|

A 92-year-old Hispanic male presented to our institute for acute vision loss and new floaters for one week in the left eye (OS). Past ocular history included cataract surgery OS in 2008 and strabismic amblyopia in the right eye (OD) since childhood. Medical history included benign prostatic hyperplasia, hypercholesterolemia and hypothyroidism, all of which were controlled medically.

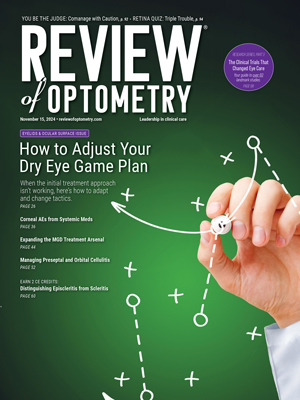

Entering visual acuity (VA) was counting fingers OD and 20/150 OS with pinhole improvement to 20/100. Intraocular pressures were 16mm Hg OD and 14mm Hg OS. His extraocular motilities were full and his pupils were equally round and reactive without a relative afferent pupillary defect. Slit lamp exam revealed a cataract OD and well-positioned intraocular lens OS with posterior capsular opacification. Fundus imaging is available for review.

|

|

Fig. 1. Optos widefield fundus photos of the right eye (A) and left eye (B). Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

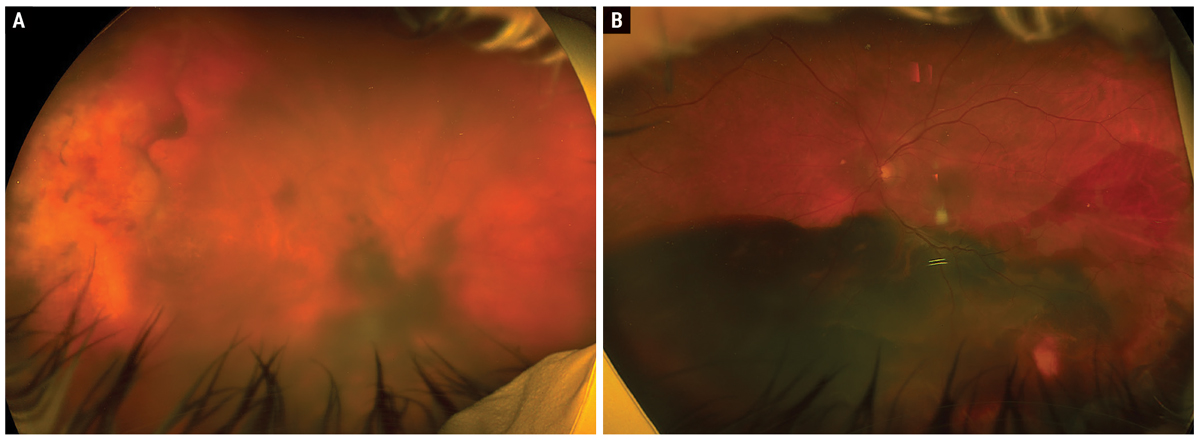

1. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the left eye shows that the hemorrhage is located in what space?

a. Vitreous cavity.

b. Sub-internal limiting membrane.

c. Subretinal.

d. Subretinal pigment epithelium.

2. What is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Choroidal melanoma.

b. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy.

c. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.

d. Ruptured retinal arterial microaneurysm.

3. Which of the following is FALSE regarding this patient’s disease?

a. It is often asymptomatic.

b. Lesions often present between the posterior pole and equator.

c. It is often bilateral.

d. The mean age of patients is about 80 years.

4. Which of the following is TRUE regarding management of this disease?

a. Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections are used when lesions are progressive and threaten the macula.

b. Observation is elected when lesions involve the periphery and patients are asymptomatic.

c. Vitrectomy is a reasonable option for non-clearing vitreous hemorrhages.

d. All of the above are true.

