Recently, during dinner with two colleagues, the topic of the billing dilemma surrounding dry eye arose. I found the conversation both intriguing and bewildering, as I didn’t see the dilemma in quite the same way that they did.

Dry eye, depending on how it is classified, could be considered at epidemic levels within the United States. Well over half of the patients that an OD sees on any given day have some component of ocular surface disease. It may manifest itself differently with every patient: the contact lens patient who isn’t getting her full day of wear, the computer programmer with fluctuating vision that gets better when he blinks, the fifty-something patient who’s eyes are always red and irritated, etc. So what’s the dilemma? How the practitioner defines the services related to dry eye and who is financially responsible for them.

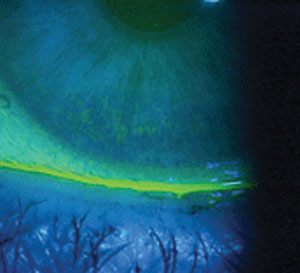

| |

| Corneal staining revealing dry eye. |

While I understand there are exceptions to every rule, the constructs for defining and delineating our services are fairly straightforward. I’m not talking about the clinical side of things, but more from the perspective of how the patient presents to the office. Let’s discuss two common scenarios:

Scenario One

A patient schedules an eye examination and has a managed vision care plan that covers their “annual eye examination and refraction.” During the course of the examination, you discover she has some clinical signs of dry eye. She also has medical coverage for which you are a participating provider.

Because she didn’t present with “complaints or symptoms of an eye disease or injury,” her medical insurance benefits won’t get involved with respect to your professional services on that day. The examination and refraction fall under the managed vision care contract, and the appropriate benefit structure is applied.

You direct the patient to return to the office for a full dry eye workup or ask her to return for evaluation of the topical agents you prescribed or recommended on the date of her visit; these additional office visits, and any procedures that you deem medically necessary and document in the record, could be covered by her medical plan. That may mean that she pays you in full because she has a high deductible that she hasn’t yet met, or she could simply be paying you a copay for the visit. In any case, it’s your responsibility to apply her contracted benefits accurately and in accordance with your contract agreement for that specific carrier.

Scenario Two

A patient calls the office and complains of fluctuating vision and irritated eyes. He has managed vision care and medical insurance.

In this scenario, the patient presented with frank symptoms of dry eye and therefore has met the chief complaint requirements of the medical carrier. You would code the encounter with either a 920X2 or a 992XX, depending on the status of the patient and the actual services provided and recorded in his file. This visit comes under the coverage umbrella of the medical carrier and, again, it’s your responsibility to follow the contractual guidelines for that specific carrier. The vision carrier is generally not involved, and the patient can’t use his managed vision care benefit for this visit even if it costs him less.

In each of these scenarios, if you follow the basic rules of the chief complaint and medical necessity, the party responsible for the economics of the encounter is readily apparent. Don’t let your emotions or feelings get in the way of you following the rules. Dry eye is exceedingly prevalent within our population, and you need to prepare your office to properly handle the diagnosis and long-term management.

Send questions and comments to [email protected]