Differentiating Problems of the Eyelids and Ocular Adnexa

When patients ask about dermatologic concerns around the eyes, be prepared to address them in the office and refer when needed.

By Marlon J. Demeritt, OD, and Beata I. Lewandowska, OD

|

Release Date: February 15, 2020

Expiration Date: February 15, 2023

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: 2 hours

Jointly provided by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and Review Education Group

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Recognize common dermatological conditions and how to differentiate between them.

- Take a good clinical history to help hone the diagnosis.

- Describe when and how to refer.

- Discuss the basics of treating these common dermatological conditions in the office.

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in the care of patients with dermatological conditions of the eyelids and adnexa.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Review Education Group. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, and the American Nurses Credentialing Center, to provide continuing education for the healthcare team. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is accredited by COPE to provide continuing education to optometrists.

Faculty/Editorial Board: Marlon Demeritt, OD, and Beata Lewandowska, OD.

Credit Statement: This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. Course ID is 66534-GO. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statements:

Drs. Demeritt and Lewandowska have nothing to disclose.

Managers and Editorial Staff: The PIM planners and managers have nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group planners, managers and editorial staff have nothing to disclose.

To the general population, lesions of the eyelid skin are often a cosmetic, not a medical, concern. While ophthalmologists, and optometrists in numerous states, can surgically address the cosmetic issues of eyelid lesions, the primary concern is whether the lesion in question is benign or malignant in nature and whether it warrants a referral.

Clinical decision making is guided by the pertinent information gathered about the patient’s medical history; thus, effective communication is a critical aspect of a successful physician-patient encounter. Careful history taking and examination can reveal important clues when suspecting malignancy of eyelid lesions.