5. What is the general prognosis for this disease?

a. Prognosis is excellent, as all cases resolve without permanent visual deficits.

b. Prognosis is overall good, as many cases spontaneously regress in absence of treatment.

c. Prognosis is fair, as most cases will progress but respond to treatment.

d. Prognosis is guarded, as most cases progress despite treatment.

|

|

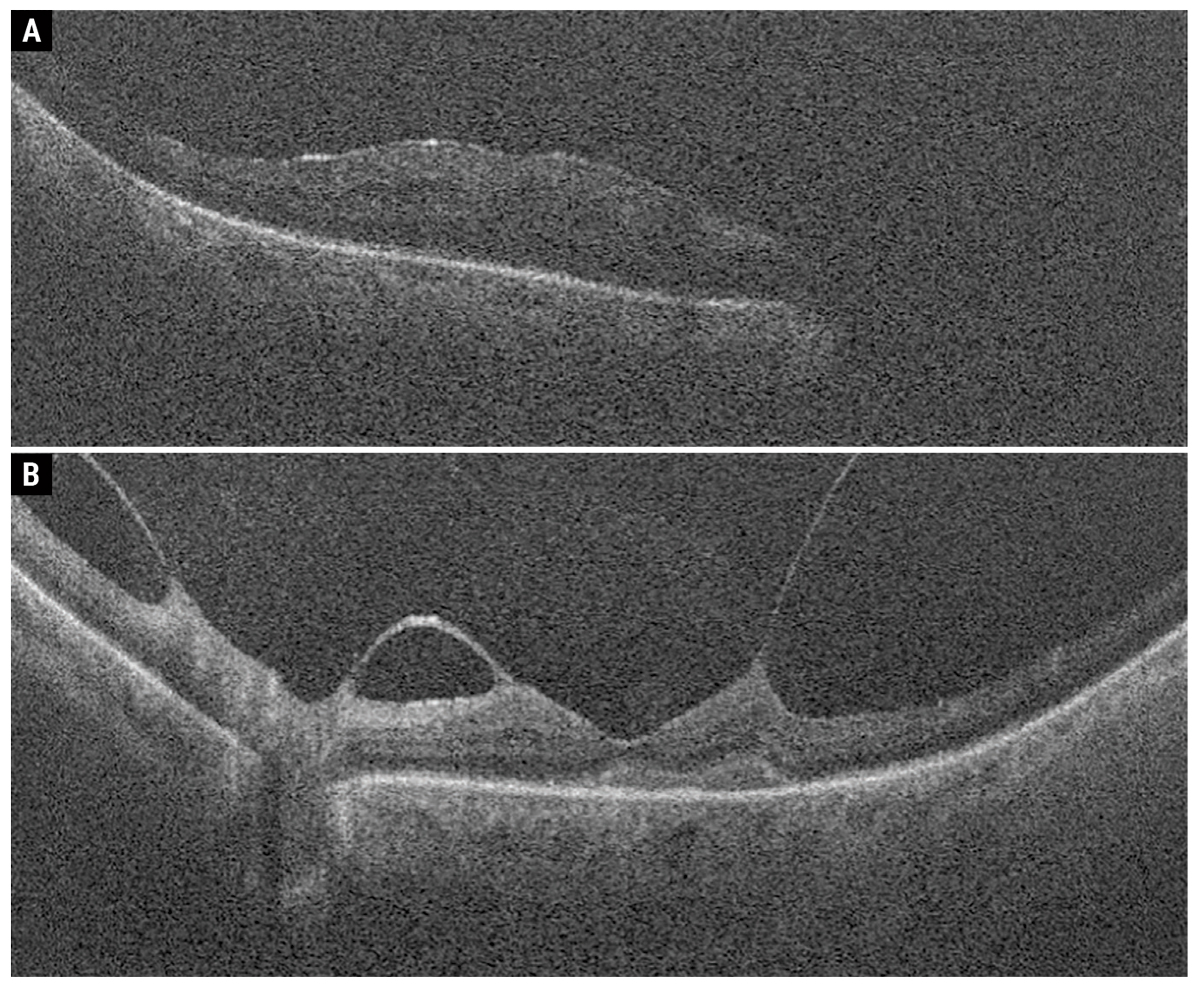

Fig. 2. Macular OCT of OD (A) and OS (B), as well as eccentric OCT over inferior macula OS (C). Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

