|

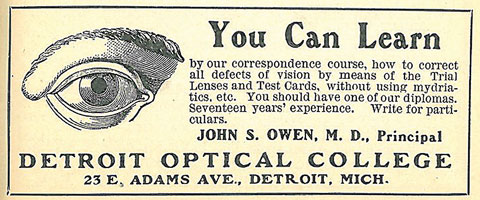

As with any profession, education has been instrumental in laying the groundwork for the evolution of optometry—but not without controversy. When optometry first emerged as a distinct profession in the 1890s, education was primarily through apprenticeship or privately owned schools—all without much, if any, regulation.1 Schools provided informal education, often in the form of short, two-week courses or correspondence courses.1 It didn’t take long for the early founders of the profession to realize that wasn’t going to cut it, and within two decades, many of these private schools served as foundations for what became more formalized institutions.2 The journey from those two-week courses in the early 1900s to the six-year experience of today is riddled with controversy, hard work and professional triumph.

Where it All Began

As the profession itself developed from one of jewelers and spectacle salesmen to refractionists and finally primary care providers, so too did the ivory towers grow to meet the needs of the profession and the public.3

The first pair of spectacles came to our shores in 1620, and over the next 250 years, optometry blossomed from an optical business into an invaluable health care profession.4 As the profession shifted to encompass more than spectacle dispensing, the need arose for more formalized education. The private schools of the late nineteenth century gave way to a more standardized curriculum as Columbia University’s School of Optometry, founded in 1910, became the first university-based school of optometry in the United States.1

By 1928, the New York Commissioner of Education saw the benefit of Columbia’s program and passed a bill allowing only graduates of a university-affiliated school of optometry to qualify for the state board exam. This signaled the end of the apprenticeship system of licensure and initiated a new era in optometric education.5

|

| The humble origins of optometric education. |

Optometric education began to boom, and several schools opened over the following decade, with the first public college of optometry, Ohio State University (OSU), being founded in 1914.1 Battles then ensued regarding the nature of the field’s growth and its correspondence to educational institutions.

Education Regulation

The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry chronicled the back-and-forth arguments regarding the direction optometric education should take. A 1934 retrospect by Dr. Thomas McBurnie sums up the confusion and dissonance apparent within the field: “for many years the question of optometric education has been discussed in its many phases by many of our optometric leaders with many varying viewpoints.”6 The biggest fight was how to gear education toward the professional advancement of the field, not simply the commercialization of the practice. Since its founding in 1898, the American Optometric Association (AOA) had as its mission to increase the professionalization and move away from the commercialization of optometry.

In his 1934 article, Dr. McBurnie supports the need within the AOA for a committee whose sole objective would be to take stock of these educational questions and “bring forth a definite program of education which would continue through the years and should not be hampered by the ever-changing administration of the AOA official body.”6 His call for a special committee gave rise to the Council on Optometric Education (COE) in 1925, which was comprised of volunteers tasked with accrediting optometric educational institutions. The COE was established in 1934 as the accrediting agency for OD education, with Dr. Charles Sheard at the helm. Later changing its name in 2001 to the Accreditation Council on Optometric Education (ACOE), this body is still in charge of accrediting optometric educational institutions.5

Recently, ASCO’s Committee on Attributes researched and developed competency statements regarding knowledge, skills and professionalism in 2000, and released a revision in 2011. The extensive list of attributes makes clear the expansion and development that has occurred over the last 125+ years with respect to optometrist’s demand, competency and capability.8,9 The foundations of today’s education took shape between 1935 and 1955, when a formal curriculum was developed—a six-year track comprising two years of liberal arts and four of specialized professional education.10

The next decade saw a boom in optometric education as evinced by OSU’s offering of a PhD degree in physiological optics under the direction of Dr. Glenn A. Fry.3

The Pros and Cons of Expansion

This expansion was met with excitement and reticence, as exhibited in a 1938 article in The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry that addressed the rapid progress of optometric education while cautioning for quality over quantity—stressing the importance of a more stringent rating system to provide “optometry with an academic place equal to other professions.”7 The tone of the discussion in the late 1930s is tellingly defensive, with one contributor arguing that, “we should not give up optometry to any other group or profession […] anyone desiring to practice optometry should qualify by taking the prescribed training and the state board examination for licensure.”7

|

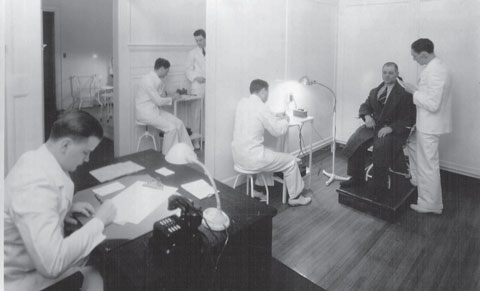

| A student clinic at PCO in the 1940s. Photo: Pennsylvania College of Optometry. |

An August 1937 article in Reader’s Digest lambasted the profession for its academic institutions and the state of its educational standards. The writer addresses the high number of optometrists he deems to have come from “inferior” or “extinct” institutions. “Higher requirements under state optometry laws […] reduced the number of recognized schools to eight,” he writes—further suggesting that, “on the face of the figures, the graduates of the better schools must be in the minority.”10 (see, “A Black Eye for Optometry”).