|

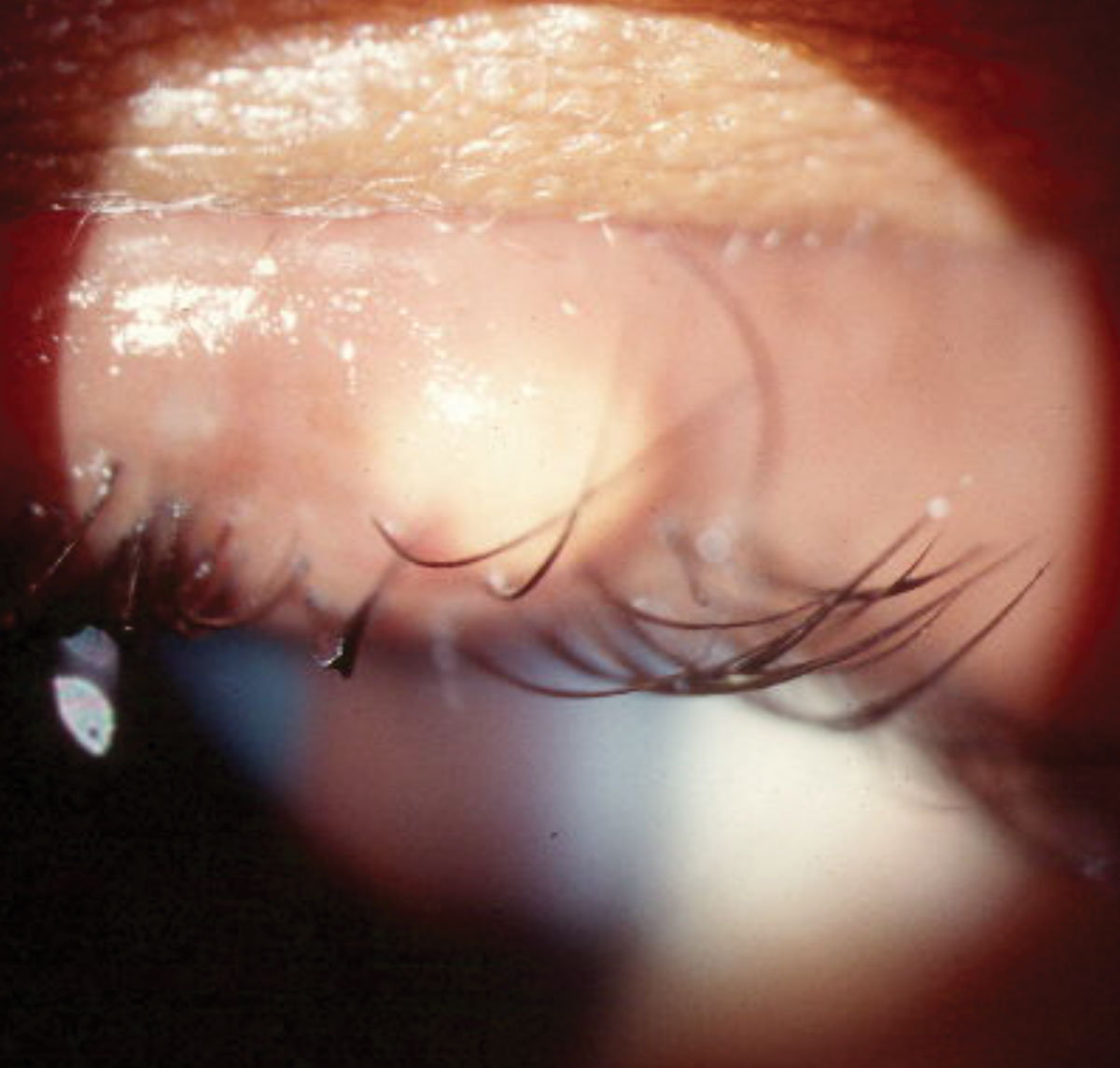

| Fig. 1. Localized swelling secondary to an external hordeolum pointing anteriorly through the eyelid skin. Photo: Diana Shechtman, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The most common risk factors for developing skin cancer include fair skin, previous skin cancer, smoking, excessive sun exposure, prior radiation and immunosuppression.1 To reveal these risk factors in a patient’s history, clinicians can ask these questions:

- When did you first notice the lesion?

- Has the lesion changed in color, size or shape?

- Has the lesion caused you any pain or irritation?

- Has the lesion caused bleeding or draining of fluid or purulent material?

- Have you noticed any other similar skin lesions on other parts of your body?

- Have you had similar lesions on your eyelids in the past?

- Do you have a history of skin cancer?

When to Refer

The decision to refer depends on various factors, such as the risk of malignancy and the cosmetic concern of the patient. Malignancy is and should be the primary concern of the provider and the patient. Any of the following signs and symptoms are suspicious and warrant referral:

- The lesion violates the ABCDE rule (Table 1).

- The lesion becomes ulcerated, bleeds or loses eyelashes.

- The lesion changes color.

- The patient notices growth after onset.

- The borders of the lesion assume an irregular shape.

- Risk factors exist that indicate suspicion for malignancy.

Non-malignant Issues

Once malignancy has been ruled out, there are a number of common non-malignant dermatologic findings you might encounter in your practice (Table 2). Many of these conditions have similar presentations. Here’s a look at how to differentiate each one (Table 3).

Cysts are benign, painless focal blockages of the glands that can occur on the palpebral conjunctiva or the skin of the eyelid. Cysts of Moll, dome-shaped papules or nodules filled with clear fluid that transilluminates, are the result of blocked apocrine sweat glands. The secretory cells of Moll can give rise to bluish adenomas, which are known as apocrine hidrocystomas. Blocked sebaceous glands will give rise to a cyst of Zeiss, which, unlike cysts of Moll, will not transilluminate, as they are filled with a yellow oil-like secretion. Epidermal inclusion cysts, which tend to be elevated, round, keratin-filled, firm lesions, arise from an occlusion of the infundibulum of the hair follicle. These cysts are often slow-growing and may have a central pore. They require surgical excision.

Hordeola, which usually present as swollen, red and painful lesions, are secondary to acute bacterial infections. According to recent studies, 90% of hordeola are associated with Staphylococcus aureus.2 Internal hordeola originate in the meibomian glands while external hordeola originate in the glands of Zeiss or Moll.3 Patients at risk for developing a hordeolum are those with a history of poor lid hygiene or inflammatory diseases of the eyelid such as blepharitis, rosacea and meibomitis.4,5

Table 1. The ABCDEs of Melanoma55 | |

| A = asymmetry | Malignant lesions tend to be asymmetric. |

| B = border | Malignant lesions tend to have irregular, scalloped and poorly defined borders. |

| C = color | Malignant lesions tend to vary in color from one area to another. |

| D = diameter | Melanomas are usually greater than 6mm at the time of diagnosis. |

| E = evolution | Malignant lesions tend to evolve and will change over time in aspects of shape, size and color. |