Fundus examination disclosed a vitreous hemorrhage (VH) OD and bilateral peripheral hemorrhagic lesions with extensive subretinal hemorrhage OS>OD involving the macula OU (Figure 1A and B). Macular OCT showed an epiretinal membrane with intraretinal fluid OD (Figure 2A) and vitreomacular traction with heterogeneous subretinal hyper-reflective material involving the fovea extending inferiorly throughout the macula OS (Figure 2B and C). B-scan ultrasonography was obtained to rule out underlying choroidal etiology and further demonstrated the extent of subretinal hemorrhage OU. A diagnosis of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy was made, and the patient received intravitreal bevacizumab OU given foveal involvement.

|

|

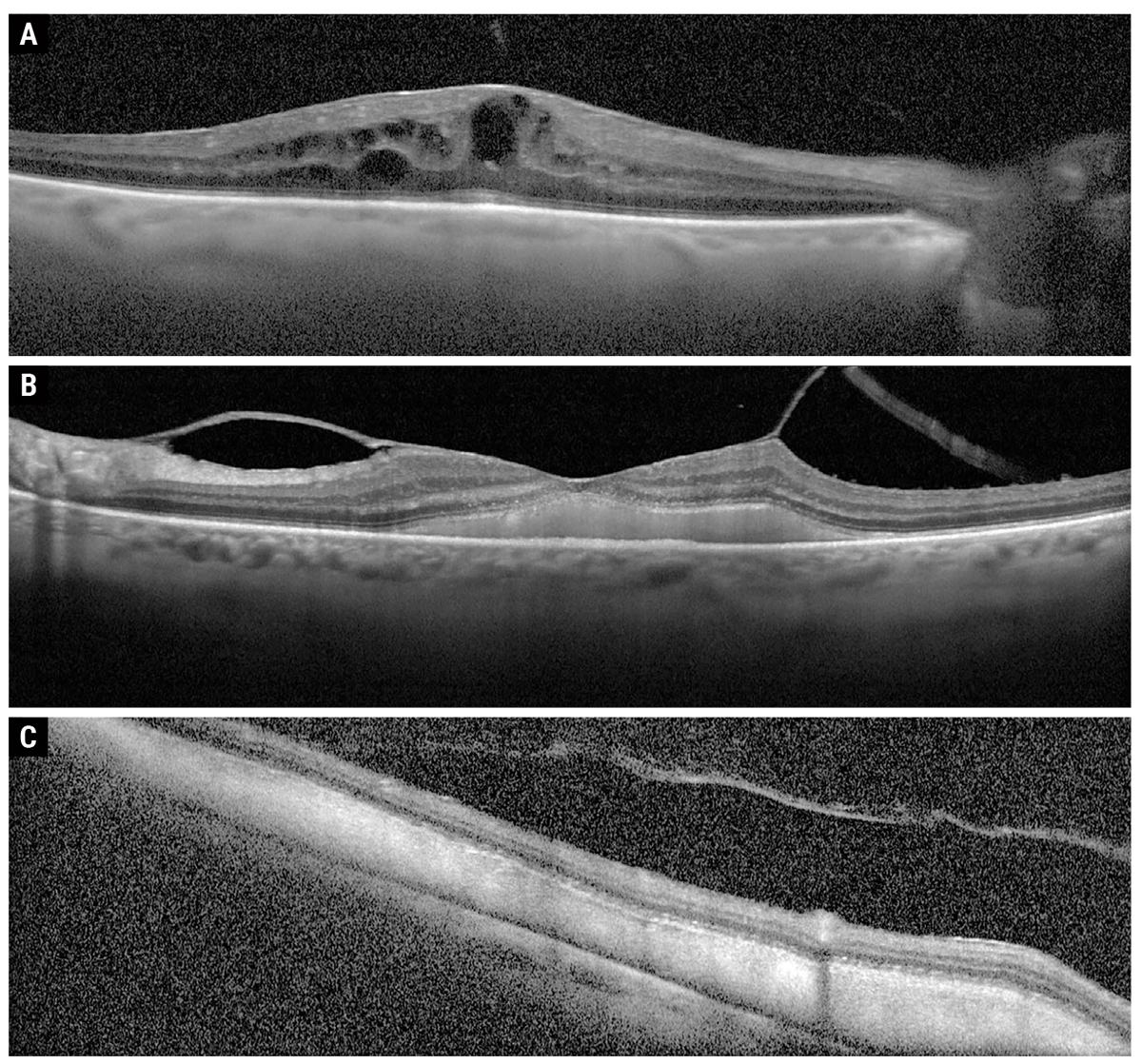

Fig. 3. One-month follow-up Optos fundus photos of the right eye (A) and left eye (B). Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) is a rare, bilateral, peripheral exudative-hemorrhagic retinal degeneration that typically occurs between the equatorial fundus and ora serrata.1,2 Up to 100% of patients are reported to be

Caucasian and 67% to 69% female, with a mean age at presentation of 77 to 80 years old (range 57 to 97).1-4 Interestingly, only about half of patients are symptomatic and only 20% have a reduction in VA; there is likely underrepresentation of the disease entity due to initial extrafoveal involvement during the acute phase.1,4,5

Symptoms are often due to extension of the peripheral hemorrhage into/toward the macula and/or breakthrough hemorrhage into the vitreous cavity.2,3 The PEHCR lesion is found in the temporal fundus in 77% of eyes, spans one to two quadrants in 92% of eyes and is located between the equator and ora serrata in 89% of eyes.4 More specifically, lesions are most frequently present inferotemporally (56%), followed by superotemporally (40%), superonasally (24%) and inferonasally (20%).3

