence (compliance) to oral acyclovir prophylaxis in the recurrence of herpetic keratitis: long-term results from a pediatric cohort. Cornea. 2021;40(9):1126-31. 27. Schwartz GS, Holland EJ. Oral acyclovir for the management of herpes simplex virus keratitis in children. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(2):278-82. 28. Ventocilla M. Allergic conjunctivitis treatment & management. Medscape. 2019. emedicine.medscape.com/article/1191467-treatment. Accessed February 25, 2022. 29. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Allergic conjunctivitis. aapos.org/glossary/allergic-conjunctivitis. Accessed February 25, 2022. 30. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. eyewiki.aao.org/vernal_keratoconjunctivitis#treatment. Accessed February 25, 2022. 31. Biermann J, Bosche F, Eter N, et al. Treating severe pediatric keratoconjunctivitis with topical cyclosporine A. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. November 3, 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. 32. Caputo R, Marziali E, de Libero C, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of tacrolimus 0.1% in severe pediatric vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2021;40(11):1395-401. 33. Roumeau I, Coutu A, Navel V, et al. Efficacy of medical treatments for vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(3):822-34. 34. US Food & Drug Administration. FML. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=016851. Accessed February 25, 2022. 35. US Food & Drug Administration. FML (ointment). www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=017760. Accessed February 25, 2022. 36. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: serious adverse events from accidental ingestion by children of over-the-counter eye drops and nasal sprays. 2012. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-serious-adverse-events-accidental-ingestion-children-over-counter-eye. Accessed February 25, 2022. 37. US Food & Drug Administration. Augmentin ES-600. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/050755s014lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 38. US Food & Drug Administration. Keflex. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/050406s013lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 39. Stayer K, Kane A. Topical apraclonidine toxicity in a 4-month-old infant. Toxicol Commun. 2018;2(1):105-6. 40. C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital University of Michigan Health. Tetracycline. www.mottchildren.org/health-library/d00041a1. Accessed February 25, 2022. 41. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA-Approved Drugs. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm. Accessed February 25, 2022. 42. US Food & Drug Administration. Maxitrol (neomycin and polymyxin B sulfates and dexamethasone ophthalmic ointment). www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/050065s065lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 43. US Food & Drug Administration. Maxitrol (neomycin and polymyxin B sulfates and dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension). www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/050023s037lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 44. US Food & Drug Administration. Zylet. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/050804lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 45. US Food & Drug Administration. Tobradex (tobramycin and dexamethasone ophthalmic ointment). www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/050616s040s041lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 46. US Food & Drug Administration. Tobradex (tobramycin and dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension). www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/050592s044s046lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 47. US Food & Drug Administration. Neomycin and polymyxin B sulfates and dexamethasone (ANDA 062938). www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=064063. Accessed February 25, 2022. 48. US Food & Drug Administration. Neomycin and polymyxin B sulfates and dexamethasone (ANDA 064063). www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=064063. Accessed February 25, 2022. 49. US Food & Drug Administration. Blephamide (suspension; ophthalmic). www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=012813. Accessed February 25, 2022. 50. US Food & Drug Administration. Blephamide (ointment). www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=087748. Accessed February 25, 2022. 51. US Food & Drug Administration. Current and resolved drug shortages and discontinuations reported to FDA. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/dsp_activeingredientdetails.cfm?ai=sulfacetamide+sodium+and+prednisolone+acetate+ophthalmic+ointment&st=d&tab=tabs-3&i=15&panel=15. Accessed February 25, 2022. 52. US Food & Drug Administration. Azasite. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/050810lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 53. US Food & Drug Administration. Besivance. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022308lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 54. US Food & Drug Administration. Ciloxan. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/019992s026lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 55. Medscape. Erythromycin ophthalmic (Rx). reference.medscape.com/drug/ilotycin-ophthalmic-erythromycin-ophthalmic-343573. Accessed February 25, 2022. 56. US Food & Drug Administration. Ocuflox. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019921s021lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 57. US Food & Drug Administration. Zymar. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2003/21493_zymar_lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 58. US Food & Drug Administration. Zymaxid. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022548s000lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 59. US Food & Drug Administration. Quixin. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2000/21199lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 60. US Food & Drug Administration. Alrex. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/1998/20803lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 61. US Food & Drug Administration. Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel). www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202872lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 62. US Food & Drug Administration. Lotemax (drops). www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=020583. Accessed February 25, 2022. 63. US Food & Drug Administration. Lotemax (ointment). www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&applno=200738. Accessed February 25, 2022. 64. US Food & Drug Administration. Pred Mild. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/017100s045lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 65. US Food & Drug Administration. Pred Forte. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/017011s050lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. 66. US Food & Drug Administration. Durezol. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/022212lbl.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022. |