Table 2. Dermatological Terms | |

| Cyst | A closed sac that contains liquid/semisolid material, usually resilient on palpation. |

| Papule | A solid, elevated lesion with no visible fluid; up to 0.50cm in diameter. |

| Nodule | A larger and deeper papule that may be in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue, or in the epidermis; usually 0.50cm or more in diameter. |

| Pustule | A circumscribed elevation containing a purulent exudate (white, yellow or greenish-yellow). |

| Vesicle | A circumscribed epidermal elevation containing clear fluid; less than 0.50cm in diameter. |

Table 3. Dermatological Differential Diagnoses | |

| Papilloma | Verrucae vulgaris, seborrheic keratosis, verrucous carcinoma |

| Hordeola | Preseptal cellulitis, sebaceous gland carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, chalazion |

| Molluscum contagiosum | Papilloma, verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, herpes simplex, herpes zoster |

| Contact dermatitis | Rosacea, atopic eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, blepharitis, psoriasis |

| Preseptal cellulitis | Orbital cellulitis, chalazion, hordeola, viral conjunctivitis, eyelid abscess |

| Orbital cellulitis | Preseptal cellulitis, orbital tumors, orbital pseudotumor, thyroid eye disease, mucormycosis |

| Ocular rosacea | Posterior blepharitis, contact dermatitis |

| Impetigo | Herpes simplex dermatitis, discoid lupus erythematosus, cutaneous candidiasis |

| Herpes zoster ophthalmicus | Herpes simplex, contact dermatitis, rosacea |

The common approach to managing hordeola involves observation in cases where the lesion is smaller in size and the patient is asymptomatic (Figure 1). Daily lid hygiene as well as topical and systemic antibiotics can be used in situations where size, cosmesis or discomfort are a problem. Topical steroids can be effective in reducing healing time and symptoms associated with inflammation.6,7

Recurrent hordeola can occur due to failure of complete bacteria eradication.8 A recurrent hordeolum or chalazion—a similar lesion caused by a clogged oil gland—in the same area should prompt the clinician to suspect sebaceous gland carcinoma. One study reported sebaceous gland carcinoma as the most commonly missed malignancy, oftentimes misdiagnosed as a chalazion.9

Sebaceous gland carcinoma, an aggressive neoplasm with possible local and distant metastasis, has a higher rate of morbidity and 5% to 38% mortality.10 Recurrent hordeola or chalazia should be considered suspicious in nature and should be referred for biopsy.

The term papilloma encompasses a group of various benign epithelial skin lesions. Most commonly, a benign squamous papilloma is an elevated, smooth, rounded, sessile or pedunculated, flesh-colored lesion often found on the eyelid skin. These lesions may be treated with either cryotherapy or surgical excision.

Verruca vulgaris, also known as a viral wart, is a common benign cutaneous lesion caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV).1 These lesions have different shapes, sizes and levels of pigmentation. They appear as hyperkeratotic papules with a rough, irregular surface. Filiform warts are long, slender growths often found on the eyelid skin. Verrucae affecting the eyelids are usually asymptomatic and can be observed (Figure 2). In some cases, they may cause cosmetic disfigurement, which would warrant surgical excision.

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by viral infection of the skin (Figure 3). On clinical exam, expect to see a solitary lesion or multiple lesions that appear as umbilicated papules that are pink or skin-colored.11,12 Small, solitary lesions are generally seen in immunocompetent patients, while the immunosuppressed patient will have larger (greater than 1cm) and more extensive papules.13-15 Transmission of the virus occurs through direct contact with infected skin, contaminated towels or even swimming in a pool.16 Although you can see molluscum contagiosum in an immunocompetent patient, the molluscum poxvirus is more common in immunocompromised patients, with the prevalence in HIV patients close to 20%.17 Ophthalmic lesions from MC are common on the lid margin and can lead to chronic follicular conjunctivitis due to the shedding of viral particles into the tear film.18-20

While evaluating a patient with conjunctivitis, these lesions can be overlooked, especially when the patient seems healthy. Because these lid lesions can be implicated as causes of follicular conjunctivitis, a careful dermatological evaluation of the eyelids is essential. Patients with the molluscum virus may develop eczematous plaques around one or more lesions, which is known as molluscum dermatitis. Approximately 9% to 47% of patients with molluscum will develop this condition; however, unlike allergic contact dermatitis, there is no clear consensus if the application of topical steroids facilitates resolution of the molluscum lesions.21-23

Molluscum contagiosum lesions are usually self-limiting, with a duration of six to nine months. Still, in some cases the duration can span three to four years.24 In immunosuppressed patients, the condition is usually refractory to treatment.15

Treatment options include observation, antiviral medications, curettage, immunomodulators and specific chemicals, such as cantharidin and 10% potassium hydroxide, targeted at destroying the lesion.