PEHCR can be categorized as hemorrhagic (63%), exudative (6%) or exudative-hemorrhagic (31%).3 Isolated exudation appears as yellow-white material, and the combined exudative-hemorrhagic form has a more reddish orange-brown coloration as the lipid mixes with the blood.3 Subretinal hemorrhage may appear heterogeneously bright red to dark red (sometimes almost black, depending on thickness of blood accumulation) with poorly demarcated edges.3 In contrast, subretinal pigment epithelial (RPE) hemorrhages tend to appear more uniformly dark red-to-brown/gray/black with larger dome-shaped elevations and more well-demarcated margins.3,5 One study has reported VH was present in 7% of affected eyes.4

PEHCR is a clinical diagnosis based on characteristic fundus features. Fluorescein angiography (FA) is of little diagnostic utility in this disease due to blockage from overlying subretinal and sub-RPE hemorrhage as well as secondary RPE hyperplasia.1,5 However, indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) may have more use locating the neovascular lesion, which is often near the border of hemorrhage.1 PEHCR is thought to be on the spectrum of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV); in particular, the exudative lesion in PEHCR resembles polyps seen in PCV on ICGA.2,5

When vitreous hemorrhage is present, B-scan ultrasonography can demarcate the area of involvement and better characterize the lesion.3-5 Importantly, B-scan features of PECHR include a retraction cleft, as well as greater internal reflectivity, greater echogenicity and heterogeneity, and absence of mushroom configuration as compared with uveal melanoma.4