“In 1925, there were about 25 optometry schools, but efforts launched in the early 1920s to establish standards in optometric education decreased the number of schools to nine by 1927,” says David A. Goss, OD, PhD. “A leader in that standardization effort was an optometrist named Frederic Woll (1874-1955), who drew up syllabi of what should be covered in optometric curricula and visited schools in order to rate them.”

By 1941, Dr. Woll’s determination, and that of other eager practitioners, led to a new hurdle within the profession. “The eagerness to raise optometric educational standards has contributed to the problem of student supply,” The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry’s editor, Maurice E. Cox, wrote the same year.11

“The numbers of students in optometry schools dropped considerably during World War II, but there was a great influx of students after the war as veterans returned and attended school on the G.I. Bill,” Dr. Goss says. “The number of optometry school graduates swelled from a low of 157 in 1945 to 1,934 in 1949.” Edmund Richardson, president of the AOA, wrote in The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry in 1946 about his concern over the very large classes in school at that time.”12

From Projectors to PowerPointI love to reminisce to my students, “When I was your age we learned optometry by candlelight, reading cuneiform tablets in cold, dank rooms with no heat—and we had to walk uphill both ways with no shoes!” When I began teaching, most instructors used either the blackboard—with or without multi-colored chalk—or a projector with static-electricity-prone transparencies and a felt-tip marker. The advent of the computer allowed the ordinary professor to make real, professional academic slides, but when computers first came around, we all had to share. Getting your institution’s audio-visual specialist to help produce professional quality slides took great planning, money and a large buffer for turnaround. Clinical photos were taken with an anterior segment camera or fundus camera; sometimes it took weeks for the roll to be used up and developed. There was no checking to see if you got the shot. In fact, if someone lost the film, the developer made a mistake, the shot was out of focus or the patient blinked, ya got nuthin’! Once you had your slides, you had to store them in a plastic leaf and load them into a carousel just before the presentation or keep them permanently loaded in a dedicated carousel. Each method had advantages and disadvantages. Sleeves were cheap, and “sleevers” could travel light and reuse slides for different presentations. However, sleevers would often load in haste and put slides in upside-down or backwards. Slides could get lost or misfiled. “Carousellers” did not have those issues; they would load the carousel, double check it, label it and seal it forever. Very expensive. (I was a carouseller; I have no less than 20 of them gathering dust). What a nightmare for travel. And unless you had duplicates, once a slide was used it was out of the rotation. Research was no picnic either. There was no Internet; there were only scores of textbooks, bound journals and the card catalog. You could not do this from home, a coffee shop or anywhere else for that matter. It had to be done in your library. You had open books everywhere. The tables were 64 square feet and when you needed a reference you had to run around the table to find it. If you didn’t finish, it could take an hour to put everything away and an hour the next day to set it up again. Getting work published was also an exercise of will. There was no email. Each paper, complete with photos, diagrams and captions, had to be typed, double-spaced and copied in triplicate. They were mailed to the editor-in-chief (EIC), who distributed them to the referees. They wrote all over the copy and returned it to the EIC, who sent it back with a letter announcing the verdict: accepted or rejected. If you got accepted, corrections had to be made. Cut and paste was exactly that—you typed the corrections on a typewriter and then literally cut and pasted the changes into place. References were a nightmare. The Internet, laptops and digital cameras have made all of this obsolete. Now, you can make and edit slides on the spot; you can see each photo we shoot and can transfer them directly to the computer or printer. Research is accomplished using search engines with key terms and filters that narrow the field and find data quickly. Now there’s email for everything … easy peazy. I could go on about “the good ol’ days,” but space is limited. Anyway, if you are an old-timer like me, take some time to reminisce. If you’re a recent graduate, some day you’ll tell a similar story and claim the snow was colder and deeper. —Andrew S. Gurwood, OD, Pennsylvania College of Optometry |

The need for further exposure and new marketing techniques to promote growth in the field was not lost on the AOA, and public relations focused on an “enlarged opportunity for self-projection.”13 Of course, filling seats in the classroom had to coincide with an ever-improving curriculum.

Cox cited the AOA’s having consistently stressed the significance of the availability of optometric educational facilities and notes the steps optometry schools and colleges had taken to form an organization of their own to provide for regular inspection of the curriculum and institutions.13 The struggle between promoting the field and ensuring quality standards continued for decades.

Concerns Come Full Circle

Today’s suspicions about a glut of grads is nothing new. “From 1956 to 1965, the numbers of optometry school graduates were less than 400 each year,” Dr. Goss says. “By the late 1960s, some were suggesting that a perceived need for more optometrists should be met by a doubling of the number of schools from the 10 in the mid 1960s. In 1965, there were 377 graduates from 10 schools, which can be compared to [the] 1,404 graduates [from] 21 schools in 2012.” This growth in optometry—waxing and waning over the last century—has historically been met with varying approval.