In an immunocompetent patient with a solitary lesion, it is likely safe to monitor the patient for up to nine months. Once the patient develops a follicular conjunctivitis secondary to the lesion, a referral to an oculoplastic surgeon is warranted.

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory condition of the skin that is precipitated by exposure to an offending agent that produces an allergic response.25

Two types exist: an irritant contact dermatitis and an allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Here, we will focus our attention on ACD. The mediation of skin inflammation occurs due to activation of antigen-specific acquired immunity. The activation of the acquired immunity leads to the development of effector T cells.26 Activation of effector T cells leads to the inflammatory process responsible for the cutaneous lesions and occurrence of ACD.26,27

The patient may complain of itching and swelling of the eyelids and around the eyes. The case history will uncover recent exposure to the offending allergen responsible for the reaction. The periorbital area will reveal swelling and erythema of the eyelids and, in some cases, a scaly appearance on the ocular adnexa. If all four eyelids are involved, allergic contact dermatitis is very likely the diagnosis.28 If uncertain of the diagnosis, you may refer your patient to a dermatologist for a patch test.

|

| Fig. 2. Asymptomatic filiform verruca with a typical irregular surface. Photo: Diana Shechtman, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

If the offending agent is known, eliminate contact with it, and if no contraindications are present, initiate a topical steroid cream for management of the dermatitis. It is important to keep in mind that, although rare, some patients may be allergic to the preservatives used in the base of the steroid cream. In addition, topical steroids carry a risk of skin atrophy as well as hypo- and hyperpigmentation. For cases unresponsive to conservative management, consider referral to a dermatologist.

Preseptal and orbital are the two types of cellulitis you may encounter in clinical practice. While the former involves an infection of the anterior portion of the eyelid, the latter is an infection of the contents of the orbit, which include periorbital fat, extraocular muscles and neurovascular bundles.29,30 Initially, the two conditions may appear indistinguishable. Fortunately, preseptal cellulitis is more common than orbital cellulitis. Preseptal can progress to orbital cellulitis, which is usually associated with high mortality rates.31,32

To properly distinguish between preseptal and orbital cellulitis, clinicians should obtain a good history, evaluate the patient and order laboratory testing and imaging studies.33 During the history, inquire about when symptoms started and whether the patient is experiencing any reduced vision, double vision, pain or fever. Patients with orbital cellulitis may present with a recent acute sinusitis or a history of upper respiratory tract infection.33

While patients with preseptal usually present with sudden-onset redness, swelling, eye pain and mild fever, patients with orbital cellulitis may have limited extraocular movements, pain, decreased vision, diplopia and proptosis.34,35 Imaging studies in the form of a CT scan should be performed within 24 hours, if there is no improvement with antibiotic therapy or if there is a deterioration of the patient’s condition.29,36