|

|

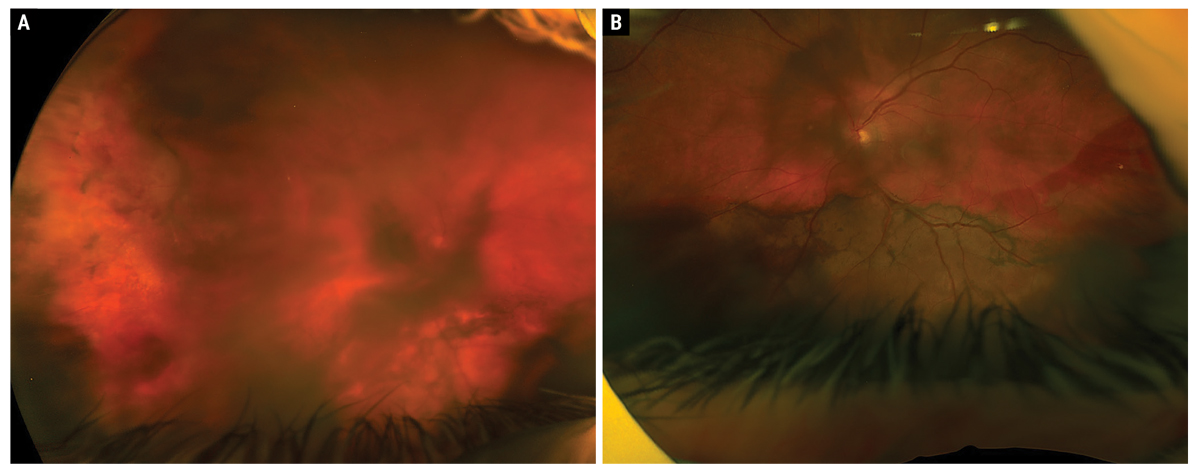

Fig. 4. Macular OCT scans of the right eye (A) and left eye (B). Click image to enlarge. |

The differential diagnosis includes choroidal nevus, choroidal hemangioma, choroidal/ciliochoroidal melanoma, choroidal/ciliochoroidal detachment, PCV, retinal arterial microaneurysm and retinal detachment. Of note, uveal melanoma is the most significant differential diagnosis and the most frequent presumptive diagnosis that these patients are referred to a specialist with; furthermore, PEHCR is the second-most common pseudomelanoma following choroidal nevus.1,2,4 It is critical to distinguish between PEHCR and uveal melanoma, as a timely and accurate diagnosis can avoid unnecessary radiotherapy and/or enucleation.

Management and Prognosis

To date, there are no randomized trials investigating appropriate management of these patients. Prognosis is generally good when sparing the macula, as one study demonstrated in a retrospective series of 90 cases that 89% improved or remained stable with observation alone, and only 11% worsened.4,6,7 Therefore, observation is a reasonable management option, though patients should be followed closely, as progressive hemorrhage and/or exudation may threaten both peripheral and central vision.4,7 When it is macula-involving, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections are the mainstay of modern treatment for this disease; however, visual recovery may be limited based on extent and duration of hemorrhage or exudation.2,4,7 Pars plana vitrectomy may be considered in patients with non-clearing VH.4

Our patient received intravitreal bevacizumab OU. At one-month follow-up, he demonstrated reduction in intraretinal fluid OD and subretinal hemorrhage OS with stable VA OU (Figures 3 and 4). He was recommended a second intravitreal bevacizumab injection OU at follow-up but declined due lack of subjective improvement experienced from the prior injection. The patient was recommended to maintain close observation but was ultimately lost to follow-up.

Retina Quiz Answers

1: c, 2: b, 3: b, 4: d, 5:b

Dr. Aboumourad currently practices at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. He has no financial disclosures.

1. Ryan SJ, Davis JL, Flynn HW, et al. Retina. Fifth ed. Saunders/Elsevier; 2013. 2. Elwood KF, Richards PJ, Schildroth KR, Mititelu M. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR): diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(9). 3. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-64. 4. Shields CL, Salazar PF, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy simulating choroidal melanoma in 173 eyes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):529-35. 5. Mazal Z. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2019;75(2):80-4. 6. Vandefonteyne S, Caujolle JP, Rosier L, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of peripheral exudative haemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(6):874-8. 7. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-9. |