The Story of Columbia UniversityBecause New York was the first to attempt to pass an optometry licensure law, it’s no surprise that it also became home to the first optometry school affiliated with a university.1 New York successfully passed an optometry law in 1908, and Columbia University School of Optometry began just two years later in 1910.2 Charles Prentice himself formulated the course, which included general physics, anatomy and physiology of the eye, theoretic optometry, pathologic conditions of the eye and practical optometry, to name a few.2,3 Another founding father, Andrew Cross, became the school’s first active director.3 The program only had to enroll 12 students, but the first class was already robust at 21.2 It was an immediate success, and the inaugural class submitted a letter of thanks to The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry in December to “extend their thanks and grateful appreciation for the invaluable services [the school has] rendered in behalf of the profession.”2 The Optical Journal-Review also published an editorial in 1910, stating “Now that Columbia University is to give a course in optometry, optometrists of those States which are not near to the site of this institution are discussing the need of getting the universities of their localities to put in a similar course.”2 Such immediate notoriety illustrates its pivotal role in the history of the profession. Although those seeking an optometric education held the school in high esteem, continual pressure from ophthalmology eventually led to the school’s closure in 1954. The alumni organized an immediate protest, claiming the university “failed the people of the state of New York by cutting off the source from which stemmed some great contributions to the science of vision.”4 Later that year, in an attempt to fill the educational void in New York, a small group of optometrists founded the Optometric Center of New York (OCNY), a nonprofit health and education resource.5 It took more than a decade of lobbying before the New York State Legislature voted to establish a new college of optometry. The State University of New York (SUNY) College of Optometry enrolled its first class in September 1971, and has been a powerhouse of education ever since.

|

In 1937, Mr. Cox argues that, “while on the one hand optometry is greatly undermanned, on the other the profession appears to have an overstock of the wrong kind of material. Specifically, [that] too many of those coming into optometry do not have the proper professional concept.”14 This argument could easily be transposed to contemporary concerns within the field. Today, with 25 optometry schools to choose from, many dredge up the age-old argument about quality over quantity. The debate over the 2016 opening of University of Pikeville-Kentucky College of Optometry, for example, is eerily similar to concerns voiced over the last 125 years.

“Acceptance rates for medicine and other health care professions are around 40%, and at the moment, optometry has an acceptance rate of 70%,” Dominick Maino, OD, MEd, a professor at Illinois College of Optometry, says in a recent Review of Optometry news article. “Although this has not appeared to affect the quality of our entering classes, at some point I would suspect that quality will suffer.”15

KYCO capitalizes on its geographic location with aims to meet a public health need in an underserved area; yet, several ODs expressed disapproval about opening a new optometry college and trying to fill classes with qualified students and overcrowding in the field—the same story from 1937 come back to life.

Growth, however, continues despite the reoccurring arguments regarding the oft-perceived fraught future of the profession. Optometry’s educational history may continue to repeat itself as each new school opens its doors, sparking the new-old debate where the heart of the future exposes its age-old roots. But the undeniable progress leaves optometry solidly recognized as an integral sect of the medical field.

|

1. Goss DA. Landmarks in the history of optometry. Hindsight: Journal of Optometry History. 2007;38(2):47-52. 2. Book on the history of the Illinois College of Optometry. Hindsight: Newsletter of the Optometric Historical Society. 1998;29(4). 3. Shaver DV. Opticianry, optometry, and ophthalmology: an overview. Medical Care. 1974;12(9):754-65. 4. Register SJ. A backward glance on optometric educational Institutional profile of schools and colleges of optometry. Optometric Education. 2011;36(2):76-81. 5. AOA website. AOA historical timeline. http://fs.aoa.org/optometry-archives/optometry-timeline.html. Accessed April 1, 2016. 6. McBurnie T. The AOA year in retrospect. The optical journal and review of optometry. The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry. 1934 July:22-5. 7. Folsom LP. Our educational problems. The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry. 1938 July:14-5. 8. Optometric education. Attributes of students graduating from schools and colleges of optometry: An Association of Schools and Colleges report. 2000;26(1):15-19. 9. Attributes of Students Graduating from Schools and Colleges of Optometry: A 2011 Report from the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry. 2011. 10. Riis RW. Optometry on trial. Reader’s Digest. Aug 1937;31(184):77-85. 11.Cox ME. Sustaining and projecting optometry. The optical journal and review of optometry. 1941;78(14):34-7. 12. Richardson E. The optical journal and review of optometry. 1946;83(22):46-51. 13. Hirsch MJ, Wick R. The optometric profession. New York: Chilton Book Company, 1968. 14. Cox ME. A little more selectivity. The optical journal and review of optometry. Sept 1937:20-1. 15. Hepp R. New OD school debut sparks debate. Review of Optometry. 2016;153(1):6. |