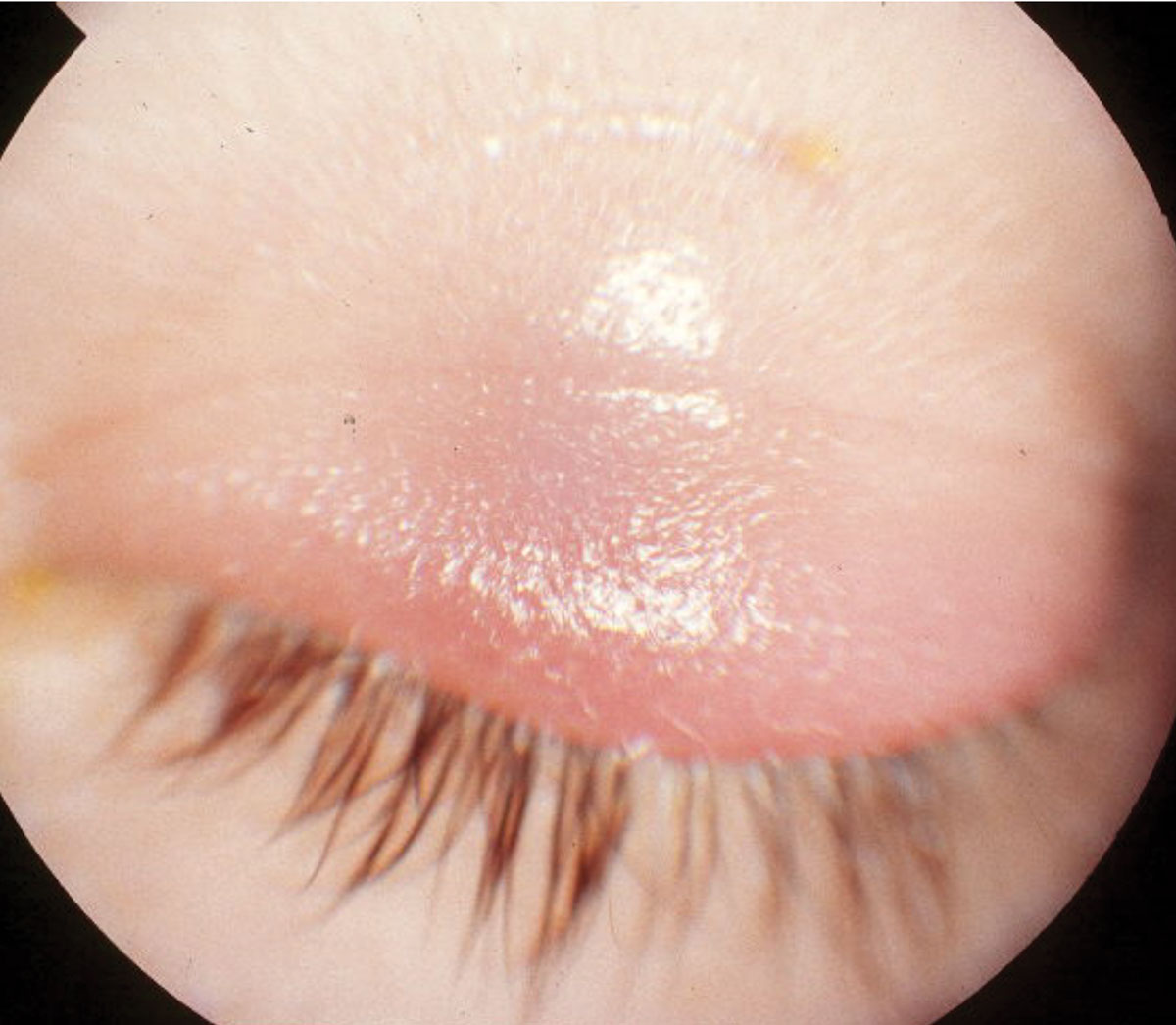

Generally, empirical treatment is initiated with broad-spectrum oral antibiotics to manage the preseptal cellulitis (Figure 4). Orbital cellulitis can be life- and vision-threatening, so prompt diagnosis and management are crucial. Most patients require hospital admission when the following signs are present: periorbital swelling, decreased vision, double vision, abnormal pupillary responses, proptosis, restricted ocular motility, headache, seizures, vomiting and drowsiness.36 Management of orbital cellulitis involves an intravenous antibiotic for one to two weeks, followed by oral antibiotics for four weeks.37

|

| Fig. 3. This is an example of a single solitary skin colored Molluscum contagiosum lesion with an umbilicated center. Click image to enlarge. |

|

| Fig. 4. This child had swelling of the upper eyelid in a case of preseptal cellulitis, which can generally be managed with broad- spectrum oral antibiotics. Click image to enlarge. |

Impetigo is a term used to describe an infection caused by Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus in the superficial keratin layer of the skin. It often presents in socioeconomically disadvantaged children between the ages of two and five as discrete purulent lesions of the eyelid skin.38 These lesions begin as papules, then rapidly evolve into vesicles surrounded by skin erythema. The lesions gradually enlarge into pustules before breaking down over four to six days to form thick crusts.

Treatment involves systemic penicillinase-resistant penicillins or first-generation cephalosporins.

Altabax (retapamulin) 1% topical antibiotic ointment is FDA approved for children nine months or older and should be applied BID for five days.38 Improved personal hygiene and improved living conditions are also recommended.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition of the skin that affects the facial and ocular regions (Figure 5). Typically, rosacea affects patients between 40 and 59 years of age.39 The National Rosacea Society estimates that 16 million Americans have acne rosacea, and 58% to 72% of acne rosacea patients also suffer from ocular symptoms.40 There are four distinct subtypes describing varying degrees of inflammation. Subtypes I, II and III are classified as erythematelangiectatic rosacea, papulopustular rosacea or phymatous rosacea, respectively.41 Ocular rosacea is classified as the fourth subtype.41

Ocular involvement can occur concomitantly or independently of the facial features of redness overlying the patient’s nose and cheeks.42 The dermatologic reaction associated with rosacea results in meibomian gland dysfunction, scarring of the meibomian gland orifices and telangiectasia of the eyelid margin.43-47 This can lead to the reduction in the efficiency of the lipid layer, which causes the patient’s vision to become compromised due to an unstable tear film, thus contributing to symptoms of ocular dryness. It is not uncommon for severe cases of rosacea to lead to ocular surface conditions, such as recurrent corneal erosions, ulceration and corneal perforations.43,46,48

Various approaches to the management of rosacea exist, such as lifestyle modification, conservative therapies, medical management, surgical management and laser therapy. Conservative treatments such as lid hygiene facilitate improved outflow through the meibomian glands and stabilization of the ocular surface.49

Medical management includes the use of artificial tears, nutritional supplements, immunosuppressive agents, antibiotics and antimicrobials. Symptoms of dry eye are common with rosacea because of its effect on the meibomian glands. Artificial tears are helpful in ameliorating the symptoms of dry eye due to ocular rosacea, but twice-a-day instillation of cyclosporine A has proven to be more efficacious than artificial tears.50

Included in our armamentarium of treatment options are antibiotics, specifically oral doxycycline, with several authorities suggesting that antibiotics become a constant in the management of ocular rosacea.49,51 Laser and surgical treatment options are also possible, and patients should be referred to dermatology for these. Intense pulsed light is an emerging treatment for rosacea and, off-label, meibomian gland dysfunction. The procedure involves direct application of light of appropriate wavelengths to the skin; research shows that it improves tear break-up time and patient symptoms as well as reduces skin erythema and telangectasia of rosacea.52,53

Table 4. Systemic Antiviral Medications for the Treatment of Herpes Zoster56,57 | |

| Acyclovir* | 800mg five times per day PO |

| Valacyclovir* | 1,000mg TID PO |

| Famciclovir* | 500mg TID PO |

| *seven-day dosage | |

Careful evaluation and proper treatment of patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus are crucial to decrease long-term morbidity and incidence of postherpetic neuralgia. When human herpesvirus type 3 reactivates in the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, pain and a breakout of cutaneous pustules will often cause the patient to rush to the office. This can occur in one or multiple areas that include the forehead skin, eyebrow, eyelid and the skin at the side of the tip of the nose (Hutchinson’s sign). Between 50% and 72% of patients will demonstrate ocular involvement with eyelid rash or, in more severe cases, corneal epithelial and stromal involvement, optic neuritis, uveitis or retinal necrosis.54

Initially, the pain is often a mild burning and tingling sensation, known as a prodrome, but as the body’s inflammatory response becomes more severe, the pain becomes more intense. The eyelids will typically manifest a rash that may develop a secondary bacterial infection resulting in yellowing, crusting and discharge.

A corneal pseudodendrite of heaped-up epithelium that exhibits “negative staining” by collecting the fluorescein stain at its edges may be present. Using rose bengal or lissamine green vital dyes can assist in differentiating between a pseudodendrite and dendritic lesion secondary to herpes simplex virus.

Anterior stromal keratitis with stromal infiltrates may coalesce to form a nummular keratitis. Infection of the corneal endothelium may present with a stromal keratitis and elevated intraocular pressure due to a trabeculitis.

If the patient is immunocompromised, rapid necrotic inflammation of the retina may develop, often leading to permanent vision loss. Therefore, a thorough medical history and a complete ophthalmic examination with a dilated retinal fundus exam is indicated in these patients. The most common chronic complication of herpes zoster infection is postherpetic neuralgia, consisting of severe, debilitating pain that may persist indefinitely and is seen in 9% to 45% of cases.54

|

| Fig. 5. This patient presented with facial features of rosacea, including redness of the nose and cheeks extending into the forehead. Photo: Diana Shechtman, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

All patients presenting with herpes zoster ophthalmicus require treatment with systemic antiviral medications (Table 4). Evidence shows that therapy with oral antiviral medications started within 72 hours after the onset of rash can reduce the duration of viral shedding, promote resolution of skin lesions and limit the duration of pain.54 Artificial tears to lubricate the ocular surface and a topical ophthalmic antibiotic ointment used four times a day to prevent a superinfection should be considered. Topical steroids are helpful in stromal keratitis, uveitis and episcleritis/scleritis, but caution should be exercised if an epithelial defect is still present. Immunocompromised patients as well as patients with retinal involvement should be referred to a retinal specialist.

Many of our patients’ concerns regarding the eyelid skin and the ocular adnexa can be addressed in the office. However, in cases of suspected malignancy or when patients are not responding to the appropriate treatment, a consultation with an oculoplastic specialist or dermatologist may be indicated.

Dr. Demeritt is a graduate of Nova Southeastern University College of Optometry. He currently serves the College of Optometry at Nova Southeastern University as an assistant professor. He is involved in clinical teaching at The Eye Care Institute.

Dr. Lewandowska is a graduate of The Ohio State University College of Optometry. She currently serves the College of Optometry at Nova Southeastern University as an assistant professor. She is involved in both, clinical and didactic teaching.

1. Sun, MT, Huang S, Huilgol SC, et al. Eyelid lesions in general practice. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48(8):509-14. 2. Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Shivakumar C, et al. Etiology and antibacterial susceptibility pattern of community-acquired bacterial ocular infections in a tertiary eye care hospital in South India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58(6):497-507. 3. Wald ER. Periorbital and orbital infections. Infect Dis Clin Am. 2007;21(2):393-408. 4. Bessette M. Hordeolum and stye in emergency medicine. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/798940-overview. Accessed January 10, 2020. 5. Dahl A. Sty (Stye). WebMD. www.emedicinehealth.com/sty/article_em.htm. Accessed January10, 2020. 6. Driver PJ, Lemp MA. Meibomian gland dysfunction. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;40(5):343-67. 7. Scobee RG. The role of the meibomian glands in recurrent conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1942;25:184-92. 8. Roodyn L. Staphylococcal infections in general practice. Br Med J. 1954;2(4900):1322-5. 9. Ozdal PC, Codere F, Callejo S, et al. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of chalazion. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(2):135-8. 10. Wali UK, Al-Mujaini A. Sebaceous gland carcinoma of the eyelid. Oman jJ Ophthalmol. 2010;3(3):117-21. 11. Leung AKC, Barankin B, Hon KLE. Molluscum contagiosum: an update. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2017;11(1):22-31. 12. Gerlero P, Hernandez-Martin A. Update on the treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109(5):408-15. 13. Basu S, Kumar A. Giant molluscum contagiosum – a clue to the diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2013;3(4):289-91. 14. Vora RV, Pilani AP, Kota RK. Extensive giant molluscum contagiosum in a HIV positive patient. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(11):Wd01-wd02. 15. Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. [Mollusca contagiosa in HIV infection. Clinical manifestation, relation to immune status and prognostic value in 39 patients]. Hautarzt. 1997;48(2):103-9. 16. Braue A, Ross G, Varigos G, et al. Epidemiology and impact of childhood molluscum contagiosum: a case series and critical review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(4):287-94. 17. Czelusta A, Yen-Moore A, Van der Straten M, et al. An overview of sexually transmitted diseases. Part III. Sexually transmitted diseases in HIV-infected patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(3):409-32. 18. Serin S, Oflaz A, Karabagli P, et al. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum lesions in two patients with unilateral chronic conjunctivitis. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2017;47:226-30. 19. Ray SS, Thomas A. Molluscum keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1974;22:31-2. 20. Schornack MM, Siemsen DW, Bradley EA. Ocular manifestations of molluscum contagiosum. Clin Exp Optom. 2006;89:390-3. 21. Berger EM, Orlow SJ, Patel RR, et al. Experience with molluscum contagiosum and associated inflammatory reactions in a pediatric dermatology practice: the bump that rashes. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(11):1257-64. 22. Osio A, Deslandes E, Saada V, et al. Clinical characteristics of molluscum contagiosum in children in a private dermatology practice in the greater Paris area, France: a prospective study in 661 patients. Dermatology. 2011;222(4):314-20. 23. Netchiporouk E, Cohen BA. Recognizing and managing eczematous lid reactions to molluscum contagiosum virus children. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e1072-5. 24. van der Wouden JC, Menke J, Gajadin S, et al. Intervention for cutaneous molluscum contagiosum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD004767. 25. Uter W, Schnuch A, Geier J, et al. Epidemiology of contact dermatitis. The information network of departments of dermatology (IVDK) in Germany. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8(1):36-40. 26. Saint-Mezard P, Rosieres A, Krasteva M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14(5):284-95. 27. Fehr BS, Takashima A, Matsue H, et al. Contact sensitization induces proliferation of heterogeneous populations of hapten-specific T cells. Exp Dermatol. 1994;3(4):189-97. 28. Ayala F, Fabbrocini G, Bacchilega R, et al. Eyelid dermatitis: an evaluation of 447 patients. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:69-74. 29. Rudloe TF, Harper MB, Prabhu SP, et al. Acute periorbital infections: who needs emergent imaging? Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e719-26. 30. Botting AM, McIntosh D, Mahadevan M. Paediatric pre- and post-septal peri-orbital infections are different diseases. A retrospective review of 262 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(3):377-83. 31. Baring DE, Hilmi OJ. An evidence based review of periorbital cellulitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36:57-64. 32. Jain A, Rubin PA. Orbital cellulitis in children. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2001;41:71-86. 33. Lee S, Yen MT. Management of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2011;25(1):21-9. 34. Jackson K, Baker SR. Clinical implications of orbital cellulitis. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:568-74. 35. Liu IT, Kao SC, Wang AG, et al. Preseptal and orbital cellulitis: a 10-year review of hospitalized patients. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69:415-22. 36. Howe L, Jones NS. Guidelines for the management of periorbital cellulitis/abscess. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29(6):725-8. 37. Kloek CE, Rubin PA. Role of inflammation in orbital cellulitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006;46(2)57-68. 38. Yang LP, Keam SJ. Spotlight on retapamulin in impetigo and other uncomplicated superficial skin infections. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(6):411-3. 39. Spoendlin J, Voegel JJ, et al. A study on the epidemiology of rosacea in the U.K. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:598-605. 40. Vieira AC, Hofling-Lima AL, Mannis MJ. Ocular rosacea-a review. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2012;75:363-9. 41. Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the national rosacea society expert committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-7. 42. Oltz M, Check J. Rosacea and its ocular manifestations. Optometry. 2011;82:92-103. 43. Akpek EK, Merchant A, Pinar V, et al. Ocular rosacea: patient characteristics and follow-up. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1863-7. 44. Ghanem VC, Mehra N, Wong S, et al. The prevalence of ocular signs in acne rosacea: comparing patients from ophthalmology and dermatology clinics. Cornea. 2003;22:230-3. 45. Lazaridou E, Fotiadou C, Ziakas NG, et al. Clinical and laboratory study of ocular rosacea in northern Greece. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1428-31. 46. Ramamurthi S, Rahman MQ, Dutton GN, et al. Pathogenesis, clinical features and management of recurrent erosions. Eye (Lond). 2006;20:635-44. 47. Vieira AC, Mannis MJ. Ocular rosacea: common and commonly missed. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:S36-41. 48. Al Arfaj K, Al Zamil W. Spontaneous corneal perforation in ocular rosacea. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010;17:186-8. 49. Alvarenga LS, Mannis MJ. Ocular rosacea. Ocul Surf. 2005;3:41-58. 50. Schechter BA, Katz RS, Friedman LS. Efficacy of topical cyclosporine for the treatment of ocular rosacea. Adv Ther. 2009;26:651-9. 51. Pfeffer I, Borelli C, Zierhut M, et al. Treatment of ocular rosacea with 40 mg doxycycline in a slow release form. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:904-7. 52. Papageorgiou P, Clayton W, Norwood S, et al. Treatment of rosacea with intense pulsed light: significant improvement and long‐lasting results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(3):628-32. 53. Craig JP, Chen YH, Turnbull PR. Prospective trial of intense pulsed light for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(3):1965-70. 54. Vrcek I, Choudhury E, Durairaj V. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus: a review for the internist. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):21-6. 55. American Academy of Dermatology. What to look for: ABCDEs of melanoma. www.aad.org/diseases/skin-cancer/abcde-of-melanoma. Accessed January 21, 2020. 56. Colin J, Prisant O, Cochener B, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of valaciclovir and acyclovir for the treatment of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology, 2000;107(8):1507-11. 57. Tyring S, Engst R, Corriveau C, et al. Famciclovir for ophthalmic zoster: a randomised aciclovir controlled study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(5):576-81. |